When Technology Bleeds

We start with two parables from a technoculture in turmoil:

In California, new cybernetic creations birthed from the VC-backed wombs of Silicon Valley (GPT-4, LaMDA, Dall-E, and so on) exhibit qualities we had long assumed were solely ours. They write. They draw. They create. This unsettles us. Some of us ask whether this means they are truly alive. Once this question is spoken, it cannot be unspoken. A flood of doomsaying and hand-wringing descends upon us. Have we summoned God? The Devil?

In Maryland, a man is given the heart of a pig. The heart is genetically-modified to avoid rejection. The man lives for two months. Scientists hope that one day such organs will be fully human, albeit harvested from inside our porcine friends. No one denies these pigs are truly alive. They suffer. They think. Engineered machines are allowed to think as long as they bleed. We are carnivores, after all.

We find ourselves in a world populated by thinking code, pig organ printers, and all their strange ilk. The tightly policed borders of the “human” have crumbled to reveal the ruins of the “posthuman” desert, where the hybrid offspring of beasts, technics, and humans live among one another. We are deeply unprepared to confront this newfound condition. We lack the concepts necessary to navigate this terrain void of the landmarks that had guided our thought for eons. Our ready-made myths fall apart, those well-worn stories of human exceptionalism and technological dominance. The frightening truth is that there never was a solitary island of man distinct from the environment, no cogito separated neatly from a sea of dumb, inert objects. Rather there are only sacrilegious couplings—a constant flow of things coming together and falling apart. Microplastics invade the blood-brain barrier; technological apparatuses outsource our minds; universes of bacteria in our guts serve as a “second brain”; man ingrains himself into the rock strata and atmosphere. We begin only where we end.

We have little to show for ourselves. Our misguided faith in the cult of the human has left us alienated from the broader world. As the eco-theorist Tim Morton puts it, it’s only what we have been “doing to other species” that has enabled us to think of ourselves “as a species.” This false phantom finally dispelled, we confront the perilous twilight brought about by our imperious creation of the figure “man”—the Holocene extinction continues marching ever-onward towards oblivion.

All is not lost. From the rubble emerge all those subhuman, inhuman, and nonhuman creatures that had remained subjugated under our despotic rule. In these monstrous times, we need a monster to guide us through the shadowy territories that lie beyond the fallen borders of the human (“monsters,” after all, are descended from the Latin “monere”: to warn or advise). What sort of creature might prove capable of leading us through these uncertain times—of teaching us how to properly exist in this awfully entangled world of ours? This is no trivial matter. When worldmaking, “it matters what thoughts think thoughts,” as Donna Haraway reminds us. The concepts we use to make sense of the future play a role in bringing that future about, so we must be careful in choosing the foundation of our new myth.

•

Haraway published her Cyborg Manifesto in 1985. She put forth the now-iconic figure of the cyborg to stir the imagination, believing that it could help break down our phallogocentric creation myths and liberate us from the oppressive binaries that had so long structured Western thought. The image of the cyborg realized our increasing technological and animalian imbrications, the first to be truly born from posthuman lands. “The cyborg appears in myth precisely where the boundary between human and animal is transgressed,” she writes, the points at which the distinctions between “organisms and machines” collapse. Through this monster, Haraway found a “blasphemous” way of being-in-the-world, something that unsettled us by living in the accursed excluded middle, that didn’t require the conceptual wholeness of that Western patriarch “man.” It rejected the dualisms that had hollowed out the ground beneath us—self/other, culture/nature, man/woman—in an effort to restore us to terra firma, a more honest (and for this reason messier) state of relations to the world we inhabit.

The cyborg quickly caught on in popular culture, proving to be a potent lighting rod for all those anxieties that hovered above like overripe storm clouds. In the high Reagan era of the 1980s, Haraway’s prescient blasphemy was both enticing and frightening. On the one hand, it embodied those early techno-optimists’ hopes that our newfound cybernetic lives would prove democratizing and free us from constraining identities like gender and race while connecting us to a global community. It also helped articulate the fears that surrounded technological integration, brought to dreadful life through media like Paul Verhoeven’s corpo-fascist Robocop (1987) and villains like Star Trek’s Borg (1989). If this was indeed, as Baudrillard remarked, an era of cooling—cooling systems, cold wars, cold pleasure, cool promiscuity—then the cyborg, with its cool-to-the touch chrome plating, was tailor-made for this milieu, everything we hoped and feared to be.

Ultimately, the cyborg was appropriated by the technoculture it sought to critique and transformed into a predictable archetype subsumed by the binary logics it had been introduced to deconstruct. It is now precisely because of our cyborgian lives that we are so efficiently tracked, mined for data, sold as views and engagement, and swayed by algorithms. Companies would happily have us all live as cybernetic organisms as long as they get to own the architectures on which we exist and the data we produce. Meanwhile, the cyborg is little more than an aspirational punchline at the end of an ad for VR goggles and haptic gamesets.

Times changed. Hope in the deconstructive possibilities of digital life faded away as the internet transformed into a flaming garbage heap of corporations, neo-Nazis, and all their bedmates. Cultural theorist Seo-young Chu once asked whether the posthuman world would be a post-stereotype world, or stereotypes would simply look more posthuman. Years later, as internet denizens participate in virtual yellowface, AI tools mistake darker-skinned people for monkeys, and digitized influencers leverage their racial ambiguity to rake in millions, it seems we have our answer. Cyborgian caricatures litter our mediascape, neutered of their radical politics. Even Haraway herself later admitted that this idol proved to be an incomplete guide for the future to come, increasingly incapable of gathering “the threads needed for critical inquiry” after “Reagan’s Star Wars times of the mid-1980s.”

We need a new figure to carry on the project of the cyborg, to stir our imaginations and encourage blasphemous thought. I find myself returning to the image from our bloody second parable: a pig, birthed with the organs of a man, a “body without organs,” to misappropriate Deleuze and Guatarri (who themselves misappropriated the poet Antonin Artaud), whose innards are both its own and something wholly alien to it. A hot-blooded thing formed from an ever-hotter world. Part animal, part man, part machine. Entirely monstrous. It is at once contemporary and mythic, technological and biological. Tim Morton would call this a “hyperobject.” I prefer to call it by its scientific name: the chimera.

•

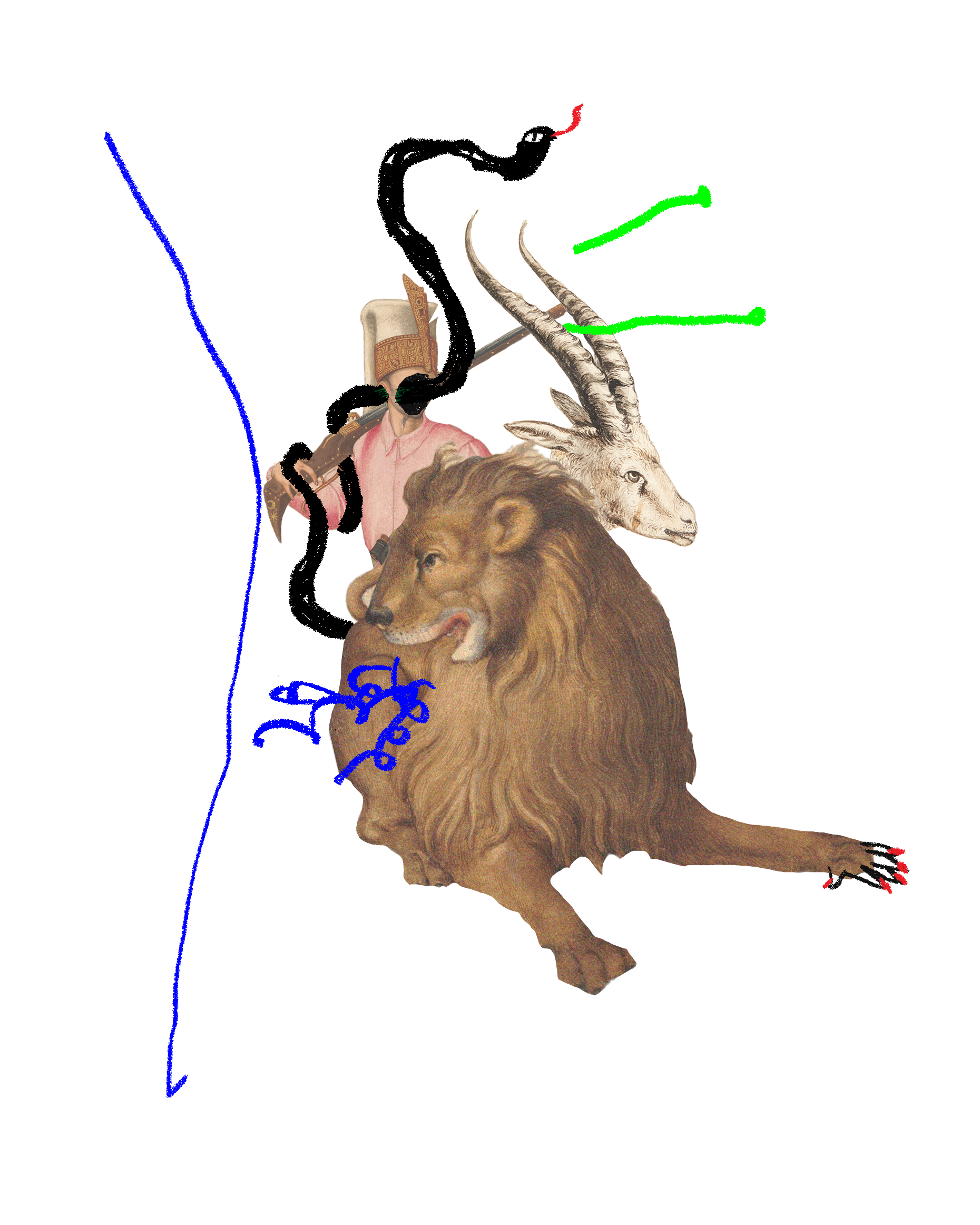

The chimera is a bestial revelation. Myth describes the monster as having the head of a lion, goat, and snake emerging from its body; modern science describes it as an organism composed of multiple genotypes. Perhaps more accurately, one can think of it as a mode of being—an existence that revels in its horrifying ambiguousness. Though they occur naturally, chimeras are also artificially induced. It is genetic code realizing digital code, “virtual” insofar as its deceptively simple appearance belies the complex processes necessary to bring it into being. It represents untold possibilities, unpredicted combinations, a web of uneasy, necessary relations.

The chimera is a close descendent of the cyborg, albeit one born of a warmer climate. The chimera tries to reintroduce the idea of fleshy, warm-blooded life back into a cold, “frictionless” technoculture discourse, collapsing physis and techne. It isn’t a sterile, regulated body powered by nuclear fission and covered in steel, but a cancerous thing that can easily spiral out of our control like a rogue mutated cell, a necessary reminder of just how little control we actually have. It traffics in blood and guts and slime as much as it does in lithium and silicone—biological mediums that we must center if we are to make sense of the ecological transformations and catastrophes surrounding us. Amidst the death of the green world, the chimera gives us a body with the pulse of many hearts to guide us.

Perversely, the chimera isn’t interested in “posthuman” discourse. To it, this notion continues to hold the residual reek of anthropocentrism. So much of the posthuman is mired in what happens to us when the human dissolves; how we are changed by our encounter with the nonhuman Other. Consider posthumanist art, from the interventionist pieces of Eduardo Kac (who made a bunny glow simply because he could) to the demiurgic stunts of Damien Hirst (who killed real animals to teach his human patrons a theoretical lesson about death). The art critic Carol Becker puts it thus:

In the universe of the posthuman it would appear that the human species will now not only fuse with machines to determine their destiny and how human they will become, but also, no longer the victim of nature ourselves, will become even more the choreographers, curators, and programmers of all other existent, and yet-to-be-imagined species.

The chimera has no patience for narratives like Becker’s wherein the world/human barrier dissolves because everything is absorbed in a violent conquest by homo sapiens (a critique Haraway has leveled against terms like the Anthropocene). Instead, the chimera points us backwards, toward a “pre-human” age swirling with abominations and possibilities. The chimera is the story of the mitochondria that embedded themselves into primordial prokaryotes to generate eukaryotic life. It is the story of our gut flora, where bacterial cells outnumber human cells 10:1 and contain over 100 times the amount of genomic content than the human genome. It is the story of those companion species that we’ve loved, abused, and altered at the level of genetics, as well as those viruses that continue to lodge themselves into our own DNA and too-porous bodies. It is the story of how we, as a unitary entity, never really were. The chimera isn’t a new creature birthed by our technoculture as much as it is an ancient being rediscovered through it: a full circle, “weird” in the sense of being a “twist or turn or loop.” It utters “ashes to ashes” with one breath while exhaling “resurrection” the next, reminding us that we are not just stardust but also viral leftovers, fecal biomes, vestigial organs, digital prosthesis, and much more.

Though the concept may still be in the early stages of gestation, we can sense it slowly taking shape at the peripheries. Artists, attuned as they are to the subtle changes in the atmosphere surrounding them, have already begun to take inspiration from this figure—if not in name then in principle. Take Wangechi Mutu, whose fantastical pieces explore densely entangled forms that bridge the gap between animal and human life in an effort to develop a “radically changed future informed by feminism, Afrofuturism, and interspecies symbiosis.” Or consider Agnieszka Kurant, Tomás Saraceno, and Sougwen Chung, who have based much of their artistic practices on collaborating with nonhuman agents—termites, spiders, and robots, respectively—shedding anthropic notions of “authorship” by opening up artmaking as a collaborative act. Not to mention all those ancient practices—from floating tree bridges to permaculture that never needed recourse to the distinctions between the artificial and natural in the first place. We have long sensed the gravitational pull of the chimera.

•

If humanist creation myths tell the story of how we rendered Nature obsolete through our own ingenuity, and posthuman creation myths extend this logic to create the conditions of our own obsolescence, then what story will our chimeric creation myth tell? Fables of imperialist conquest and Darwinian survival presume too much of us. Their endings are too predictably disastrous. Perilous times require us to chart an alternate history that begins long before homo sapiens, revealing not only how we came to be, but also what we owe to others. We need myths that re-enchant us with our mutual obligations, not fill our heads with noxious thoughts about what we deserve. A third parable, at the dawn of our technoculture.

In primordial seas, perhaps near hydrothermal vents, an assemblage of inanimate particles come together to form the first rudimentary organisms. From this seed blossoms a variety of life. Bacteria arise, as do protozoa. Some of these protozoa develop a peculiar feature known now as an anterior field: a “front” dedicated to interacting with the world (opposed to the radial symmetry of organisms like sponges, which lack a discrete front and a back). Suddenly, we become directional, and the possibility of Dasein emerges; we are oriented, we face a certain way. Over time, within this anterior field, sensory organs develop. Suddenly, the world comes into being as sensation. For some creatures, the organs for prehension and ingestion separate within this field. In addition to their given role in locomotion, limbs begin to aid the face in grasping and eating. The world appears to us as something manipulable. Then, at some point, bipedalism frees these hands to reshape the world around them. We find ourselves able to gesture, caress, and craft. The world becomes technical, expressive, unbounded with possibility.

This is the story of our chimeric beginnings told to us by the French anthropologist André Leroi-Gourhan in his work Gesture and Speech. Absent are the moments which typically litter our techno-histories: our control of fire, early tool use, the wheel. There is little room for such heroic inventions made by Great Men. Rather, we trace the arc of our technological becoming through our embodied legacies; our bipedal, directional bodies are both the medium and ur-technics that birth all crafts to come. We are little more than a protozoan mode of being that has sprouted many heads and appendages—a consecration of structures that happened to enable our particular form of technicity. Every technology is subject to this fleshy past.

It is a malleable history open to new modification and strange growths. It is also non-teleological; other modes of technics and being remain possible. After all, what else is a smartphone if not a new appendage, an extension of the anterior field that reunites our organs for prehension, sensation, and ingestion into a singular point as we swipe through the virtual world and absorb its detritus in one fell swoop? Unlike the tale of cyborgian intervention, the chimeric myth sees these electronic prosthesis as a humble addition to our carnivalesque panoply of inheritances. It adds to but does not override or negate that which we previously accrued. No matter how hard we try, we will never transcend our bodies nor render them obsolete through digitization.

We owe to others everything. We find traces of ourselves everywhere. In ourselves, we find traces of the Other. Our grandest marvels are built upon gradual accumulations. What poetry or philosophy could exist without direction? What direction could exist without the anterior field? Just as Heidegger observed that the essence of technology is not technological, we can observe that the essence of humanity is inhuman. We reunite with the chimeric pigs as kin. Their ruptured bodies and spliced DNA mirror our own, woven with the threads of alien life; so too does their exploitation, their reduction to standing bodily reserves. Foucault suspected as much when he spoke of biopower and the formation of the docile body. We are all so terribly intertwined. Their condition, their fate, is ours.

•

Amidst the metaphysical vacuum left by the simultaneous departures of animal, man, and machine, the chimera offers a figure through which we can pave an alternative path forward. Recognizing this figure is a political act that enables us to further deconstruct those oppressive ideologies that stem from the notion of the human as a unitary whole. The media theorist Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, for example, once noted how the human was historically created “through the jettisoning of the Asian/Asian American as robotic, as machine-like,” and the African American as “primitive, as too human.” In contrast to the human’s logic of negative exclusion, the chimera is additive. It recognizes that existence is always predicated on tenuous alliances. In doing so, it legitimizes all those bodies that were deemed lesser for their hybridity—vindicating them precisely because of this composite complexity.

Moreover, the chimera paves the way for a new form of eco-politics grounded not just in kinship, but in an ontology of mutual-dependence. Gaia is a chimeric entity, an attempt to take seriously the metaphysical implications of the vivacious relationships between organic and inorganic matter that sustain the planet. Likewise, an ecosystem is chimeric—an assemblage-creature that is increasingly being recognized in courts of law as a being that deserves legal standing. We are not just bound to each other out of choice or warm and fuzzy empathetic feeling; rather, existence necessitates it. There is no being outside of being-with, an idea with a long tradition in non-Western thought. Take, for example, the concept of ubuntu found in the philosophers of Southern Africa, which emphasizes the ways in which we only become a person through others.

In time, the chimera will likely be subsumed by the culture to come, defanged like the cyborg before it. Such is the fate of all heroes. But for now, let it unsettle us, let it confront us with the grotesque facticity of our existence. As we seek to bridge the gaps between chatbots, humanoid pigs, species jumping viruses, and planetwide systems, the chimera can serve as a fruitful guide that reminds us of the fundamental incoherence that lies at the heart of being, turning our attention away from gadgetry and innovation-centric hype that runs through so much of modern discourse and directing it towards the sinews and cartilage, bacteria and viruses, animals and beasts and subhuman things caught up in our technoculture. These are the “Chthonic ones” of Haraway’s Terrapolis, the meek destined to inherit the Earth. Following the chimera out of the dead soil of the human will be an unnerving experience. But that’s precisely how we’ll know we’re on the right path.