Nesting in the Wires: On Mário de Andrade’s “Macunaíma”

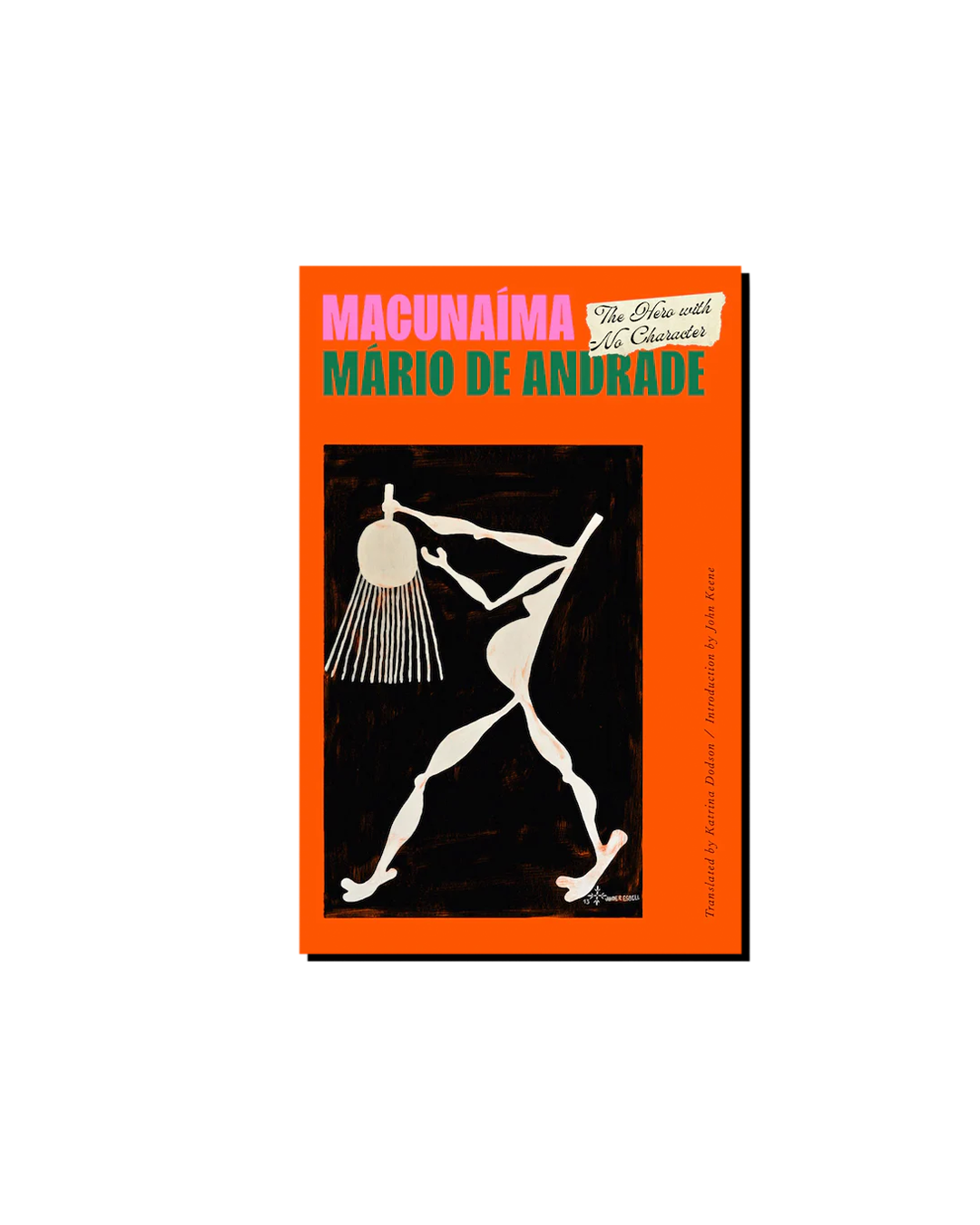

Mário de Andrade, transl. Katrina Dodson | Macunaíma: The Hero with No Character | New Directions | April 2023 | 224 Pages

Mario de Andrade attempted four prefaces to Macunaíma and never published any of them. These prefaces stand in marked contrast to the amount of time it took Andrade to write Macunaíma, which the Brazilian modernist famously composed in six days while vacationing “in the midst of mangos pineapples and cicada” at his uncle’s country house outside São Paulo. Andrade drafted Macunaíma in 1926 and, after a year and a half of revision, self-published it in 1928 with the subtitle The Hero With No Character. The subtitle bore two allusions: The first was that the book’s titular hero, a shape-shifting trickster figure lifted from Pemon mythology, lacked “moral reality” and this, in Andrade’s estimation, was reminiscent of his fellow Brazilians. The second was that Macunaíma had too much character—like Brazil itself, he represented a multitude of histories that deprived him, conversely, of a fixed, easily understandable identity. The paradox has shaped an understanding of the novel, and has pointed to a tension inherent in the book’s reception, even after its canonization as a masterpiece of Brazilian modernism, a tension that perhaps justifies Andrade’s frustrations with his front matter: Macunaíma’s provenance is a complex and nearly impossible task to summarize, yet the novel is often tasked, sometimes by Andrade himself, with the summary of a nation.

The information about Macunaíma’s composition, along with the prefaces, prefatory notes, letters, translator’s afterword, translator’s notes, and an introduction to the text all appear in Katrina Dodson’s new translation of the book, published this past spring by New Directions. In further contrast to Andrade’s six-day fit of composition, Dodson’s translation, the first she has published since winning the 2016 PEN Translation Prize for her translation of Clarice Lispector’s Complete Stories, is the result of more than five years of intensive research. Of the roughly 270 pages that make up this latest English-language edition, a third of them are devoted to supplemental text, a proportion that makes sense since Macunaíma itself is a text made up of other texts. Andrade based his Macunaíma on stories that had been collected and compiled by the German ethnologist Theodor Koch-Grünberg in a five-volume study of “Carib and Arawak peoples.” Andrade then modified and altered these stories by interspersing them with other Indigenous myths, particularly from the Tupi peoples and from Afro-Brazilian folklore, as well as other “songs, jokes, rhymes, sayings, and superstitions.” The result is a cross-reference of texts that reads, in Dodson’s words, like “an incredibly tangled game of telephone.” Koch-Grünberg, an Alan Lomax-like figure, wrote in German, basing his account off stories he had heard in Portuguese, which itself had been translated from Pemon. Andrade then wrote these texts back into Portuguese and interwove them with many others, all of which Dodson has now translated into English. The extended context in this new edition works to frame not just a contemporary English-language reader’s understanding of Macunaíma, but of how Andrade and Dodson’s texts both work through, and depend upon, translation.

Macunaíma’s plot reflects this mash-up. Andrade’s novel ostensibly centers the adventures and exploits of his hero with no character, who careens around Brazil with his brothers Jiguê, a dullard Macunaíma continuously cuckolds, and Maanape, a shaman, as he searches for his muiraquitã, an amulet given to him by Ci, Macunaíma’s deceased lover. Along the way Macunaíma tussles with his mortal enemy, the cannibalistic giant Piaimã, and runs away from a monstrous worm named Oibê. He dies several times only to find himself videogamed back to life. He attends a macumba ceremony, ends up in prison, witnesses several important events in Brazilian history, and, in one chapter, declares himself “Imperator” of São Paulo, writing a long, florid letter to the Icamiabas, otherwise known as the Amazons.

If this all sounds pretty loose, that’s because it is. Macunaíma is a shaggy dog, and Andrade’s delight in the sonic wordplay that rises from his hero’s excess and bawdiness takes precedence over a strict coherence. Events are held together by Andrade and Dodson’s linguistic gusto; in Dodson’s words, the plot has the feel of a Wile E. Coyote sketch, and there’s a definite thrill in seeing how long Andrade can keep the story running out over the ledge, sustained by a gust of wind. Comedy and violence intermix—Piaimã the giant ends up drowning in a vat of spaghetti; “IT NEEDS CHEESE!” are his last words—and, true to Andrade’s subtitle, Macunaíma’s portrayal ranges. He is part-myth and part-satire, mischievous, irresistible, lewd, and despicable; when he and Ci first meet, Macunaíma sexually assaults her, then moves blithely on. As if it were a later season of Game of Thrones, the novel disregards laws of time and space, unstitching and re-sewing Brazil’s map in the process. In one chase scene, Macunaíma and Piaimã shoot from the north to the south of the country in the space of a few sentences. Flora and fauna are also mixed about, a “deregonializing” of plant and animal that allows Andrade to posit Brazil, per one of his prefaces, “as a homogenous entity.”

While its muchness can make Macunaíma an exhilarating and confounding read, it makes sense considering the goal and scope of Andrade’s undertaking. Andrade does not simply borrow myths from different sources, but remixes and rewrites them in the process. A Pemon origin myth on the “three plagues of Brazil” is updated so that these plagues are now “coffee leaf critters, pink bollworms, and soccer.” An Afro-Brazilian folktale about the origin of the “three races of Brazil” is cleverly spliced with a Tupi-Guarani myth about a traveling missionary: Macunaíma, who is born “jet black,” jumps into an enchanted hollow of holy water, made by the missionary’s footprint, and turns white; Jiguê follows suit and turns the color of “new bronze,” but sloshes all the water out so that Maanape is only able to wet the palms of his hands and soles of his feet. Andrade is writing a hero and a book about the formation of national identity, yet Macunaíma also laughs and turns its tail at such a concept. Identity, just like consistency in plot, is constantly shifting and cast into question. “I copied everyone,” Andrade wrote in a 1931 letter to the writer Raimundo Moraes. “My name is on the cover of Macunaíma, and no one can take it off. But that’s the only reason that Macunaíma is mine.” Andrade’s methodology—part-incantation, part-appropriation, and part-inspiration—has opened the book up to criticism: What are the implications of employing histories sacred to Indigenous traditions in order to allegorize a national history? In its cobbling together of popular tales, is the novel depicting texts that work through stereotypes or does it veer into stereotype itself?

Given its range of vernaculars and lexicons, Macunaíma has long been regarded as a notoriously difficult book to translate. It is not just that the novel combines texts and languages, but that the novel’s significance nests in the wires of that combination. Different styles and registers of Portuguese exist alongside terms from Pemon, Tupi, and other Indigenous languages, which have to varying degrees been incorporated or not into Portuguese’s lexicon. Katrina Dodson’s immersion in Macunaíma, her more than five years of research that went into her translation, shines throughout.

If the act of translation is often reduced to a dichotomy of foreignization and domestication—that is, the preservation of unfamiliar or unglossed terms for a reader in translation vs. the smoothing over of such terms by rendering them in familiar language—Dodson’s work is not just a formidable example of both, but an interrogation, apropos of the book’s slippery relationship to the idea of national identity, of what constitutes the foreign and domestic in the first place. On the one hand, she preserves many terms in Portuguese, Pemon, and Tupi, in doing so requiring the English-language reader to maintain an awareness of the variety of sources in Andrade’s novel, and slowing the reading experience down so that this reader must move intentionally through the novel’s intertextual snarls.

At the same time, Dodson builds a sonic momentum and playfulness that speeds us through the text at the madcap pace Andrade encourages. She often achieves this, conversely, by “Americanizing” terms, cobbling and inventing “a literary pastiche” of American vernaculars and idioms that conjure the idiosyncrasies and particularities of the original. Macunaíma does not swig “rum” or “aguardiente” but “hooch”; his days are not “fortunate” but “lucky-duck.” Jiguê is not “witless” or “foolish” but a “big dummy.” Currency is referred to not as “reais” or its more archaic spelling of “réis” or even “dollars” but “greenbacks gravy marbles moolah dough vouchers peanuts frogs smackeroos, and the like.”

Dodson employs domestication not to smooth things over, but to provide a juxtaposition that further conveys—indeed, furthers—Andrade’s original project. In doing so, she unstitches and resews the maps of North and South America, just as Andrade does Brazil’s, implicitly asking the American reader to consider their own myths of national identity and formation. As she puts it, “After all, everyone is American in the New World.”