The End of White Innocence: On Eula Biss' "Notes From No Man's Land"

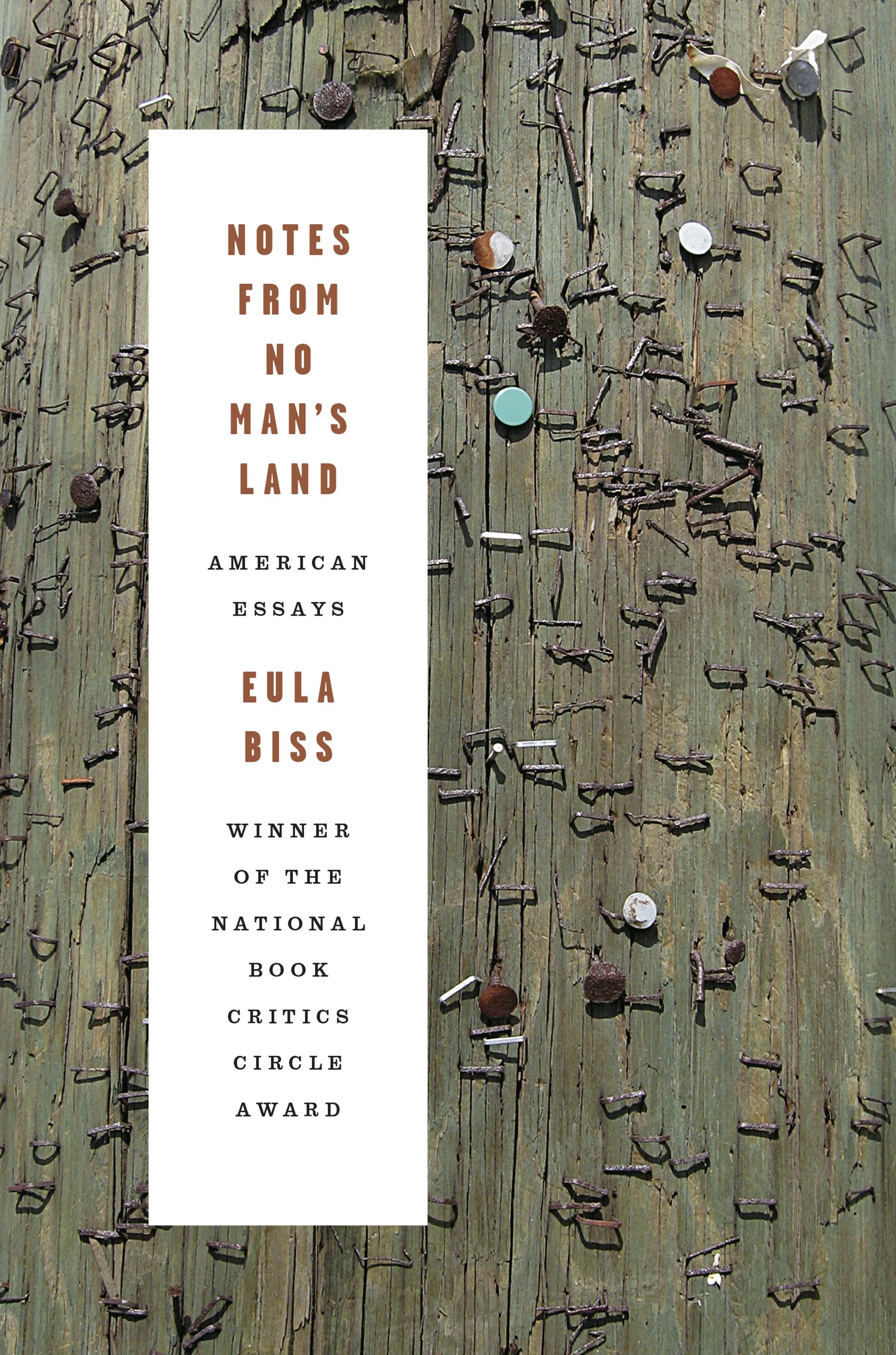

Eula Biss | Notes From No Man’s Land | Graywolf Press | November 6, 2018 | 256 Pages

The first essay in Eula Biss’s reissued essay collection Notes from No Man’s Land, “Time and Distance Overcome,” begins as a history of the telephone, then moves to focus specifically on telephone poles. At the end of the fourth page, Biss narrows her focus once more, this time to describe a series of lynchings that used telephone poles as their instruments. Only now has she arrived at the essay’s central concern. In the “Notes” section at the end of Notes, Biss offers an explanation for her seemingly roundabout entry into her theme:

“I began my research for this essay by searching for every instance of the phrase “telephone pole” in the New York Times from 1880 to 1920, which resulted in 370 articles. I was planning to write an essay about telephone poles and telephones, not lynchings, but after reading an article headlined “Colored Scoundrel Lynched,” and then another headlined “Mississippi Negro Lynched,” and then another headlined “Texas Negro Lynched,” I searched for every instance of the word “lynched” in the New York Times from 1880 to 1920, which resulted in 2,354 articles.”

Through this note, Biss confesses that she discovered the topic more or less by accident, and that to find her way into it, she had to change her patterns of attention. The structure of the essay, the slow introduction of the lynchings, involves the reader in a similar shift in perception. Through this rhetorical move and others like it, Biss invites readers to change their own patterns of attention with regards to race, as she has changed hers. In the last paragraphs of “Time and Distance Overcome,” Biss writes that her own grandfather raised telephone poles, and reflects, “When I was young, I believed that the arc and swoop of telephone wires along the roadways was beautiful. I believed that the telephone poles, with their transformers catching the evening sun, were glorious”. In the present: “Now, I tell my sister, these poles, these wires, do not look the same to me. Nothing is innocent, my sister reminds me. But nothing, I would like to think, remains unrepentant”. Here, Biss, bringing her white family into the narrative of telephone poles and lynchings, figures what can be seen as the primary movements of the collection: deconstructing white innocence, and replacing it with a sense of complicity in the racial violence that characterizes the United States.

“What exactly it means to be white seems to elude no one as fully as it eludes those of us who are white,” writes Biss in the second essay, “Relations”. Similarly deployed “us” pronouns recur throughout the collection, making it clear that Biss imagines her audience to be primarily her fellow white Americans. Several passages read as elegant “Race 101” lessons, such as “There is no biological basis for what we call race, meaning that most human variation occurs within individual ‘races’ rather than between them. Race is a social fiction. But it is also, for now at least, a social fact”. I am not white, and I have a degree in ethnic studies. I do not need introductory lessons on race, and have not needed them since I was a small child in Indiana, elucidating what it meant to be white by observing what surrounded and sometimes suffocated me. I do consider how I, too, have been implicated in antiblack violence, as an Asian American who benefits from racist systems in this country. Still, I wonder what it’s like to read Biss as a white person. I lack the ability, I suppose, to fully imagine white innocence. How effectively does Biss encourage her audience to unlearn it?

Notes from No Man’s Land was first published in February 2009, and as with any reissued text, it is important to consider what has changed in the intervening decade between editions. Most obvious is the change in the White House: two weeks before Notes was first published, Barack Obama, the first black president of the United States, was inaugurated for the first time; the release date for the reissue is Election Day two years into the term of Donald Trump, whom Ta-Nehisi Coates termed “The First White President.” Since Notes was first published, white nationalist groups have seen a resurgence; over forty people were injured, and one was killed, in the violence perpetrated by participants in the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville in August 2017. Have the stakes for deconstructing whiteness been raised, in light of these changes?

Biss paraphrases Toni Morrison’s observation “that the literature of this country is full of images of impenetrable, inarticulate whiteness”. She writes, “It isn’t easy to accept a slaveholder and an Indian killer as a grandfather, and it isn’t easy to accept the legacy of whiteness as an identity. It is an identity that carries the burden of history without fostering a true understanding of the painfulness and the costs of complicity. That’s why so many of us try to pretend that to be white is merely to be raceless”. Perhaps some white people still continue to pretend to be raceless these days. But whiteness now clearly has proud and sinister faces that call explicitly for the systematic dehumanization and destruction of people of color. Does this precipitate a death to white innocence? In 2018, whiteness is articulate; but perhaps it remains impenetrable, in need of deconstruction.

A March 2017 interview with Biss compares a passage at the end of “Black News,” in which she observes that reporters covering the masses of people marooned in the Superdome following Hurricane Katrina kept saying, “This doesn’t seem like America,” with similar rhetoric following the election of Donald Trump. In “Black News,” she quotes Kanye West saying, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people”; recently, West hugged the president while wearing a Make America Great Again hat. West remains in the reissue of Notes; Trump appears nowhere in the book, only haunting in the form of its re-publication’s context. The sole addition to Notes from original edition to reissue is a six-page coda, “Murder Mystery,” which includes the names Michael Brown, Laquan McDonald, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, and Samuel Dubose, as well as that of Emmett Till. Biss describes their deaths as “a long litany of lynchings,” and suggests that though the instruments may be the hands of police officers rather than telephone poles, violence against black men in the United States is just as present, just as pressing today as in the early 20th century.

The names of a few of the many murdered men have been added to Notes, but oddly, the words “Black Lives Matter” have not. A pattern of elision recurs throughout the collection, benign in some places—“I could check out any time I liked, as the song goes, but I could never leave” for some reason seeks to anonymize “Hotel California”—and more suspect in others—Biss declines to name “the first scholar of the subject” of lynching within the text of “Time and Distance Overcome,” displacing the name “James E. Cutler” to the Notes. I especially found myself wondering why James Baldwin was named nowhere in the text of or the notes to “Nobody Knows Your Name,” which appeared to me to be in dialogue with Baldwin’s essay “Nobody Knows My Name.” In the decade between editions of Notes, Baldwin’s legacy has received additional attention, with new critical studies and an Oscar-nominated documentary film devoted to him. Baldwin appears elsewhere in Notes, most prominently in the Notes to “All Apologies,” so it is clear that Biss has been reading his work. I could not come up with a satisfactory explanation for his omission in this context. Details in Notes are occasionally elided, perhaps in service of the smooth flow of Biss’s prose, but in many places, I wish they had been included.

Biss’s style does, however, inspire great admiration, not just in the flow of her sentences, but also in the structure of the collection at large. Though nearly all the essays in Notes were previously published independently, the collection’s greatest power lies in its coherence. The sections, “Before,” “New York,” “California,” “The Midwest,” and “After” signpost the geographical and temporary journey that is Biss’s engagement with whiteness. The last essay, “All Apologies,” moves into an alternative, equally implicating rhetorical strategy: the apology. Having already established white guilt and complicity in racism—for example, “We are afraid, my husband suggests, because we have guilty consciences. We secretly suspect that we might have more than we deserve. We know that white folks have reaped some ill-gotten gains in this country”—Biss moves to make the guilt actionable, offering a simultaneously personal and political history of white apologies and non-apologies. “Reagan signed legislation officially apologizing for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II;” Clinton did not apologize for slavery. Clinton never apologized to Paula Jones; Biss apologizes for breaking a flowerpot in Mexico. Attached to the anecdote about breaking the flowerpot is one of the most important observations in the collection: “An apology is incomplete until it is accepted”. Biss pivots from this immediately to, “If I apologized for slavery, would you accept?” The address here has shifted, from the “us” that refers to white readers, to a “you” that is black. The second-to-last-sentence in “All Apologies” is “I apologize for slavery;” this apology, generally addressed, cannot have been accepted. In “All Apologies,” apology breeds more apology. The first essay implicates white readers in racial violence; the last carries them along in an attempt to absolve white guilt, and intentionally fails. Notes from No Man’s Land is incredible precisely because it is incomplete.

The project of deconstructing American whiteness is similarly incomplete. Eula Biss attempts to apologize for the deeds of her people, but I wonder, for example, what it would be like to live in a world in which white men regularly apologized, even for the things they have done themselves. What kind of conversation would we have had if Brett Kavanaugh had apologized to Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, or if anyone at all (besides Joe Biden, decades later) had apologized to Anita Hill? Biss’s incomplete apologies are only a beginning to the many incomplete apologies marginalized people deserve. What will it be like to read this collection in another ten years, or twenty? How will forms of whiteness have changed in the interim? I cannot say, and nor could Biss, I think. What we can count on, however, is an insight she uses to bookend Notes. “Even now it is an impossible idea, that we are all connected, all of us,” she writes at the beginning of “Time and Distance Overcome;” at the end of “Murder Mystery,” she writes “What is obscured by the term identity politics is the reality that we’re all living out the politics of our time together”. I am neither the white audience to Notes, nor the black addressee of its concluding apology. Yet I, like all Americans, am interconnected, entangled with the politics of all of it.