Reading Wo Chan in Ohio: On “Togetherness”

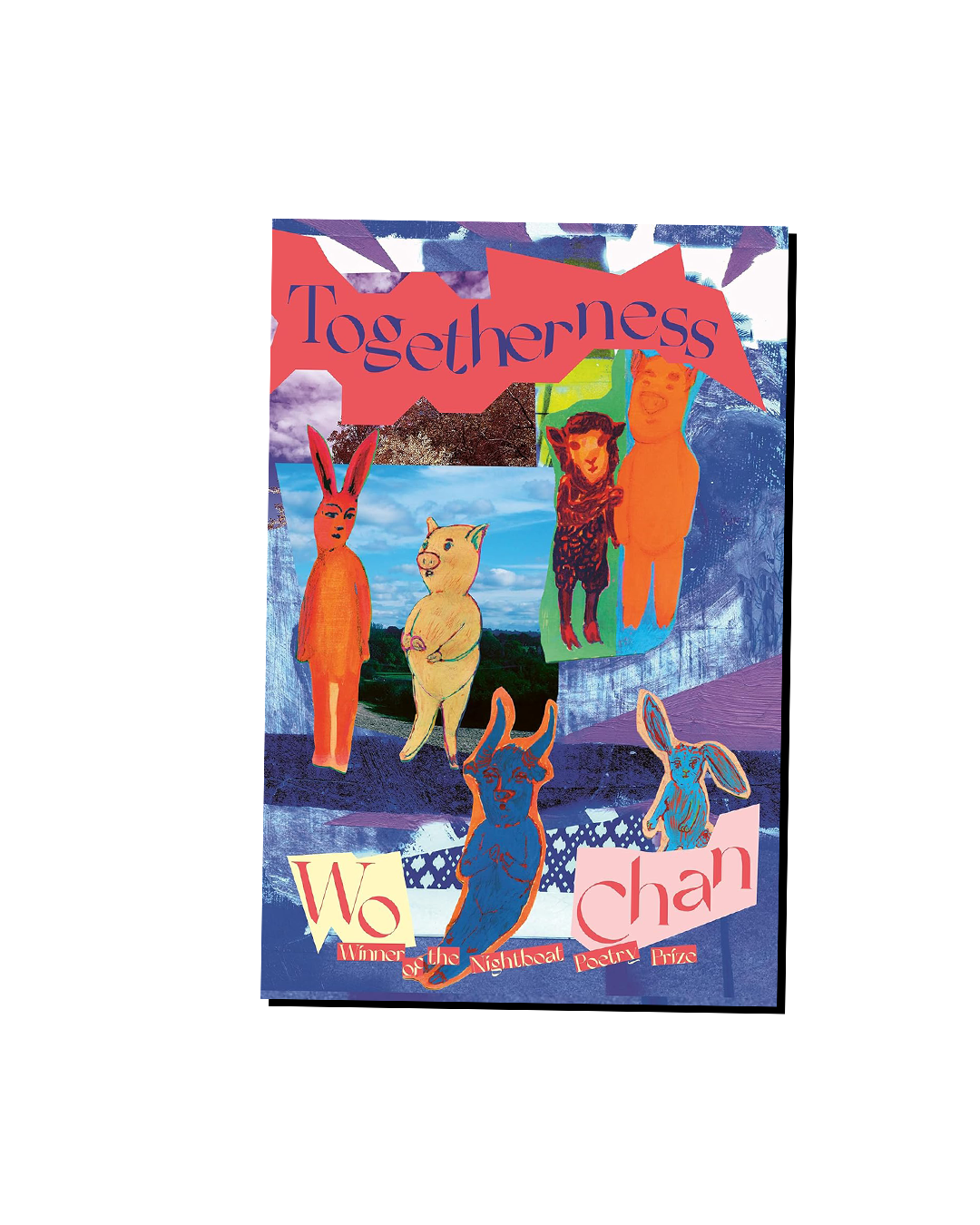

Wo Chan | TOGETHERNESS | Nightboat Books | September 2022 | 88 Pages

The bar was packed on Friday night. Over twenty performers had signed up. In the mirror-lined closet that functioned as our dressing room, we adjusted our tights and zipped up our pink vinyl boots. “Anyone got wig glue?” yelled a queen with buckles around her chest.

“I have lash glue,” I offered, still new to the backstage jostling and camaraderie.

She laughed. “Honey, that is not going to work.” Still, she adjusted my towering wig when I needed help.

No one could tell me why tonight was special; why, on a Friday in early February, the weekly open stage night (which usually drew a small but enthusiastic dozen onlookers and a handful of performers) was packed to the gills and glittering with all manner of scales. I learned that amateur performers had driven across state lines, from West Virginia and Indiana, to this small gay bar with a nondescript brick exterior in a quiet Columbus neighborhood. The outside hardly revealed the revelry inside: the exuberant students and the older gay men with long white beards; the witches and the enbies; the longtime regulars and the supportive straight friends; even an entire birthday party, cake and all, in one corner. And then there was me, fully sober and speechlessly euphoric, sweating under my high-as-heaven wig and thick new hip pads wondering what made this all possible.

•

“What makes you possible?” asks the drag performer and poet Wo Chan in their debut collection, TOGETHERNESS. It’s a question they ask multiple times in queer epistolary prose poems, written (perhaps, to a younger self) with the tenderness of a speaker recalling the memories that made them: adolescence in their parents’ Chinese restaurant in Virginia, “your first apartment in New York,” sex and love, and the TV show Chopped. The direct address creates a distance, allowing the speaker to conjure a separate self towards which they write. (And what is the past if not a performance, a posture we construct in the fleeting now?) At the same time, Wo’s “you” creates a closeness, inviting the reader to inhabit the space of the addressee, “the child of the restaurant, steeped in sodium and stir-fry.” I recognize these gestures from the stage, from the movement that happens in a drag performance between familiarity and strangeness, persona and identification. Other poetry undoubtedly achieves this effect, but Wo’s is a drag poetics, intentionally unearthing all the unexamined bits of personhood, nature, and language itself in a sizzling burst of sequins.

I was lucky enough to meet Wo at a conference two years ago, where they read from their forthcoming collection: poems about doing drag at the Whitney Museum, their family’s deportation battle, queer friendship and the power of art. I remember being instantly swept into Wo’s syntax and cadence: sentences that overflowed their lines, nouns adorned with adjectives, a lovingness and adoration, even for the violent world. Months later, the book arrived in the mail, and I brought it with me that weekend to a queer wedding in Springfield, Ohio. TOGETHERNESS in hand, I wandered around the small downtown, with intricate, art-deco buildings long abandoned and a repurposed train station which ceased service in 1971. In the small-town hotel overrun with a Chrsitian convention -- matching T-shirts with airbrushed crosses like an evangelical Lisa Frank -- I hid in the carpeted buffet room and devoured Wo’s poetry. Over the lobby, an enormous Blue Lives Matter Flag slowly waved.

Wo’s speaker is familiar with the violence of proximity. They write, “where can you harmlessly place your devotion? for what faint idea of a dream would you lift a flag?” Togetherness is not an innocent idea. Wo knows the harm that bodies can do to one another; their poems speak of war, interpersonal racism, deportation. A series of poems traces the speaker’s family’s deportation battle through the letters of community members writing on their behalf, attesting to the Chan family’s value as community members, business owners, parents, and hard-working Americans. As a guest on the Gender Reveal podcast, Wo explains how they crafted these poems from real letters, that the language is that of their neighbors and friends.

But even in this documentary poetics there is performance at play. One letter writer, a family friend who works in local government, emphasizes that “the Chans have contributed significant local tax revenues to the City.” Dressed up in the language of bureaucracy, of capital investment and productivity, the poem enacts and strips back the performances that America cruelly demands of subjects in its dehumanizing play of borders and citizenship. Behind humor, irony, and the genuine care of neighbors and friends, there is the persistent question: what does it mean to audition for a country that will not have you?

•

In July, Ohio Republicans introduced House Bill 245, joining a dozen other states pursuing anti-drag legislation. Under the guise of protecting children, the bill would criminalize certain public drag performances and earn the performer a felony if the performance was considered “obscene.” Meanwhile, drag performers are facing increased extrajudicial harassment in Ohio. In December, a holiday-themed drag queen storytime organized at the First Unitarian Church of Columbus was canceled last-minute after a planned disruption by Ohio’s Proud Boys and other right-wing groups. That spring, members of a neo-Nazi organization protested outside of a drag brunch fundraiser at a brewery in downtown Columbus.

I woke up that morning to live videos of the protestors, men wearing dark masks and swastikas and brandishing guns. From all accounts it was a beautiful day in the heart of Columbus; on the outdoor patio drag queens spun and lip-synced, raising money for a local LGBTQ+ youth organization. Over the stoic chanting of the men, the drag queens blasted their music, arms outstretched in defiance. The queens kept on performing, their pounds of makeup and hairspray struggling to hold in broad daylight. Nevertheless, it was the silent neo-Nazis who looked silly, ridiculous even.

I wanted to join the queens. I wanted to pull on thigh-high boots, armor myself in bright crimson lipstick and thick eyelashes, to channel my rage into something beautiful and triumphant. I was also scared of the hordes of armed men that would trespass into a place that was supposed to be ours.

What can beauty do for us in the face of ongoing violence? When extremist groups and State laws impose harm on queer and trans bodies, where do we turn? In their opening poem, “performing miss america at bushwig 2018, then chilling,” Wo describes the euphoria of a performance. Under an explosion of glitter and petals the speaker rolls on stage, where feet become dolphins, scattered pearls become “seeds from a seagull’s asshole,” and “joy was flapping its wings in the dustbath!” In the scene of the drag show, everything is lit up and hazy, transfigured, and for a brief moment “we ditch our brains unable to shred the fog of futures where civics, passion, paycheck, and pleasure meet.” Better futures not only seem possible, they feel alive and present in this moment of performance, and in Wo’s poetry.

Still, I am skeptical of beauty. “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” writes Keats in his oft-quoted “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” These are hotly debated lines, sometimes taken to justify the intrinsic and immortal value of art. In her book, Keat’s Odes: A Lover’s Discourse, Romantic scholar Anahid Nersessian reads the line ironically. Concluding a poem that depicts scenes of sexual violence, the final lines of the poem belong to a speaker who wants to see “the aesthetic appeal of the urn cleanse and redeem the horror it depicts.” The urn is beautiful, and its beauty flattens the difference between hypothetical and real harm, such that the speaker knows only to praise it. Here, beauty is an end in and of itself, uncritical, a tool, according to Nersessian, to maintain and legitimize Western civilization.

But Wo is no Romantic, and the beauty they evoke is subversive. Wo’s poetry is closer to the surreal of Federico García Lorca, tripping through New York, “bumping into my own face, different each day.” Influenced by Dalí, Lorca paints a world of strange and ecstatic imagery, where “crystalized fish were dying inside tree trunks” and “swarms of windows riddled one of the night’s thighs.” The Chicago Surrealist Group described surrealism as “a revolutionary movement. Its basic aim is to lessen and eventually to completely resolve the contradiction between everyday life and our wildest dreams.” Lorca, although he did not explicitly associate with an artistic movement like the surrealists, is interested in this contradiction. “I am made of impossible love,” he writes.

I think of the radical love experienced in the moment of Wo’s performance, the vision of an impossible future made momentary present. For Lorca, feelings are physical, like “pomegranate-colored violence” or “the ivy of a shiver,” lines that would feel at home in TOGETHERNESS. For Wo, too, beauty is not an end. Fantastic language is never flowery for its own sake but necessary, the materiality of queer life. At the end of a long night of performance, Wo writes, “i just wanted to sit and melt / like kerrygold into your fur coat. you said it was real. i knew that. i felt it.”

Does it matter whether the coat is “real” animal fur? Drag employs fantasy to create something real. Through a wild amalgamation of props, costumes, makeup, lighting, sound, and gesture, the performer evokes humor, delight, disgust, grief, rage, heartbreak—a feeling made possible through connection with the audience. Wo reminds us that a thing doesn’t have to be tangible to be felt. The magic of a performance, and a poem, cannot be taken back, or stolen, or legislated, or hurt.

•

In the poorly lit bar I fastened long, sharp nails to my fingers. I squeezed into a furry yellow bodysuit over layers of tights and foam padding. I began to recognize the new limits of my assembled body: an ass suddenly bumping into chairs, hair doubling the width and height of my head. In my new form I became both elegant and gigantic, lithe and towering. I recognized the power I imagine the queens felt twirling defiantly in front of that line of neo-Nazis.

Wo argues that poetic form is drag. A sonnet is a gown; a sestina a catsuit. Each form a different silhouette, a posture, a character, a move getting us closer to some kind of truth. To better approach one another. Wo considers themself “a form nerd.” I get that, in the possibilities of trying on new styles, new maneuvers, and discovering what can be made. When the State tries to limit the kinds of bodies that can exist in public, as Ohio has in January with some of the most draconian anti-trans legislation in the country, I understand it is afraid of drag queens: there is liberation in being shown the multiplicity of ways a body can be. When we question the boundaries of gender, what other borders might we reject?

In one of the final poems of the collection, Wo enacts a spinning, breathless performance on the page. “Tender Buffet” tells the story of working at the family restaurant in a remarkable burst of memory, four pages long with only two periods, and every lavish detail of the food, customers, and environs the speaker can muster. Wo praises the buffet table, “Oh! big friendly giant, billowing hull of nymphic dreams,” and the cornucopia of dishes it holds, “a bloviation of steel shredded cabbage,” Crab Rangoon like “golden footballs,” sweet and sour sauce “redder than the Earth’s principal bolts of lava.” Each tercet leaps into the next, and in a swirl of smells and sounds Wo compresses an entire season into a few breaths. In the last line of the poem, after describing the speaker’s own reflected face and the faces of their parents and siblings, Wo writes, “all this I glimpsed and still no words.” It’s delightfully ironic; four pages and still “no words”. Indeed, TOGETHERNESS teaches us that the project of living is absurdly serious and seriously absurd, and what could be more silly than attempting to approximate life through language, to touch what touches us with words? Still, against the cold, limiting language of state violence, Wo’s lavish adjectives and astonishing similes, their exuberant syntax and assonant lines touch the world with care, with love. “Tender Buffet” is an abundance of, indeed, tenderness, and yet, in this final line Wo insists queerly, militantly, tenderly, for more and more and more.

•

That cold February in that unassuming bar, I lip-synced to “You Don’t Own Me” by Lesley Gore (who was queer, I learned, miraculously, after the fact, stumbling around on Wikipedia). I was a kind of sexy Pikachu, rejecting Ash’s attempts to put me in a ball. I pouted. I shook my monstrous head. I beamed, mouthing, “I’m free, and I love to be free.” The crowd roared. Although I was completely sober, I can’t quite recall everything that happened on stage. I know I bent to blow a kiss to a friend. I know that at some point the audience shouted back, “You don’t own me!” I know that like Wo Chan, “i want some epic use for my excellent enjambed body,” and that in the pages of TOGETHERNESS, as in the bustling drag bar, I get some hint, some glimpse of what that might be.