Graphic Scores: The Chapbooks of The Offending Adam

Ava Hofmann | My My Summer of Total Ffailure | The Offending Adam

Vivian Houle | Unsung Songs | The Offending Adam

Sarah Kortemeier | Aristotle’s Poetics | The Offending Adam

In terms of words that slice two ways, “graphic” is distinct. It’s category and quality. It refers both to content that is shown graphically (as in, visually) and to “graphic content,” which shows intensity. The core in either case is vividness, and a visual depiction might tip at any point toward intensity—the graphic becoming graphic—much as writing, under duress, might tip toward drawing, from script to scribble. That’s fitting, since the gentle homonym of “graphic” is twinned at its root: “graphikos” means both to write and draw, acts that became separate, in my early schooling, not in the holding of the pencil, and not in the forming of the letters, but in the connection of letters to sound, from the mountains of “m” to the mouth-feel of “mmmm.” But what sounds was I making when I was “just” drawing shapes? What shape should a sound make?

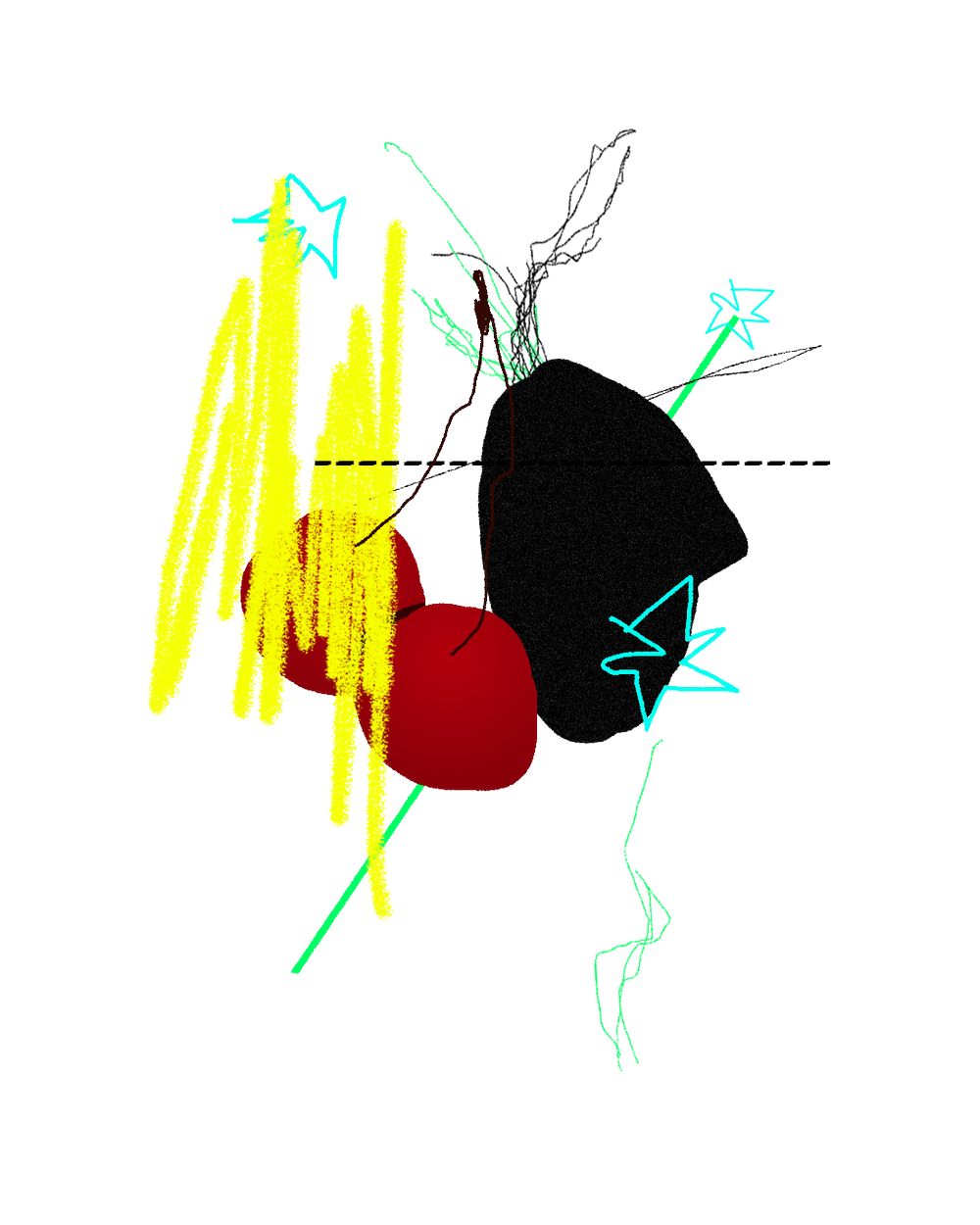

That question—of how to sing like a squiggle, how to crescendo an oval—is at the heart of graphic scores, those idiosyncratic systems of musical notation. With homonyms in mind, you might hear “score” cutting two ways: the graphic score foregrounds an impression, which scores the eye, scratching past retina to ear. Those systems may be systematic, such that a big triangle next to a dash means a major key, or more systemic and holistically indeterminate, inviting musicians to play a spiral as they see fit. (Check out Cornelius Cardew’s “Treatise,” performances of which are available online, and the scores from Brian Eno’s Music for Airports, among many other examples.) The visual and audio poems in Ava Hofmann’s My My Summer of Total Failure, a recent digital chapbook from The Offending Adam, engages with the tradition of the graphic score as well as with the dual meanings of “graphic”: Hofmann’s presents the “graphic” (as in, intense) via the “graphic” (as in, visually represented) in ways that keep the spectacular from becoming merely sensational. That’s partly a result of the visual form of most of the pieces, which recalls a three-panel comic strip. That frame is both sturdy and insufficient for the content, as in the first piece in the collection:

In the audio of the piece available at The Offending Adam, a flat bell clangs at intervals that are regular yet halting. There’s ambient crackling. The poem is performed left-to-right, without noticeable regard for the panel breaks; it runs through the gutters. Among the plain (but panged) delivery, “fragile” enters in a whisper, and “dead planet” is spoken in a voice that fits its font: half-heavy metal DJ, half-keyboard effect. Most of the non-lingual elements, such as the rubbery blur in the bottom left, aren’t rendered directly, although there’s a set of cat-like chirps at the end, corresponding to the array of jagged blossoms at the bottom right. The hush of “fragile” adds some metacommentary, folding through Hofmann’s language, which is already folding back on itself, even as it surges forward: “and there is something like like information stored,” Hofmann writes, and I feel held in the glitch of “like like.” Figurative language often clarifies meaning, but “like like” defies simile, emphasizing that, as Hofmann writes, “I don’t want you to understand what.”

As a result, the “what” I get—and which I get I’m, perhaps, not supposed to get fully—is “like the underside of an apartment: all.” That totality is one of understory, a foundation made sensual and candid and complete. The obliquity flies into a bracing image (“a clipped little wing”) and the arrow on the dashed line shoots me back, toward that nebulous, wobbly mass in the bottom left. I see that mass more distinctly because its representation is missing from the audio. Thus, the poem’s text and performance, for me, end up emphasizing a non-lingual graphic element, an effect that happens variously through Hofmann’s collection, with its fractured and frank engagement with queer identity and experience, health, and personhood among economic and political distress, “in a world where cherries existed and i got to eat them.”

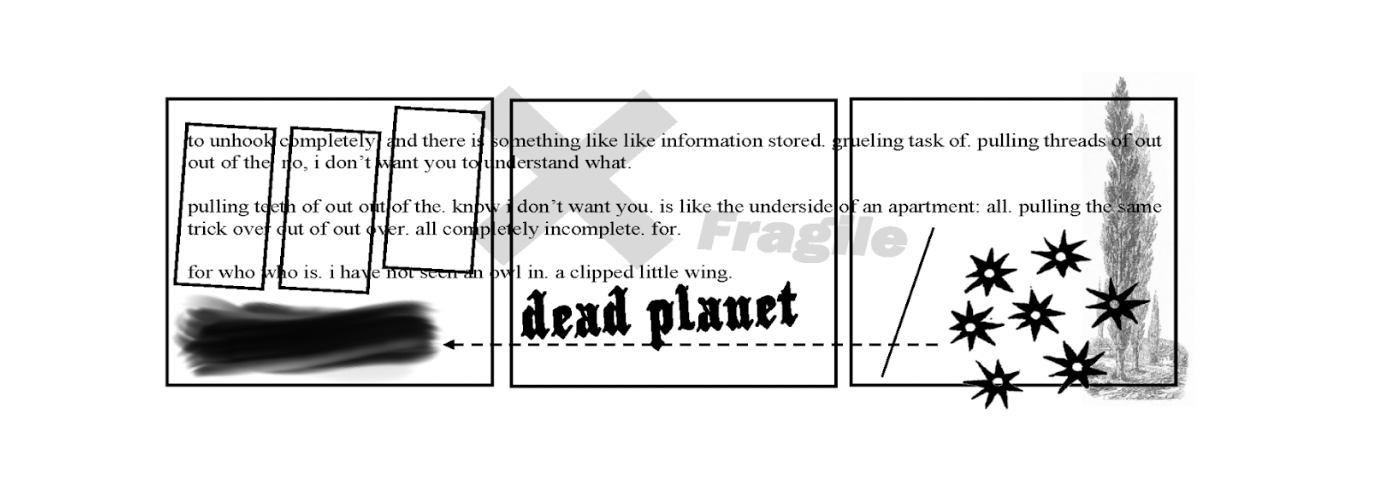

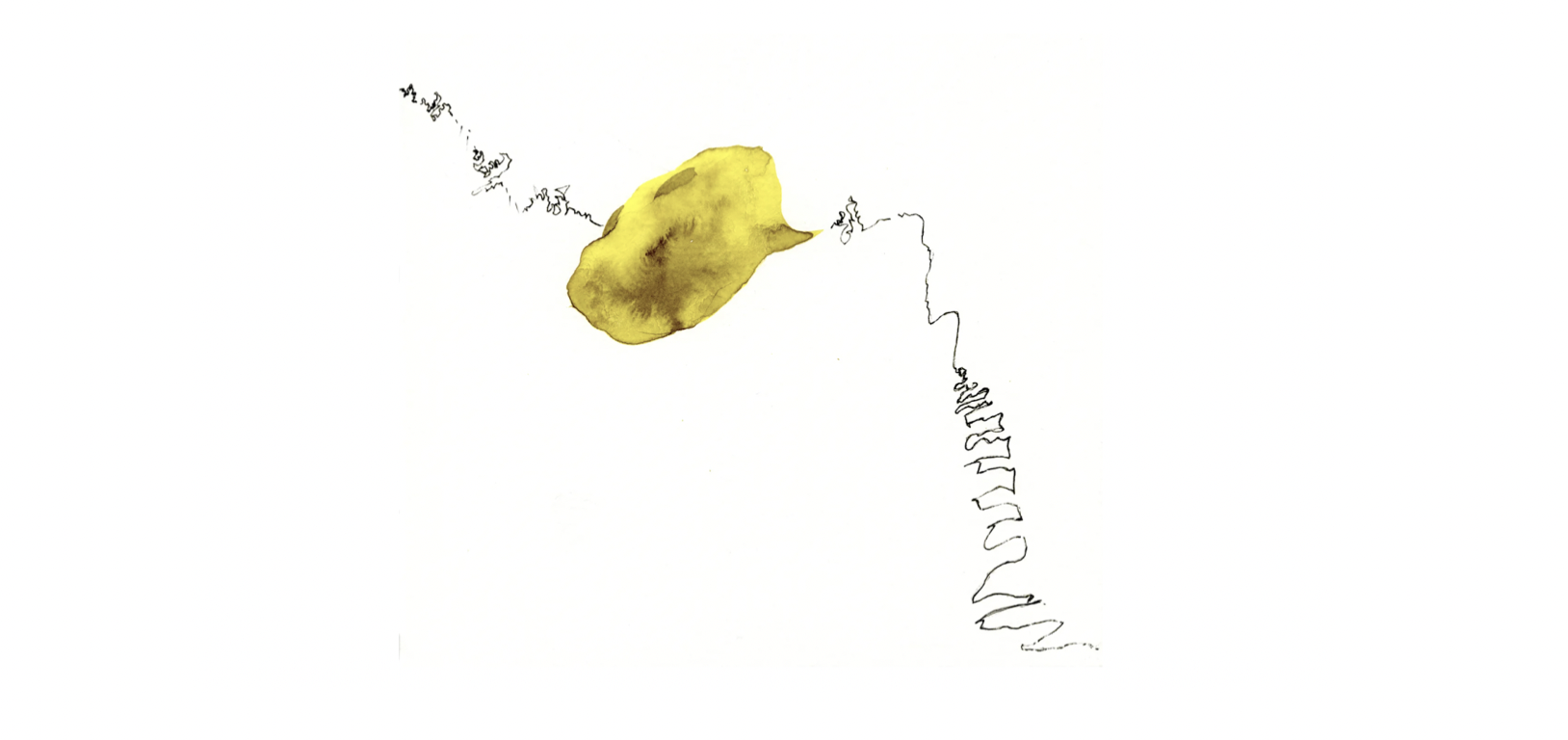

Readers may remember The Offending Adam from its earlier iteration, as an influential online journal. It’s back as a publisher of digital chapbooks such as Hofmann’s. Vivian Houle’s collection in the series, Unsung Songs, emphasizes the relationship between graphic scores and poetry more explicitly: Houle is also a composer and musician, who works with visual notation. The chapbook features a series of 34 of those pieces—from two-tone tangled strands to colorful puzzles of gears, often recalling the output of topological imaging systems from fanciful realms or the tracks and fossils of creatures who live there. 12 of the pieces include poems written “after” the musical scores. They’re by writers including Jeremy Allan Hawkins, Brett Evans, Melinda Wilson, and Sandra Simonds. As ekphrasis, these poems don’t just respond to visual art; they render it into language, into performance. They do this with varying degrees of directness. Hawkin’s poem, “a bright wave squelching between us,” for example, considers the relationship of an “us” between a “cloud” that is “temporarily expressed as a lake,” abstractly dramatizing the image:

Other pieces are more tangential. Sandra Simonds, for example, responds to an angled smear of crystalline, diagonal platelets with an account of a day “built of buzzing edges” and “untaggable” events:

and when I woke I made

coffee and looked across the century

I mean the yard where lawn debris

was piled high, will I get my kids to

the dentist today or was that

a goldfinch in the ditch’s red dirt—

potato chip potato chip

or will that cicada really outlive

my poodle?

The poem extends from the sequential, shifting consciousness that the score evokes. It “moves” like the score, we might say, which is interesting, since both text and score are technically still; the two stillnesses, together, emphasize a particular sense of animation. In Simonds’s poem, that motion leads to her receiving a text of “a photo of the Duino Castle.” It looks “pretty like fate or / something important.” The poem then leaps to enter “one of its 536 golden rooms,” and we see that the Castle is Rilke’s, and the poet’s, and that the graphic score may be a representation of that castle, or of the sense of it, in which the poet “tried to remember / the future and it came / out as an elegy.”

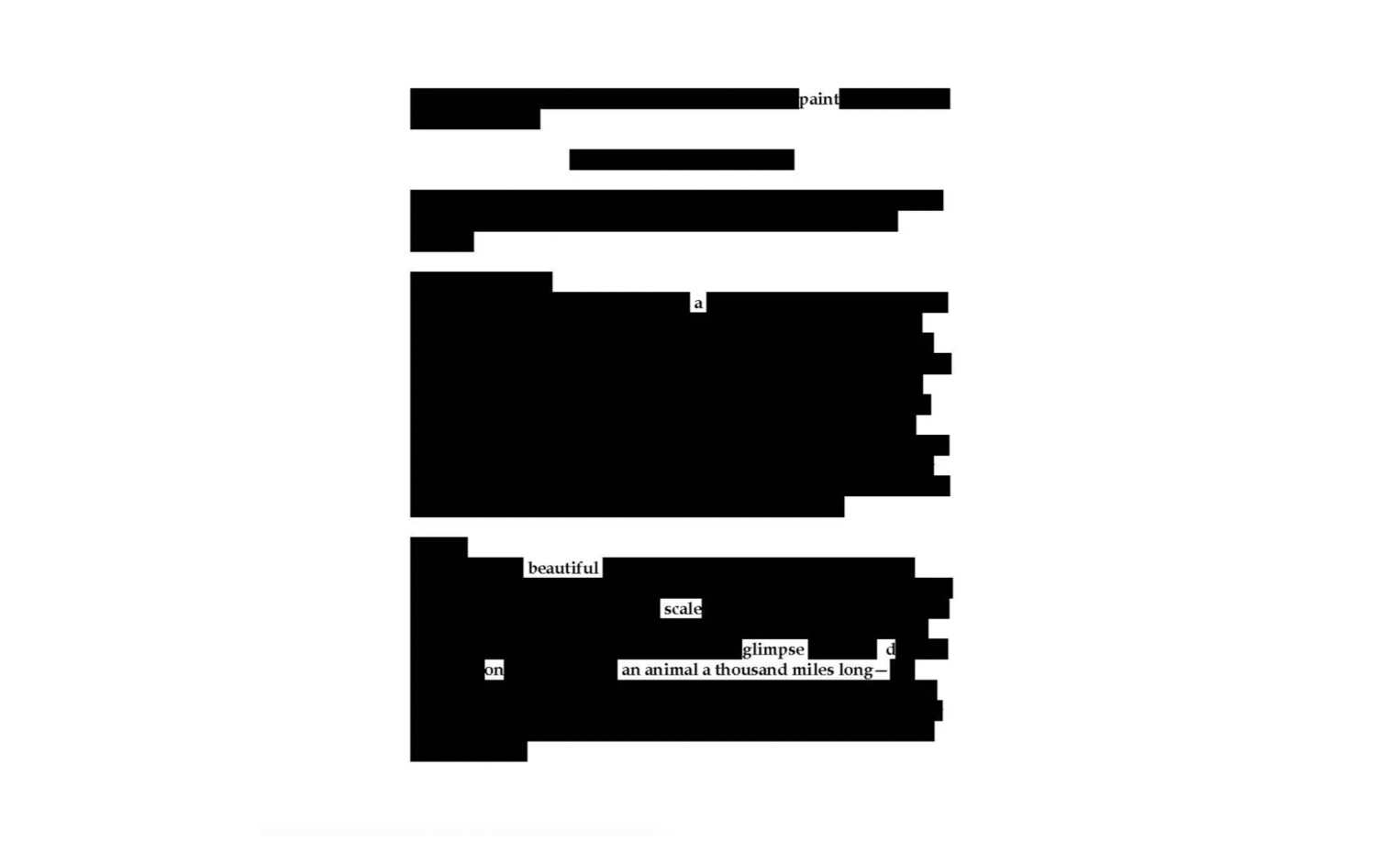

It's not a far leap, from Houle’s varied compositions, to think that any painting could serve as a graphic score, for the right performer. From there, one might wonder if any image—anything seen—could be one, too. If so, the visual configuration of any poem on a page could be seen with the suggestion of underlying orchestration, a music not in the language but in how it plays in the eye. That might be especially clear in works of erasure such as Sarah Kortemeier’s collection in the series, Aristotle’s Poetics, which extracts stepping-stone phrases from Aristotle’s text. As in the image below, the visual configuration has a performative, rhetorical effect; here we trickle from “paint” to pool at the horizon of “an animal a thousand miles long”:

The statement can be rendered as “paint a beautiful scale glimpsed on an animal a thousand miles long.” It speaks to the painting that can happen in the mind’s eye, depicted on the surface of a glimpse, and suggests that this glimpse has a sense of music, a distinct scale, within it. Kortemeier’s erasures often foreground sonic realities that might lyrically complicate Aristotle’s science of narrative, including pages with statements that can be rendered as follows:

“I am a music and there is nothing else besides”

“I mean language with my melody is a necessary part”

“I am easy to dance to I am close to speech”

“from childhood we have produced hymns we cannot identify”

“people attach their melody to objects”

The phrases of the erasures become such objects, inviting one to perceive the necessary melody of “hymns we cannot identify.” To be “close to speech” differs, critically, from the Poetics’ faith in precise articulation; it suggests both intimacy and distance, a space between where we are and what we say, however close we are to it. The chapbooks in The Offending Adam’s new series—which also includes collections by Vi Khi Nao, Jessica Q. Stark, Afieya Kipp, and others—emphasize the complexities of this closeness.