Freedom and Space: In Conversation with New Yorker Cartoonist Will McPhail

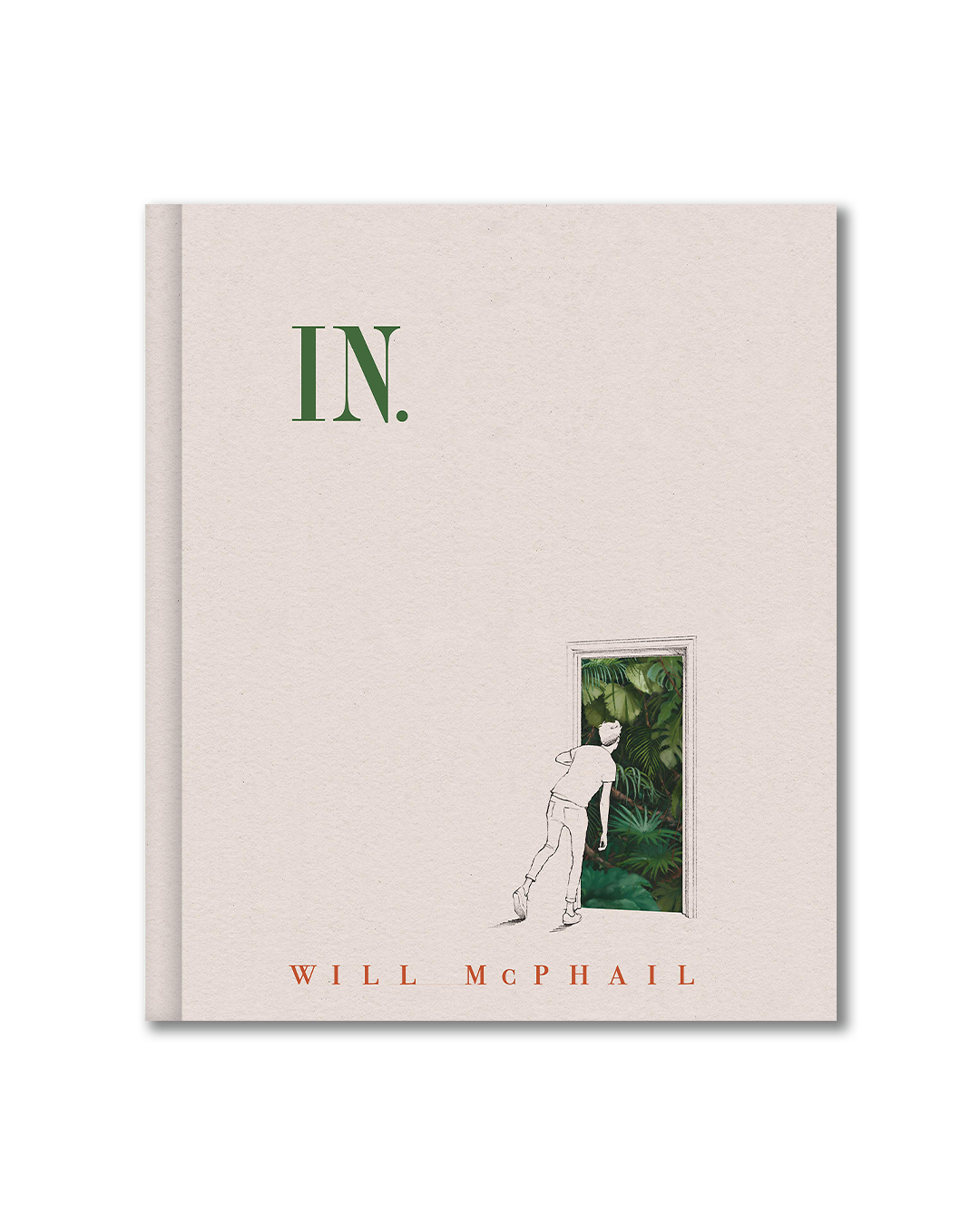

Will McPhail | In: A Graphic Novel | Mariner Books | 2021 | 272 Pages

New Yorker cartoons are recognizable on sight: simple black-and-white sketches of a scene captioned with some drollery that gently mocks the upper echelons of liberal society. But the cartoonists behind these wry inventions each have their signatures, from Bob Mankoff’s besuited characters, shaded in with hatching and dots, to Emily Flake’s softly-colored-in, baggy-clothed hipsters.

Will McPhail, who has been contributing cartoons and humor pieces to the magazine for the last seven years, has cultivated a delightfully manic style which favors themes of loneliness and social performance (one couple ascends the stairs toward a house party: “Just be myself? Fine, I’ll go cry in the shower”). He has a tendency to satirize the high-end coffee shops he likes to frequent (“Small, medium, or that,” says a barista, while a handful of patrons lap up coffee from a trough) and to anthropomorphize animals like birds and rats (McPhail finds inspiration for these characters from his formal training as a zoologist, as well as the pigeons that frequent the windows of his flat in Edinburgh, Scotland). His characters have simple but wildly expressive eyes and a vivid, anxious humanness. (“Spice up your panic attack with a harmonica.”)

As warmth and humor pervade McPhail’s single-panel cartoons, so too do they fill the pages of his debut graphic novel, In., which is a deeply pleasurable literary and visual experience. A funny, dreamy slice-of-life narrative, In. follows Nick Moss, a young artist on a quest for social intimacy in a world of rote small talk and constant distraction. Slowly paced, visually minimalistic, thoughtful and quietly sad, reading In. often feels similar to watching an indie film or listening to an alternative singer-songwriter. (In the course of our conversation, McPhail admitted to the influence that Phoebe Bridgers’ recent album, Punisher, had on the book.)

At times, Nick butts up against a wall, meandering around the city from hipster coffee shop to hipster coffee shop, stuck in conversations that go nowhere. He meets Wren, a boisterous, spontaneous oncologist with whom he strikes up a fun but perhaps performative romance. As he opens himself up and attempts connection, he begins striking upon serendipity, and the pages flood with rich, vibrant color as we traipse into the surreal dreamscape of his interlocutors’ internal worlds. These moments of transcendence are powerful, beautiful, and at times unsettling, and through them we experience the complex worlds of memory, intimacy, and grief.

~

Lily Houston Smith: It's so funny—I was just rereading In this morning, and there's this one scene where Nick is clearing a space in his messy apartment for a video conference, so that his space looks organized and professional for the call. And I thought, oh no, I haven’t done anything like that at all.

Will McPhail: [Laughs.] Yes. I see you haven’t taken that liberty, Lily. I was just looking around and I can see open drawers, I can see hats on things. I love it. The book is all about being honest with each other, don’t forget.

LHS: That's true. And also about leaning into the awkwardness of social interaction, which I find is exacerbated by video calls like Zoom.

WM: It’s an absolute hellscape. Social cues are just completely non-existent.

LHS: Well regardless I’m very excited to talk about In., which I really enjoyed reading. And it’s also such a beautiful object to hold and flip through.

WM: Oh, thank you. Yeah, they did a really good job with it. And you've got the American version, right?

LHS: Yes.

WM: I prefer the American version.

LHS: What’s the difference between the two?

WM: To the untrained eye, they look exactly the same, but the British one’s got a quote on the front. I kicked up such a fuss about that, having a quote on the front. So they reduced it so that it just says “Brilliant.” And now it looks sarcastic—like it’s saying “brilliant” with an eye roll.

LHS: Up until now, you’ve made a career mostly doing cartoons for the New Yorker, where you just have this one little space that everything has to fit inside. So I’ll ask a question that you’ve probably heard before: what made you want to work on this longer, more contemplative piece?

WM: Nobody's asked me that question, actually. People have asked about how it felt different, but not why I wanted to do it. And I never really thought about that.

I guess I’d been doing the New Yorker cartoons for a little while, and I was starting to feel a little bit constrained by the single panel because with the New Yorker cartoons, you’ve got to fill the whole world into just a little square. You’ve got the premise, the setup, the punchline, the caption—this whole snapshot of the world in one tiny box. Whereas when I moved over to the graphic novel, it was all new to me. First of all, just the space alone—to literally have more space on the page for drawing—was really freeing. To be able to take things really slow. If there was a joke to be made, I didn't have to make it in a tiny little caption. I could make it slower—or not be funny at all.

But then, when the book was coming to an end, I was thinking about my New Yorker cartoons and I realized like, no, this is the freeing thing: I get to write about pigeons. Nothing matters at all! What I write doesn't have an effect on the story arc down the line, so I can do whatever I like. It can be jarring to go between the two, but it's just a different muscle. And now, I find that one is a relief from the other.

LHS: Another difference I imagine is just the amount of time it takes to create a cartoon, as opposed to the longer project of a graphic novel. How long did it take to write this?

WM: It took about a year and a half to finish. It was all written before the pandemic, but all of the coloring and the drawing I finished during our first lockdown in the UK, which was weird.

LHS: Especially because the book ended up being so much about isolation and face-to-face interaction, which of course are things we’ve all been thinking about more than usual over the last year and a half or so.

WM: Right. I would be lying if I said that the pandemic hadn't affected how I wrote about isolation—or how it made me relate to Nick. But to be honest, I've been a little reluctant to tie the two together, the book and the pandemic. I worry that it might feel a bit exploitative. I just don't want it to come across as like, You know that thing that killed your grandma? Yeah well, I wrote a book about it! Pre-order now!

I think the problem that everybody I know—all my friends—had was that when we were locked down and when the pandemic was at its worst, we all felt directionless. We're not going to our normal jobs and we had nowhere to point towards. Whereas I had this book that I had to finish. I had a deadline. So I think it was more the case that the book helped me with the pandemic as opposed to the other way around.

LHS: That makes so much sense to me. I think it feels obvious to tie the theme of isolation in the book to this extremely isolating situation, but these are issues that far predated the lockdowns.

WM: Totally. In fact, the book gets really sad towards the end, but more than the pandemic affecting that was Phoebe Bridgers’ album. Like that was just as influential to me. Her second album came out just when I was at the delivery-driver-knows-my-name stage of the pandemic, and that thing is such a sad, beautiful masterpiece, it affected this book just as much as the pandemic did.

LHS: Oh wow, totally. I have listened to that album more than one time in a row while just sitting and staring at a wall. And it’s so funny that you mention her, because I think, too, she’s an artist who’s interested in the same kind of simple honesty that In. is about.

WM: Exactly. That's totally true. I mean, she's really funny also. This is not me comparing myself to Phoebe Bridgers. But she wrote that whole album before the pandemic, but it came out during the pandemic and it seems so fitting. I think the pandemic just kind of let everybody key into this same emotion that a lot of us have felt at various periods throughout our lives.

LHS: Like you said, this book gets really sad, and I did get quite misty-eyed towards the end. But also like you said, it’s funny. And I found myself chuckling more than once. Like, for instance, your protagonist, Nick, is an artist who’s wandering from hipster coffee shop to hipster coffee shop. And you’ve created all of these various names for coffee shops like “Gentrificchiato” and “Exhausted Corduroy Coffee.” What inspired all of the coffee shop names? Is it possible that you have some amount of hostility toward hipster coffee shops?

WM: No, definitely not. I get quite a lot of questions about how autobiographical the book is, and I think that it's actually most autobiographical in the humor. There's a lot of humor that I feel comfortable using because it feels self-deprecating. So when I'm teasing those coffee shops, I feel like I’m teasing myself because I actually love them and go to them all the time. There are a few instances where that happens in the book. There’s a part where Wren teases Nick for being a “woke boy.” The only reason I felt comfortable doing that was because I am proudly what you would call a “woke boy.” And so it felt like I was teasing myself as opposed to mocking that idea.

LHS: This seems like a good time to ask: To what extent is this book autobiographical?

WM: It is all fiction I've informed with real life experiences—except the opening sequence. The book opens with the swimming pool bowl tube slide thing—that is my actual life. But the rest of it is fiction.

You know, I've lost people that I love, like everybody else, and I've had these conversations that feel transcendent in their intimacy and that feel like I’m exploring this person's world. But I've never connected with a plumber in my bathroom the way Nick does.

LHS: I would actually love to talk about the waterslide scene. It’s the first moment of many in the book where you just have people staring at each other with your trademark circular eyes. Those eyes almost defy explanation, they are so expressive.

WM: I’ve developed those eyes over time—and throughout my work with the New Yorker. I started off drawing when I was little, just ripping off Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson, and doing little dot eyes. Eventually they got bigger and bigger and bigger because I just loved how expressive I could be. I loved how tiny, minute little changes in where the eyebrow is, or where that underlid of the eye sits, can just convey a totally different emotion.

So that’s why there's so much of that in the book. There's about four lines of dialogue in the whole book and the rest is just brooding looks. Which, I should say, I’ve always been more comfortable expressing complex emotions visually, rather than verbally. And as I was going, I was taking out dialogue because my favorite work of other people’s is the stuff that trusts that the reader can interpret and work things out themselves—and gives the reader the space to think and decide things for themselves.

LHS: I’d love to talk about some of your characters. So there’s Nick, who is our main figure, who’s quite isolated and reserved. And then Wren, whom he meets and develops a relationship with, acts as a bit of a foil to him, because she’s so outgoing and forward and larger-than-life. But there’s a way in which she isolates herself, too, with her sarcasm and humor. I wonder to what extent you were thinking about how all of these characters—Nick and Wren, but also the mother and the sister—how they all isolate themselves in various ways.

WM: That's absolutely right. I kind of designed every character to have their own mechanism of obscuring their true selves. Nick has this tendency to observe rather than to participate. He's always seeing stuff from the outside looking in. His mom, Hannah, has allowed Nick to define her by her motherhood, as opposed to them being two, independent adults. And Wren, exactly like you say, has a way of hiding herself with her humor. Every time Nick tries to push the relationship emotionally and connect, she brushes him off with a joke or some bit. And although I think the most entertaining parts of the book are when that happens—when you’re seeing Wren be this joyful person—what you're actually seeing is her shutting Nick out. You're seeing her keeping him at arm’s length.

There's a part where Nick initially meets Wren. She’s been on a date with a different guy, and Nick asks how it was, and she says it was brilliant because they were completely incompatible. She's shutting people out with humor, and the breakthrough is her not doing that.

A lot of her character was based around family members I have who work in the NHS [National Health Service]. And almost all of them have this character trait where they can be incredibly serious and compassionate in a professional capacity. And then, like a light switch, they can turn it off and suddenly be their joyful selves again. It’s kind of jarring when you see it happen. That was another aspect that I tried to give to Wren’s character.

LHS: I can confirm that those parts of the book are very funny.

WM: Thank you. I was trying to make it clear—exactly like you said—that she has a way of shutting people out. But it was also important that you be entertained while you were waiting for those color sequences.

LHS: Right. And mixing humor in with those more serious, sadder moments has a really powerful effect. Without giving anything away for people who haven’t read the book, it’s not just about social interaction, it’s also about illness and loss. What made you want to bring that dimension into it?

WM: I didn't set out to. [Laughs.] I didn't mean to! It's the first time I've ever done anything like this, so I was really flying by the seat of my pants throughout the whole thing and just trying to let the story lead me where it felt natural. I had this idea about these connections that we can make and how there are these worlds within people that you can explore. And the next thought after that was, oh, one of the worlds is going to have to be loss. Once I knew that it was going there, the rest was just informed by my actual experiences with loss and grief.

LHS: What’s been the best part of this experience of writing In. and seeing it out in the world?

WM: It came out in the UK yesterday, so a bunch of people are reading it at the moment. And somebody told me that when they're having conversations with people now, they've started imagining what that person's world looks like—visually. And that's really, really lovely to hear.