“Crashes happen when a person gets hit by remembering”: On Brielle Brilliant's "The Spud"

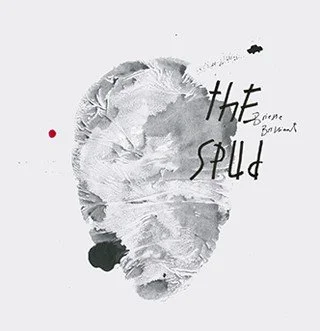

Brielle Brilliant | The Spud | Featherproof Books | November 6, 2018 | 128 Pages

“Crashes happen when a person gets hit by remembering”, a character thinks (or “decides”), while waiting in his truck, eating doritos, watching his brother cross the parking lot, in the opening sentence of Brielle Brilliant’s new flash-fiction novel The Spud. The brother being watched is revealed in glimpses and shards of memory to be the perpetrator of a shooting at a bakery somewhere in Idaho, an event that both makes up the black center of the novel and haunts its peripheries like a leaked gas. But memory is no simple thing in Spud. Nor is time, event, or location. The shooting is referred to both in future tense and in past tense, both in mathematically precise terms (“at 10:44am on the morning of the attack, anthony paxton is stopped at a traffic light 0.3 miles outside of the bakery”) as well as through idiosyncratic details noticed by random witnesses (“he was eating a hard-boiled egg”). Yet despite both the precision and supply of details, the reality of the event remains hard to pin down. Part of this has to do with the fleetness of the writing, which zips between inner memory and outer world with such speed that the boundary between the two begins to melt away. But another aspect involves the way Brilliant plays with the idea of location.

A few pages along, a tenth-grade girl, jd, holds up or “steals” kp—the brother of the shooter—by gunpoint, and proceeds to ride shotgun in his truck as he delivers packages across the region for work. The two eat junk food, remember anthony, (the shooter) and microscopically muse on death, relativity, perception, family, and high school through fifty some-odd fragments, passages of flash-fiction, poems, or cut up and re-spliced strips of film, depending on one’s interest in such categories. The title of each of these fragments is a location, ranging from private place names (“Rico’s”, “Pendl’s”) to specific addresses (“231 S. Hwy 33”) to certain interstates and highways (“Idaho State Highway 15”). Meanwhile, these fragments are broken up by small dialogues that are titled with five-digit numbers (“83422”, “83274”)—ostensibly certain zip codes of Southeast Idaho, but, deployed repetitively so as to call to mind emergency dispatch codes spoken over walkie-talkie, delivery confirmation numbers, and other oblique, impersonal sequences. These regular, site-specific references do little to tether kp and jd’s rovings to their purported zones and locations. Instead, the intermixed events and memories of the novel feel as though they are happening everywhere at once, blowing past the reader like splinters of exploded debris in slow-motion. Time-terms are swapped with space-terms. Inner processes collide with outer ones, so that to read The Spud is to find yourself at the center of a constellation of possibilities rather facing down a single hard, cool reality.

This welding together of specificity and obscurity give the fragments the aura of encountered objects rather than deliberately written pieces. One fragment struck me as being scratched into the dirt of a parking lot the characters pull into, while another—no longer than a few lines long—struck me as being scribbled onto a gum wrapper and left behind on a bar top for an anonymous drinker to consider before letting it dissolve into the surrounding whiskey labels, mirrors, tv screens, snippets of dialogue, and half-formed memories of a dusky highway tavern. There’s a certain thrill to this kind of encounter, words and thoughts not exactly meant for you, as happened upon at a bar, or glanced at on a television screen, or overheard in a gas-station restroom. And yet such words can never be assimilated into any neat narrative without losing the alien sheen that makes them attractive in the first place. Brilliant is masterful at conjuring this experience, playing and tinkering with the point at which narrative breaks down into naked, exposed words without ever letting them dissolve into chaos. The private memories of kp and jd are almost too private to make sense of, as though the camera is trained in too close on a piece of exposed skin or a blemish on a part of the body that can’t quite be made out. It’s disorienting, as sense of place is as swiftly and regularly interchanged as sense of time. But this sense of thrill and disorientation are part and parcel with the nature of the event that makes up the novel’s center as well as the mediums of perception through which that event is seen. Further contributing to this destabilization is the fact that The Spud is spherical rather than linear, with no obvious entry or exit points. Each reader will journey through it differently, finding in it their own entry and exit points.

This is not to say that The Spud is patternless: Brilliant casts and recasts certain words in different roles throughout—“crash”, “box”, “steal”—such that an encounter with any one of these words becomes a portal to its instance elsewhere, with the two instances rubbing different meanings out of each other. Yet play reigns. One last barely-describable impression I received while reading The Spud: that Brilliant was playing the children’s game of “Jacks” with the words and revisited moments of her novel, arranging, re-throwing, and swiftly catching unexpected correspondences and intersections between them mid-air.

What do such games have to do with the nature of a traumatic event? What can be said about such an event and what cannot? Does the event have a precise location and precise time? Or is it scattered like shrapnel into the consciousnesses of those that survive it? Or is it just something that exists on a screen, in phone audio, projected onto a wall, or reflected in a glass window? The Spud isn’t concerned with answers; instead it turns the reader into an investigator, bent over a memo pad, scribbling their own notes as they work to piece together the questions it sprawls on them. In this way, it’s the best kind of creative stimulant, a packed, potent, and challenging heir to experiments as devised by Lydia Davis, Valeria Luiselli, or the Roberto Bolano of Antwerp.

As the two drive along Southeast Idaho’s highways and interstates, making deliveries, there is a filmic mechanism at play such that what one person remembers or thinks, the other watches; private memories become public, bleeding out onto passing fast food signs, laptop screens, and the vast blank whiteness of a drive-in movie theatre wall. In “231 S Hwy 33”, we get the following sequence:

“kp’s watching another spud scene in the driver’s seat, listening to jd tell a story about her coach (jesse) bringing a pistol to soccer practice so they’d run extra fast. it wasn’t loaded, but jesse said it was, which is why kp’s rewinding to the parking lot, looking at jesse’s smile. it’s a smile kp never noticed until now, sitting in his car with this teenager and her gun. only corner teeth in the smile, the beginning of a spitting or a gargle.”

In these sentences we are simultaneously with kp as he listens to and rewinds jd’s story, with jd as she tells her story, and finally also inside that story—at the “soccer practice” watching the coach wave his pistol in the air. This is The Spud’s modus operandi, keeping plates spinning on several axes of reality at once. Yet despite all of the displacements of time and narrative and place, something important and simple happens: jd and kp talk to one another. This simple fact is the tiny miracle of the novel. There is no grieving in “Spud”, nor an ounce of sentimentality, but something nevertheless human emerges in jd’s approaching kd, kd’s quiet acceptance of her presence, and the two characters’ ability to exchange discreet words with one another.

Think of the event last August at Sea-Tac airport in Washington State, when a 29-year old employee “hijacked” an airplane from the tarmac, and, with no one else onboard, and with no flight experience aside from that copped from “video games”, flew the plane over Puget Sound for more than an hour, doing drunken-looking loops in the sky as he quipped with air-traffic control. “Hey do you think if I land this successfully, Alaska will give me a job as a pilot?” he asks at one point. Watching grainy you-tube footage of the event, the lone plane doing its sad loops of abandon in the sunset before crash-landing on an island (“I wasn’t really planning on landing it”), I felt mingling with my more socialized responses a kind of manic, alien, sympathetic glee. I was reminded of the phenomena by which some people laugh uncontrollably at the news of the death of a loved one, but I’m not sure this was the same experience. What was it? What’s a sane response to tragedy, personal or impersonal? As it travels back and forth along the highway extending from memory to live event to 280p video document, The Spud only multiplies such questions, reaching out in a way both bizarre and human to those willing to think creatively about what it means to respond to a crash.

This review is part of our Contemporary Literature series, where we review books that traditionally gain traction outside of the midwest in order to bridge the intellectual gap between Cleveland, the Midwest, and the coasts, and create an arena in which all three can be in conversation with each other on equal footing.