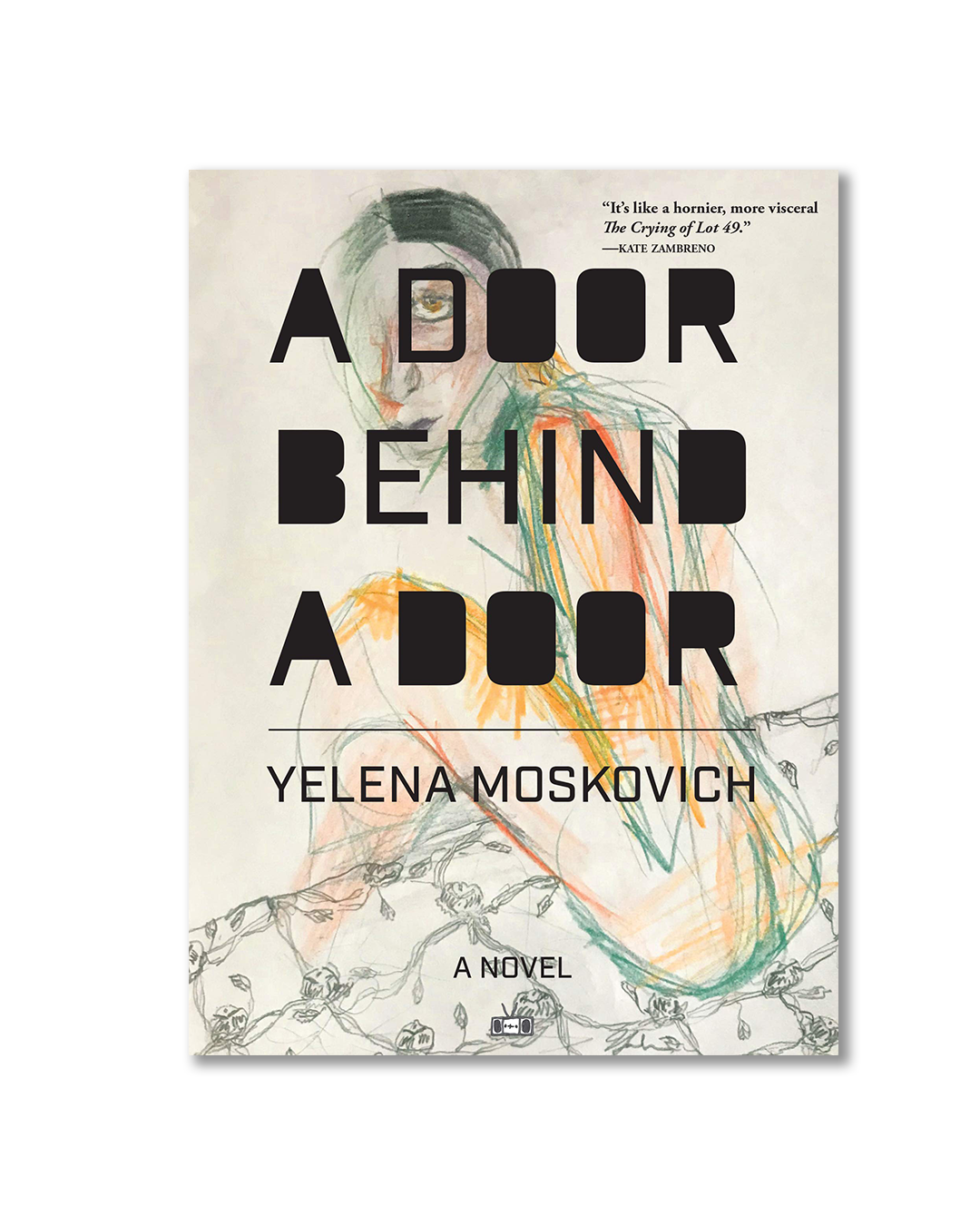

An Air Bubble Between Continents: On Yelena Moskovich's "A Door Behind A Door"

Yelena Moskovich | A Door Behind A Door | Two Dollar Radio | 2021 | 188 Pages

Olga Bokuchava left behind a traumatic childhood in the Soviet Union (along with the suspicious, rhythmic stabbing of a neighbor “once, twice, thrice”) and immigrated to Milwaukee with her family, from whom she then became mysteriously estranged. Now attempting to settle down with her comparatively well-adjusted American girlfriend, an ominous phone call from her past throws her world into a tailspin. This is the entirety of what we know concretely of the plot in A Door Behind A Door, published this past May by Two Dollar Radio—all else is up for debate and interpretation. If this setup suggests a linear mystery to be slowly unraveled and rounded off with a tidy conclusion, the novel defiantly undermines that expectation. Moskovich's book elides every tenet of narrative structure, falling just shy of inscrutability. In trying to piece together the broad trajectory of the novel, I turn to the memorable titular line:

“To get to Hell,” he says in a low voice, “they take you through America. There is a door behind a door.” (11)

This foreboding whisper seems to establish the nebulous gist of the text: essentially, we wind our way through Wisconsin, gradually sliding into the afterworld (or something that resembles it). The novel lingers in tenuous scenes of Midwestern familiarity—a 24-hour diner on the outskirts of Milwaukee, or a lesbian bar on the East Side—which are violently punctuated by interjections reflecting the sometimes bleak reality of immigrant existence in an all-American town. In one section, Olga has a conversation at a diner on 79th and Capitol while enjoying hot, perfectly melted American grilled cheeses, only for this episode to be immediately followed by the memory of suburban Wisconsin bullies severely injuring her younger brother’s eye in a parking lot. Jerked back and forth between flashes of feebly warm and bitterly harsh memories, we begin to discern a viscerally precarious image of the USSR transplant’s life in the Midwest as a frustrating experience of comfort and stability always just out of reach. We float between these immigrant scenes and glimpses of her Russian childhood akin to “an air bubble between continents” (16).

Moskovich’s background in theater and screenwriting conspicuously shapes the formatting of the novel, with headers and emboldened phrases mimicking scene breaks and dialogue. In an interview following the publication of her previous novel, Moskovich describes theater as “a false space, a space for communal belief and disbelief,” and reveals that “spatial language: ways to tell stories through movement, dynamics, incantation, sensual narrative... are all things that I take with me into prose.” The summoning of theatrical movement into prose fiction comes through more tangibly and successfully in A Door Behind A Door than perhaps any other work I have encountered. Moskovich’s theatrical background is evidenced not only in her formatting decisions, but also in the enunciated cadences that develop throughout the text. Wildly dancing from one page to the next, Moskovich’s style not only resembles a play, it also arrests the reader as witness and spectator to Olga’s world being flayed open in much the way we might watch a dramatic scene on a stage. Different sections, some as short as a few words, are told from a plethora of unexpected perspectives (including those of an old dog, a shadow, and a knife). These inventive ways of plunging us into different details achieve a delicate balance of the interiority expected from psychological fiction with general atmospheric chaos.

There is a distinct relationship between the rebellious essence of Moskovich’s storytelling and the queerness of her characters. The most frantic episodes of the novel are those to do with female desire spilling out in all directions. At one point, we become privy to the internal, lusting monologue of Tanya (a teenage mallgoer) which progresses almost entirely along the lines of:

Sometimes she makes me so wet. Sometimes my math homework makes me so wet. Sometimes the fucking sun rising on a new fucking day makes me so wet. What’s a teenage cunt to do? (82)

Flares of this sex-driven thought pattern continue, propelling the episode, pushing us to the chapter’s climax: an act of tragic violence. The idiosyncratic build-up of the chapter, the teen-girl cravings which too often go unspoken in literature, and the defiant representations of sexual development are manifestations of Moskovich’s deviation from convention on every level.

At times, Moskovich leans all the way into the abstruse nature of the text. One page simply reads “I am a lone.” The opposite page repeats “sailboat” echoing thirteen times in a column down the middle. I could attempt to interpret this, reading it as commentary on the futility of belonging, or an illustration of the loneliness that comes with familial estrangement, but doing so might taint the pure mystification of being stopped in your tracks while trying to follow a plot and forced to wonder: what does it mean to be a lone sailboat in Milwaukee?

We reach the end of this rollercoaster-ride novel and land on the final page:

The apartment is so quiet, it’s no longer an apartment.

The interval is so full, it’s no longer an interval.

The sea is so wide, it’s no longer the sea. (173)

This lyrical refrain encapsulates a prominent theme of the novel: we are always trying to hold onto things that are never what they seem. Leaning so much into something that we find ourselves lost in it is a singularly disorienting realization. Sara Ahmed, in Queer Phenomenology, describes “lostness” as opposed to linear “straightness,” defining her term as “a way of inhabiting space by registering what is not familiar: being lost can in its turn become a familiar feeling” (7).

To read A Door Behind A Door is to become familiar with inhabiting what is perhaps more an anarchy of words than a novel, and thereby to explore a “lost” register of one’s mind. Untangling myself from the book upon finishing it, head spinning and heart racing, I found myself in that state of mind, questioning whether the narrative I was trying to grasp was a narrative at all. The plot is muddy, the boundaries between life and death and past and future nonexistent, and Wisconsin might be purgatory on the road to hell. The jagged, disorienting sharpness of the work, like the rhythmically stabbing knife in the novel, is an invitation to collapse into it.