The Critic-Comptroller: On Renee Gladman’s Solo Show at Artists Space

From the barest line to the most concentrated swatch of color, every image Renee Gladman produces seems to reflect the city-state of Ravicka. Gladman, the polymathic author of fourteen books that boldly challenge the conventional boundaries of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and visual art, introduced us to Ravicka in her novel Event Factory (Dorothy Project, 2010). She describes it as a land that is “large, yellow, and tender,” where time and space come undone. In Ravicka, the architecture constantly drifts and rearranges itself—some houses are even invisible. Here, one's reality is determined more by acts of wandering, thinking, and speaking than by buildings, streets, or the laws of physics.

Since as early as 2006, Gladman has alluded to the idiosyncratic laws of her fictional world in abstract drawings, which have been compiled and published in books such as Prose Architectures (Wave Books, 2017), One Long Black Sentence (Image Text Ithaca Press, 2020), and Plans for Sentences (Wage Books, 2022). The subjects of these images, like the changing face of Ravicka, resist easy identification. For example, the abstract ink drawings in Prose Architectures do not depict famous landmarks or structurally sound dwellings. Instead, they evoke a sense of a built environment unfurling from scriptural gestures, a movement that points to Ravicka and, more generally, the feeling of rising and falling through space.

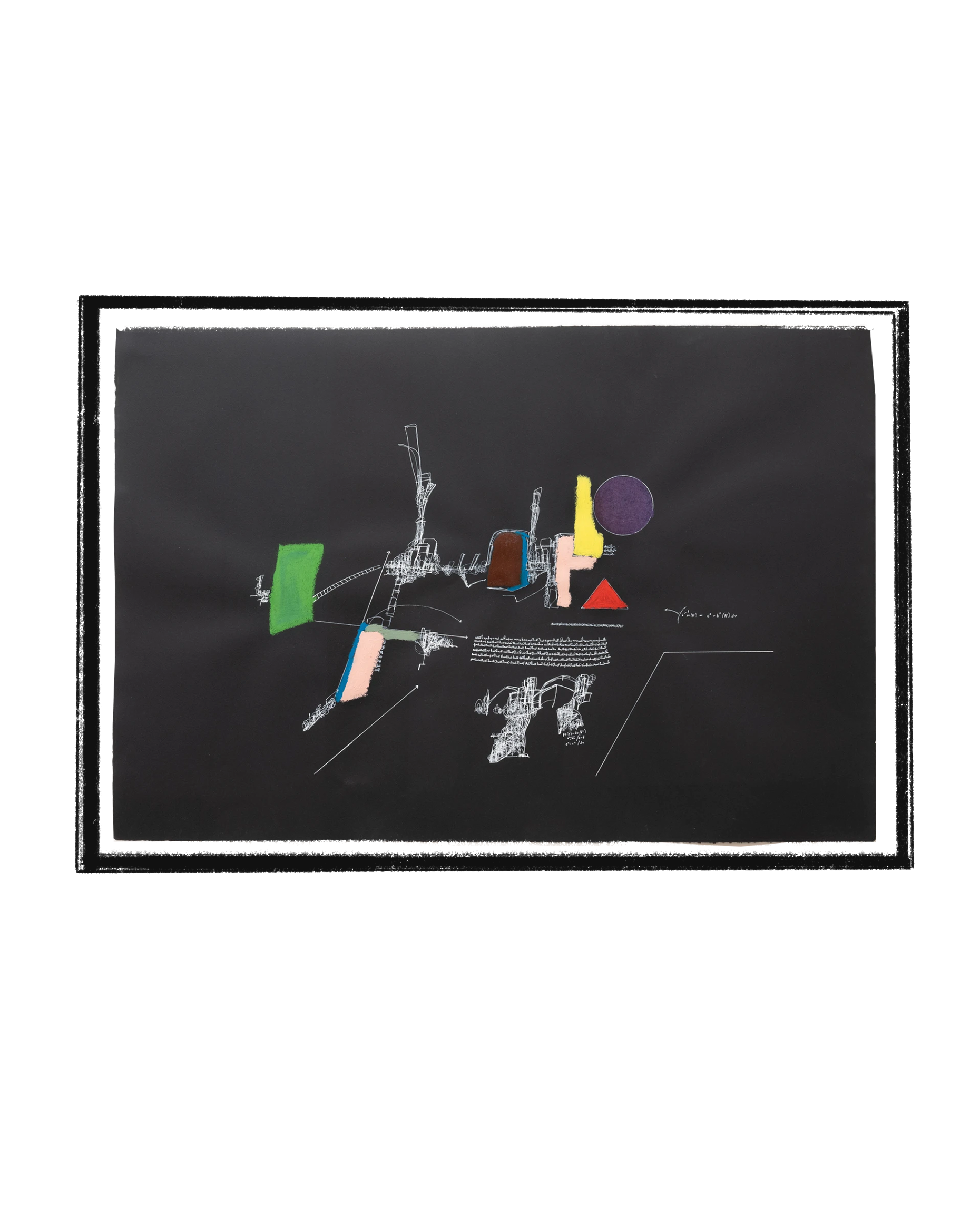

For her first New York solo show, Narratives of Magnitude, which was on view at Artists Space from January 13 to March 18, 2023, Gladman’s abstract drawings came off the printed page and onto spare white walls. Despite the change in format, the exhibit at Artists Space was a seamless extension of Gladman’s practice and appeared thoroughly driven by her vision and voice. The one-room exhibit featured twenty-five drawings on paper encased in sleek black frames. Made with pastel, gouache, and acrylic on black and white paper, all within the last four years, these drawings were uncanny and exterior, reminiscent of houses turned inside out.

The show’s curatorial framework emphasized the diagrammatic quality of the drawings, the way Gladman pares down the language of disciplines like architecture, city planning, astronomy, data science, and mathematics and holds their schematics up against the body and its senses. The first two definitions of “diagram” in the Oxford English Dictionary highlight a tension latent in Gladman’s practice and in the exhibition: “1. a figure composed of lines, serving to illustrate a definition or statement, or to aid in the proof of a proposition; 2. an illustrative figure which, without representing the exact appearance of an object, gives an outline or general scheme of it, so as to exhibit the shape and relations of its various parts.” According to the first entry, a diagram is a means to an end, with a clear and logical correlation to the physical world. According to the second, it is an approximation of an idea, and what matters are its internal relations. In one case, the drawing conveys knowledge; in the other, it deconstructs it.

Gladman wrote, regarding her drawings:

I put something in front of my not-knowing; it was a line made from a blue pastel stick. I drew the line then pulled my finger through it. I wrote ppp at its bottom right corner to put sound to my not-knowing. … I didn’t know what I was doing with the not-knowing, it was almost as if I wanted to make the not-knowing look like knowing so that I could know it.

This statement, printed on the wall at the entrance of the exhibition, suggests that Gladman’s marks serve as placeholders for knowledge that become a form of knowledge themselves. In Ravicka, for instance, “not-knowing” is an ethos and a mode of being that often leads to more robust experiences than knowledge in its usual guises. Even fundamental coordinates, such as one's position in space or the city and nation one inhabits, stand to be questioned.

How might such an ethos be embodied in a space for art-viewing? What kinds of habits must an art viewer relinquish to fully engage with the form of knowledge that Gladman refers to as “not-knowing”?

•

I suspected that Gladman had already illustrated a model of spectatorship in her previous writings, and so I revisited her Ravicka series, specifically the fourth novel Houses of Ravicka (Dorothy Project, 2017), in which Jakobi, the comptroller of the fictional city-state, searches for a missing house. The Ravicka cycle has been described as “social science fiction,” but these books are far more experimental than the label suggests. By poetically retooling sci-fi’s stranger-in-a-strange-land trope, Gladman flips a deceptively simple point of intrigue, a missing house, into a search that becomes, through a series of diversions and revelations, an exploration of the relationship between measurable, diagrammable space and the unruly human body.

In Ravicka, the task of the comptroller is to take “geoscogs” of the city's built environment, which are “measurements that keep track of a building’s subtle changes and movements over time.” Jakobi, whose gender is as mutable as Ravicka's cityscape, is awkward and cantankerous, dressed in a green striped jacket that indicates their official status. They take their job seriously but wield little real authority. One often finds the public servant passed out in the street, eating with low-ranking misfits in tents, stranded on roads, or helpless in traffic circles. Jakobi’s task bears a striking resemblance to that of an art critic: to follow a subject, be it a person, an event, or a medium, and take note of the subtlest shifts in its behavior over time. However, the rules of these respective games—art criticism and the search for a missing house—constantly shift due to the cleverness of the objects of scrutiny.

For instance, when viewing Untitled (Moon Math) (2022), the eye scans across the drawing's surface in a curious way. First, it attempts to read the textured expanse of asemic writing that covers two-thirds of the drawing's surface, like a rug with rents and stains. Then, circular forms, some transparent and some opaque, interrupt the mass of text, which, despite its disorderliness, is neatly justified left and right. One peers around the text, as if peering around the corner of a hallway, to discover a frenzy of activity: faux-equations and vectors float in an ether of wild, loopy scribbles, giving this part of Untitled (Moon Math) the appearance of a scratched chalkboard. The eye follows arched arrows around a central void. Beneath the void, mathematical expressions crammed into microscopic script appear to describe something vital: x squared over the square root of c times d squared over q minus q. What do these unknowns represent? The hypothetical critic-comptroller mimics a mathematician on the verge of a breakthrough, only to realize that what the expressions describe is not a tangible shape but the shape of “not-knowing.”

The eye’s journey across and around this and other drawings in Narratives of Magnitude resembles Jakobi’s clumsy and precarious trek through the streets of Ravicka en route to house “no. 32,” a house that “does not exist, appropriately.” “All the same,” Jakobi asserts, “it is located on Bravashbinder Street”:

From Czorcic I was to ascend the Fallender hill, then proceed through the square, but due to the “miracle parade” taking place that day, I was forced to take a detour. Being thrown off my trajectory put the afternoon’s project at risk. If I did not follow the correct parallel, I could not be certain where I’d end up. But the necessary degree was not available to me.

Thrown off course, Jakobi enters a dreaded pedestrian rotary:

It was busy that afternoon. I was spit out of it several times before I could find traction. People don’t behave well in rotaries, even those for walking. I missed my exit once and had to circle back for it; when I reached it the second time, an extended family was crossing in front of me, making my leaving the rotary impossible.

In time, the city appears to swallow Jakobi whole, leading them to wonder, "Where was the city?"

In Narratives of Magnitude, similar to the disorientation experienced in Ravicka, there is no clear map or logical progression to guide the viewer through the exhibition. Instead, improvised vectors and desire lines shape the experience. The only semblance of instruction appears in a grid of nine intimately-sized pictures titled Slowly We Have the Feeling: Scores (2019-22) that hang near the entrance. Their title connects them to Fluxus event scores, pithy instructions for participants to move their bodies, interact with one another, and rejuvenate the quotidian by disrupting its patterns (a score by Fluxus collaborator Yoko Ono, for instance, reads, “MAP PIECE / Draw a map to get lost. / 1964 spring”). Gladman’s scores are even more oblique, communicating with swatches of bright pigment on black paper, vectors, circles, polygons, angles, and curves, lines of asemic cursive, and scattered mathematical variables. They inspire reorientation and movement, loosening the body from its fixed position in space.

The critic-comptroller's encounter with disorientation and new signs pries their senses open to details and sensations that are typically suppressed by layers of interpretation and historicization. As their senses are opened, they notice the abundance of yellows, greens, roses, and purples that swirl and stack like skylines emerging from mist in the exhibition space. Gladman's use of bright, yolky yellows evokes the tender cityscape of Ravicka. Her drawings seem as if they could be woven together to create a multidimensional playground, free from the constraints of meaning and classification. The critic-comptroller gives up trying to correct their trajectory and wonders if they could use the leaning ladder in Black Wandering (2022) to scale the gray high rise in Untitled (pressure pressure infinity) (2022). They contemplate if the numerical notations in Untitled (Moon Math) describe the physics behind the architecture in Grasses/Systems (2022), which hovers over an abyss. They speculate that the notations ppp and pp connected by a rising curve in Novel Be Wind (2022) indicate volume and that all rising curves in Gladman's drawings convey the sound of a whisper dialed up to a rumble.

At the same time, the critic-comptroller’s impulse to grasp at symbols and codes, so as to make meaning of the work, risks suppressing the multivalence of drawings like Tremor Vector Still (2022), which, on first glance, depicts a confluence of block-shaped strokes made from pastel and pigment surrounding a deconstructed pentagon whose uppermost vertice sprouts a band of yellow. Like its title, the visuals of the drawing convey sensations rather than an allegory. However, a naive reader of the work, informed by a demand for transparency and understanding, could come away convinced that the pentagon was a house, a school, or a place of worship, that the yellow protrusion was a flagpole on its roof. The impulse to wrestle abstraction into figuration, gesture into symbolism, betrays an impulse to fit unknowns into familiar equations, as well as the absurdity of such an endeavor. Gladman seems aware of this, and, in works like Tremor Vector Still, leads the viewer close to the edge of identification—so close that the edge begins to appear strange and unstable.

On the whole, one could argue that Narratives of Magnitude facilitated an experience that was not the communication of meaning via a narrative or any kind of visual language, but rather an encounter with unquantifiable, unnameable difference. For the critic-comptroller—the spectator hoping to take absolute measurements and gain new and unambiguous knowledge from the show—the works on view inspired both hyper-focused reading and diverted desire. In other words, the critic-comptroller attempted to read Gladman's markings as language but, in doing so, encountered an abundance of vectors, obscured messages, and kernels of knowledge-like information. The urge to comprehend the drawings as self-contained systems of meaning, as knowledge rather than as traces of "not-knowing," got in the way of activating Gladman’s drawings. Ultimately, this urge dispersed into thin air.

•

In Houses, Jakobi eventually comes across a “strange building” that turns out to be nothing more than a facade: “Not only did it fail to present a door, there also appeared to be no windows. It was one solid, unbroken, cascade of wall.” On this hulking monolith is a detail that neither appears to be an ornament nor an accident; rather, it simply draws attention to itself. According to Jakobi, “Each time the cars filled the rotary all their lights threw a kind of beam onto the building, exposing a small square about a meter beneath the roof.” Due to the “fantastic sloping of the walls,” the square never appears to stay in one place. “What was the purpose of this square?” Jakobi asks in desperation.

Drawings, like buildings, are surfaces bearing marks (some drawings imply depth using Western linear perspective, though those like Gladman's that don't are, in my opinion, more honest). The experience of seeing Gladman's drawings, framed, evenly spaced on the walls, and perfectly lit, brought about a sensation similar to Jakobi's nighttime encounter with the "strange building" in Ravicka. The drawings, which were once pressed together on facing pages, had now become vertical surfaces, bearing inscrutable missives. They meet the viewer’s body at eye-level, both declaring their two-dimensionality and pulling the viewer toward the tension of their surfaces. In a sense, Gladman’s drawings are not just for the eyes; to quote the mysterious inhabitant of Ravicka’s House no. 32 (since even a missing house no doubt has an inhabitant), “You have to let go of the notion that sights enter the eyes, or merely the eyes.” The drawings invite the viewer to contort their body in a dance of intimacy and trepidation: stooped shoulders, folded hands, tilted head. This is because the drawings are not merely there to be apprehended. They also work on the viewer. According to the inhabitant of no. 32, the houses of Ravicka move around because, like humans, “they see,” and they possess subjectivity. In the center of a room of Gladman’s artworks, the critic-comptroller is caught in a reciprocal gaze. They realize that the drawings, like themselves, cannot be reduced to a mere knowable object.

Another way of describing this act of seeing without reducing could be to evoke the term coined by French writer Édouard Glissant (1928-2011): opacity. This refers to a state of freedom in which one's existence is not, as is often the case in Western thought, reduced to a set of easily recognizable definitions and categories of difference. In 2019, artist Vanessa Thill spoke with poet Lewis Freedman for Tripwire: a journal of poetics, and they noted how the stakes of Gladman’s work become evident in the restless negotiations between the author and her page. These negotiations, which go beyond formal play, constitute a kind of socially and politically engaged world-building. Thill and Freedman reference Glissant's notion of opacity, which the postcolonial theorist asserts is a right that belongs to everyone. Read in the context of the Black radical tradition, opacity makes room for modes of existence and forms of knowledge that are “vibrant, untamed, and free-floating.” In his book Poetics of Relation (University of Michigan Press, 1990), Glissant holds opacity against its opposite term, transparency:

If we examine the process of “understanding” people and ideas from the perspective of Western thought, we discover that its basis is this requirement for transparency. In order to understand and thus accept you, I have to measure your solidity with the ideal scale providing me with grounds to make comparisons and, perhaps, judgments.

If Gladman renders her work “opaque,” she does so to jolt the reader or viewer into an awareness that they do not, in fact, understand and that the world is not, in fact, transparent. They must approach the page or the picture with, in Thill’s, a self-conscious “humility” that is both socially and politically constructive.

One result of encountering an inscrutable presence with humility is that it can prompt a person to perceive in a new way and compel them to invent new languages to describe what they see. This new language can then be used to reshape familiar objects in everyday life. Jakobi, for example, remarks that after staring at the building well past their bedtime and throwing a rock at the unknowable square, “It was as if I had suddenly understood night.” Similarly, after leaving Narratives of Magnitude, the critic-comptroller—who, admittedly, was me—became more aware of the vectors pedestrians followed through alleys and the sharp pivots they made to avoid oncoming cars and puddles. I saw the handbag sellers on Canal Street and imagined the numerical calculations that sustain their livelihoods. Gladman's drawings do not contain subjects, such as pedestrians or street vendors, to whom these vectors and calculations belong. Instead, their dislocated gestures and floating expressions exist as a kind of event score for everyone and no one.

I began envisioning a mode of criticism—or, more broadly, thinking about art—that brings this score to life without imposing on it a kind of rigid interpretation. In Event Factory is an evocative passage in which the narrator, a linguist-traveler lost in Ravicka, is invited into a highrise by a woman unknown to her. Unlike Jakobi, who navigates the city by way of an internalized map of parallels and precarious angles, the narrator of Event Factory follows verbal instructions with innocent precision. When the mysterious woman beckons her, she enters the building, rides an elevator up twenty-three floors, and enters a room where the woman awaits. Without speaking, they enact what appears to be a ritual of greeting:

I opened the door onto a wall of books with her standing proudly before them. Her arms were folded across her chest and the smile she gave was scandalous. I walked until we were face-to-face with about a foot between us. She unfolded her arms and embraced me. ... We danced without comment. With my head on her shoulder, I read the names of all the books within view. The slenderest volumes of writing I had ever seen. One was called The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers, another Company.

These two titles are striking, and they speak to the lasting impression that Narratives of Magnitude gave me. By placing an opaque entity “in front of my not-knowing,” the show insisted that I work to imagine a mode of criticism resembling less the curmudgeonly comptroller fumbling against the flow in a maze-like traffic circle and more the dance of two bodies inventing a language as they go.

Which is to say, the tension of an interrogation—such as a body striking against a strange building at night—can sometimes resolve into companionship, and the desire to see and to know can sublimate into a happily indescribable feeling of coordinated movement.