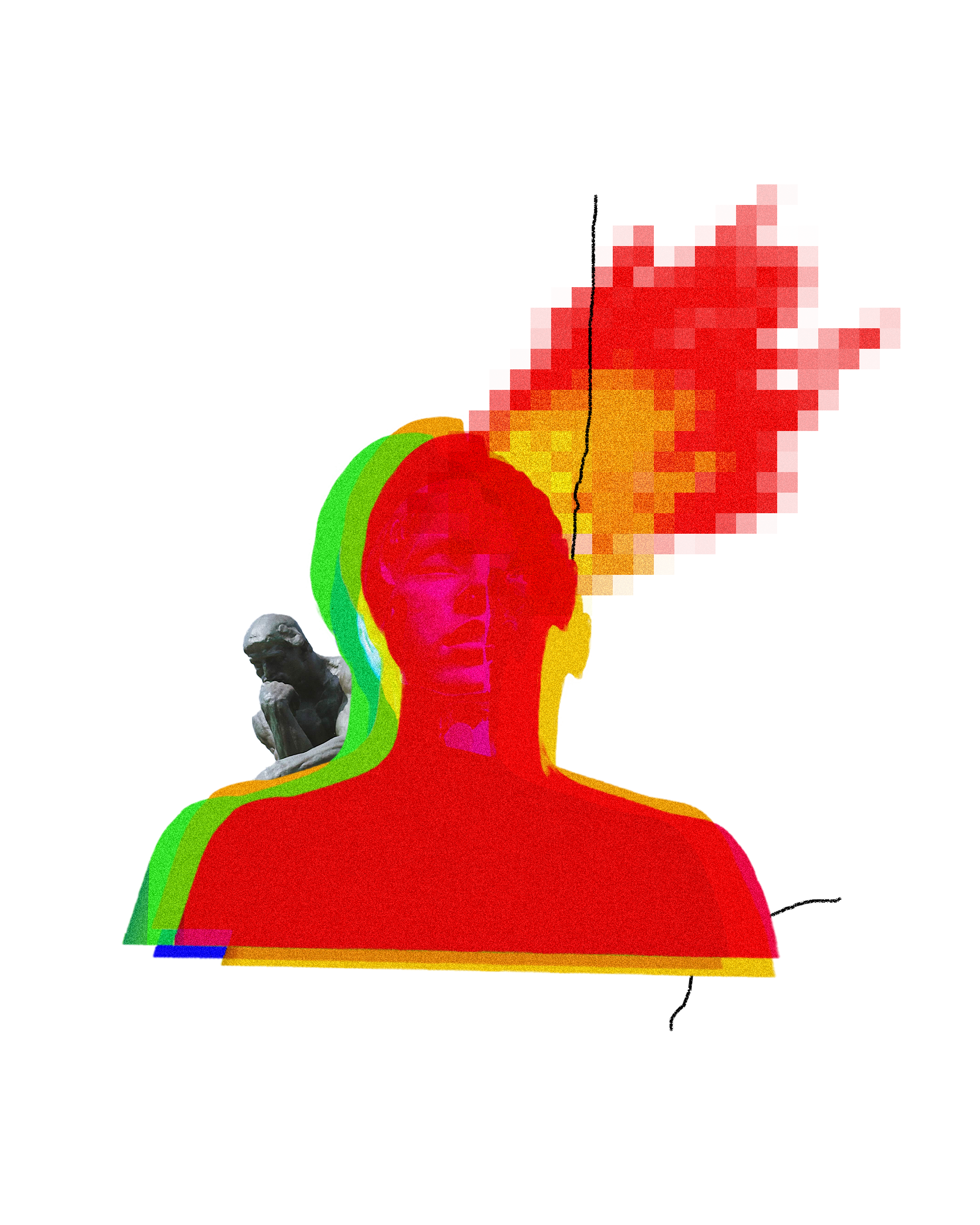

On Bellows and Rodin: Stag Fights, Explosions, and Spectatorship

“What makes my Thinker think is that he thinks not only with his brain,

with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils and compressed lips,

but with every muscle of his arms, back, and legs,

with his clenched fist and gripping toes.”

—Rodin

For seven and a half minutes, a fuse burnt not far from the still-icy shores of Lake Erie. At the end of the fuse was a cheddite pipe bomb, an explosive roughly equivalent in power to three sticks of dynamite. The pipe rested on a marble plinth outside the Cleveland Museum of Art and on that plinth sat a 900-pound bronze casting of Auguste Rodin's famed work The Thinker. It was 1:00 AM on a Tuesday in 1970. With every second, the fuse burned shorter. Alone or in a cohort, someone on the scene hastily scrawled “off the ruling class” on the plinth.

Inside the Museum, the figures of two boxers stood engaged in an endless, wordless struggle. Stag at Sharkey's, the most famous painting by Ashcan School painter and Ohio native George Bellows had hung on their walls since its acquisition in 1922.

For seven and a half minutes, the fuse burnt outside the museum. Its tiny kiss of flame running closer to detonation, to destruction.

•

Tom Sharkey was born in Dundalk, Ireland in 1873. Reports have him running away as a child and sailing to America as a cabin boy. He landed in New York City where he worked as a blacksmith before enlisting in the US Navy at 19. Stationed in Hawaii, he began boxing and acquired the fighting name “Sailor Tom.” He would emblazon that persona across his chest with a large tattoo of a star just below the neck and a four-masted warship stretched along his broad pectoral muscles. Entering the ring, he would sometimes call out “I'll never give up the ship!”

In those years leading up to the turn of the century, the Marquis de Queensbury rules were standardizing—and to some, domesticating—the wild and rough world of prizefighting. But Sailor Tom was a heavyweight of an older school. Not so interested in technique and precision, Sharkey entered the ring for blunt force trauma. The Milwaukee Journal noted in 1898 that “It is very probable that he [Sharkey] will never be able to fight strictly within the Marquis of Queensbury rules, and he is likely to lose important battles through his foul tactics.” He was muscular and sturdy, “endowed with the grain of the wind tossed oak” according to another newspaper report, “built to withstand the hurricane and the flood.” He was, simply put, a bruiser.

Though Sharkey would never hold the heavyweight title, he nevertheless was a prominent figure of his time, battling all the top heavyweights and never allowing those champions to make an easy night of it. He was a likable and marketable opponent and his losses were always close, prompting more than one rematch. Sharkey faced Joe Choynksi (three times), Jim Jeffries (twice), James Corbett (twice), Bob Fitzimmons (twice), and Peter Maher (twice). Fleshed out with a rogues gallery of opponents known only to history by such colorful names as “Punch Vaughn” or “Rough Thompson,” Sharkey's record stands at 37 wins, 7 losses, 6 draws, and 2 very cauliflowered ears.

Gentleman Jim Corbett would later remark of Sharkey: “He couldn't box much, but he was about as wicked a man to tackle in the ring as we ever had. If he couldn't hit you he could pretty near squeeze you into a pulp once he got hold of you.” After retirement, Sharkey toured the vaudeville circuit and opened an on-again-off-again saloon in Manhattan's West Side, Tom Sharkey's Athletic Club, where the Lincoln Center now stands. This is the “Sharkey's” memorialized in George Bellows' Stag at Sharkey's.

Joyce Carol Oates once called boxing “a celebration of the lost religion of masculinity all the more trenchant for its being lost.” Boxing has come a long way since Sharkey's time and it isn't just the Marquis of Queensbury rules anymore. Decriminalized in the eyes of the law and regulated by state commissions, boxing is no longer relegated to barroom stag fights. It has become a slick package sold by television producers. And now social media, too, has been at work smoothing out the fighter's rougher edges. Now, there are loads of good and even great fighters out there but men like Tom Sharkey? They don't come around every day. Sailor Tom certainly belonged to that “lost religion.” Heck, he might've even been its high priest.

•

Most of us can recall the image of Rodin's The Thinker. Motionless, muscular, and nude, the figure sits alone in his now-famous pose: leaning forward, his chin rests on his right hand, his right elbow propped upon his knee. Though he is at rest, the contours of The Thinker are a history of movement, of struggle. His body appears strong, well-muscled. Thick forearms and defined calf muscles suggest a workman's body, an athletic and physical existence beyond the implication of his title. His form suggests action and strength and perhaps even the capacity for physical violence.

This solitary figure we are familiar with was not Rodin's initial vision. The Thinker was originally designed as a part of a larger whole. That work was The Gates of Hell, commissioned from Rodin in 1880. It is a massive functioning doorway featuring a swirling depiction of Dante's visionary Inferno. In all, more than 180 figures comprise the complete piece, covering the door frame as well as the door panels. The Thinker sat near the top, centered above the doorway, looking down, pondering the scene below him. There, the figure was actually named The Poet, likely a reference to Dante. Foundry workers casting The Gates of Hell suggested the new name to Rodin. Broken from his original context, separated unto himself, The Thinker now stares out to nothing in particular. He becomes like so many great works of art, a sort of Rorschach test for the viewer, an empty vessel into which we can project our own anxieties or hopes or fears.

In The Gates of Hell, The Poet sat just over two feet tall but Rodin loved the figure he created. He began displaying it as a solo piece. Rodin soon realized it would benefit from being enlarged, so he re-cast the figure into the scale we are accustomed to. Now nearly seven feet tall, The Thinker takes on heroic proportions. There are 25 such large-scale bronze castings of The Thinker. Less than 10 were made during Rodin's lifetime, under his supervision. The Thinker that sits in Cleveland is one such casting, acquired by the Museum in 1917.

A year earlier, the poet Florence Earl Coates of Pennsylvania wrote a poem contemplating the already well-known statue.

The "Penseur"

(On Seeing the Famous Statue)

Rodin's it was—this vital thing, this Soul,

This striving force imprisoned in clay,

This monster Shape inert, held in control

By that it doth enshrine:

Rodin's it was; but, ah, to-day

It is the world's—and mine!

What mystery here is meant?

Is this Time's great event—

This creature earthward sent

With subtle might against himself to strive—

To struggle upward from the brutish thing

And, ruling the blood's rioting,

Keep the celestial spark in him alive?

What miracle is meant,

Suggested by this frame relaxed and bent?

What wonders to this Titan are revealed,

Sitting enisled and motionless as if

Lone on some cloud-invested Teneriffe?

Inward and inward still his vision sinks.

What does he here?—He thinks!

Thought is the travail that absorbs him thus;

Himself the workshop, most mysterious,

Wherein are wrought what human strengths there be.

Detached, aloof, with eyes that seem to stare

Beyond us and beyond apparent things,

He gazes far into futurity,

And doth with gods unbourned horizons share.

For thoughts, upborne on never-tiring wings,

Boldly adventure regions foul and fair:

To Hades sink, then rise to Heaven again,

Still finding everywhere

The mystic threads whereof are joy and pain

Shaped in the penetralia of the brain!

For Coates, The Thinker is a noble figure, lofty in his human ambition. The body, “this brutish thing,” is physical, earthbound. But the mind possesses a different quality, allowing The Thinker to sink to Hades and rise to Heaven, to convert himself from flesh into this “the workshop, most mysterious.” For Coates, The Thinker's train of thought moves “inward and inward” towards a self-contained and solipsistic destination, a sense of self as island.

Placed above The Gates of Hell, The Poet contemplated others. Seemingly at a remove from the action, he remained aware of their torment and suffering, even though he didn't appear to be suffering himself. The Poet was an audience of one, witness to the pain of others. We viewed him in his position of viewership and so ultimately we viewed ourselves. It is natural to ask: Did The Poet imagine the scene he beholds? Are the gates of Hell merely the gates of his own creative mind? Or is The Poet watching the world unfold before him, contemplating how to describe it? What I mean to ask is, How responsible is The Poet for this Hell? What responsibilities does he bear?

The Thinker has “struggled upward” from Hades and divorced from context, we lose the ability to discern the focus of the sculpture's attention. We are forever incoversant with what The Thinker actually thinks. He is solitary but he is not alone. We intrude upon his solitude. He stares off, not entirely at us but not entirely past us either. “This striving force imprisoned in clay,” he appears absorbed or partially absorbed in memory, those unseen visions. The Thinker is a haunted figure, intruded upon by the past.

Is it Hell that intrudes upon The Thinker? Is this a kind of violence? Hell is usually cast as a place of torment, anguish, the “gnashing of teeth.” Torment is an interior experience; violence is external. Seated on The Gates of Hell, The Poet commented upon the suffering of others, making art from their fate, their pain. As The Thinker, the pain is only implied. The suffering is ours. We are his Hell.

•

“I don't know anything about boxing,” the painter Geroge Bellows once remarked. “I'm just painting two men trying to kill each other.”

It was at Sailor Tom's New York saloon, Sharkey's Athletic Club, that George Bellows sat and watched the pugilists—potential killers, as he put it—he would later paint. Stag at Sharkey's was painted from memory and it gives the impression of having been painted quickly. The brush strokes are kinetic and gestural. One can see the impasto evident in the brightly lit main figures, the textured paint laid heavily upon the canvas, brushstrokes plainly visible. One critic writing later of Bellows says that his “slashing brushstrokes themselves are a violent act, magnifying boxing's anxiety and vehemence toward the perfected body.”

In Stag at Sharkey's, the bodies of the fighters collide with one another creating a triangular form that dominates the composition. At its point are the boxer's heads. They are nearly identical, a mirrored image quite literally bleeding into one another, an indistinct impasto of violence. The sense of simultaneity in the paint continues down the bodies of the boxers, their anatomy confluent, overlapping, blended. A tangle of painted flesh, blurred as if too quick to be painted, this is not perfection nor is it imperfection. It is an immediacy, an affect, a feeling. Although we lose some of the detail, we understand the sensation, the movement, the ferocity.

A similar pell-mell effect is achieved with the ropes. Behind the fighters we see three ropes, evenly spaced and perfectly horizontal. But in the foreground, between us (the viewers) and them (the fighters), we see only two ropes. Unrealistic, improbable, it is technically an error but these two foregrounded ropes run askew, creating an angle more effective than the correct three ropes would have achieved. They draw the eye naturally leftward across the canvas. Their angle implies action, movement, a subtle chaos. Here, as with Bellows' brushstrokes, accuracy is discarded in favor of action. Bellows keeps us in the heated moment of an unpredictable stag fight, ringside where things are not so neatly contained. Having sacrificed a rope in the name of composition and movement, we are less protected, less separated from the action. From our vantage point in the audience, the ring is that much more permeable a space.

Bellows had moved to New York City from his native Columbus, Ohio in 1904, first living in a YMCA. He would draw on some of his experiences there, depicting scenes of physical culture in “Business Men's Class” (1916), a lithograph depicting what Bellows described as “brain workers taking their exercise,” and a year later with another YMCA lithograph, “The Shower Bath,” depicting a group of heavier-set men exercising. Himself a gifted athlete, Bellows had rejected an offer to play professional baseball in order to pursue his interest in painting. These lithographs demonstrate Bellows' satirical and slightly contemptuous view of the non-athlete in an athletic setting.

Setting up a studio at Broadway and 66th with fellow artist Edward Keefe, Bellows had ample time to visit Sharkey's. Prizefighting was technically illegal in New York at the time, but you could pay a dollar or so for a “membership fee” and be allowed in to watch the fights unfold. Bellows explained in a letter to the director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, “Before I married and became semi-respectable, I lived on Broadway opposite The Sharkey Athletic Club where it was possible under the law to become a 'member' and see the fights for a price.”

Geography yoked Bellows and Sharkey together, rent and real estate making unexpected neighbors of these men. And the raw images he created based on those visits is markedly different from his more refined YMCA lithographs. Bellows' style made him a leading figure in what is known as the Ashcan School, painters who favored everyday, commonplace social scenes. The term Ashcan School wouldn't be coined until later. Originally, those painters were known collectively as The Eight or, less flatteringly, as the Apostles of Ugliness.

Painting, no matter how frenetic in appearance, is necessarily static. We are obliged as spectators to take our time, to contemplate, to notice. But to watch a sport live is to witness an often impenetrable series of acts: too many body parts moving too quickly to be comprehended completely by the viewer. Some action, always, is missed by the eye. And boxing in particular is subject to this fast-paced inscrutability. Blink and you miss a flash knockdown. Glance down at your wristwatch and the fight may be over. It is action and it is fleeting. Incomprehension is a part of the sport.

Bellows illustrates the tension that underpins both the sport and the spectacle: the not-too-concealed knowledge that a street brawl lies buried just below the surface of the sweet science. “Boxing does not look the way that Bellows painted it,” noted art critic Paul Richard for the Washington Post in 1982. “But that's the way it feels.”

•

The fuse burnt down to its final red inch on that cold morning in Cleveland. It was 1:00 AM in late March when the cheddite bomb detonated outside the Cleveland Museum of Art. The explosion sent Rodin's cast of The Thinker into the air, briefly. It landed rudely upon the ground not far from its plinth, coming to rest face down, “apparently contemplating Hell much more directly” as one writer put it. The bomb had been placed at its base; the statue's feet were blown off to the ankles. The base was severely damaged and the force of the explosion actually expanded the sculpture's entire lower half, peeling the legs back like petals from a flower. Shrapnel cut through the crisp air, damaging the bronze museum doors and chipping the marble columns.

Whoever lit that fuse, whoever constructed the pipe bomb, whoever placed it between the feet of The Thinker that Tuesday morning in 1970, was never caught. The message “off the ruling class” was hidden from public knowledge for years.

Much suspicion was thrown towards the Weather Underground, a loosely-affiliated radical-left group that had committed a number of bombings around the US at that time. This accusation was never leveled formally and it has never been confirmed but it's a pretty close match. Weather Underground members had an active presence in Cleveland and were known for building and detonating explosives, among other actions. But The Underground typically bombed less esoteric targets—the Pentagon, for instance, or military induction centers and police stations. They broke Timothy Leary out of jail and successfully evaded the FBI for years. They often issued evacuation warnings and took credit publicly for their attacks, issuing statements that outlined particular grievances. In all their bombings, no one was killed or injured. Targets were symbolic but direct.

The Weather Underground did take credit for bombing one statue, however. In Chicago, police officers had erected a statue in Union Park honoring officers killed during the 1886 Haymarket Riot. It depicts a Chicago policeman with his right hand raised. The Weather Underground blew it up on Oct 6, 1969 shortly before the so-called Days of Rage. Police rebuilt the statue and re-dedicated it on May 4, 1970. A few months later, the Weather Underground blew up that one as well. Someone called local newspapers on behalf of the Weather Underground, reportedly saying: “We just blew up Haymarket Square Statue for the second year in a row to show our allegiance to our brothers in the New York prisons and our black brothers everywhere. This is another phase of our revolution to overthrow our racist and fascist society. Power to the People.”

But in Cleveland, no one took credit for the bombing. No statement was issued. No grievances were levied, save for the general scrawl “off the ruling class.” And the police never made any arrests. But the general consensus settled on blaming left-wing radicals generally even if they couldn't be prosecuted specifically. It could have been the Weather Underground, or an ally, or a copycat. Over the years, occasional rumors would spring up, vague and usually anonymous claims of knowing who lit the fuse that cold Tuesday morning. One of the more interesting confessions came in the form of an essay, published anonymously in a 2017 issue of the magazine Cabinet. Though the author does not explicitly claim membership with the Weather Underground, the tone of the recollections fit.

“And so there was a mood, among some,” writes the anonymous author, “that to bomb The Thinker was not simply to blow up the grim figure of surveillant white patriarchy, but actually to blow up thought itself—as the perennial antithesis of action.”

•

“But there aren't many ways to describe a fighter in training—it's muscle and sweat and grace, it's the same thing over and over.”

—James Baldwin, on writing about Patterson vs. Liston

“Human violence exploding publicly.”

—Jean Paul Sartre, describing a boxing match

“Torment, a canonical subject in art, is often represented in painting as a spectacle, something being watched (or ignored) by other people. The implication is: no, it cannot be stopped—and the mingling of inattentive with attentive onlookers underscores this.”

—Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others

“What is reckless on the stage is splendor in the ring.”

—Mike Tyson, describing his one-man show

“I must not forget that at certain times when my headaches were raging I had an intense longing to make another human being suffer by hitting him in exactly the same part of the forehead.”

—Simone Weil, from Gravity and Grace

“Art is unresolved, otherwise it is uninteresting.”

—Matthew Barney, speaking to the New York Times

“And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed.”

—Ada Louise Huxtable, on the demolition of Penn Station

•

The Thinker wasn't the only work of art damaged in northeast Ohio during that radically tumultuous period. On May 4, 1970, a gang of armed National Guardsmen swarmed the campus of Kent State University. Before they left, they shot and killed four unarmed students, some of whom were not even attending the protests the Guardsmen were ostensibly there to quell. Estimates place the shooting at nearly 70 rounds fired in just about 13 seconds. Students Allison Beth Krause, Jeffrey Glenn Miller, Sandra Lee Scheuer, and William Knox Schroede were killed. Nine other students were injured, including one who was permanently paralyzed. Local police swept the campus, removing all evidence and making it impossible to charge, let alone prosecute, anyone in the murders.

In their melee, one of the Guardsmen's bullets struck Solar Totem #1, an abstract steel sculpture by area artist Don Drumm. The bullet pierced one of the sculpture's steel plates, leaving behind a small, identifiable bullet hole. Initially, some tried to claim this hole was evidence that the anti-war protestors had fired at the Guard. They hadn't. Drumm himself was called in to perform a ballistics test using a similar piece of steel. By matching the two bullet holes, was able to prove the damage to his sculpture was caused by the Guard.

At the artist's urging, the hole has never been repaired. The sculpture was indelibly redefined that day in 1970. It bears a scar of the violence it witnessed, run through with violence, a silent testament and reminder of the damage visited upon the campus by outside aggressors. It is a sturdy work of art, accessible to the touch of the public and half a century later, students still interact with it. They decorate the statue, particularly around the May 4 anniversary. Lit candles drip wax along the steel plates of Solar Totem #1, like blood, like tears. Students write their emotions in chalk, commenting upon the bullet hole, the wound we share.

•

George Bellows visited and revisited the sport of boxing in his work many times through drawings, lithographs, and six full oil paintings which he completed in two bursts of three.

The first of these informal triptychs comprised Club Night (1907), Stag at Sharkey's (1909), and Both Members of This Club (1909). These three works are similar in themes and design: in each, two anonymous boxers clash in the center of the canvas, both the ring and the composition. The images are rough and ragged and full of action. Bellows would periodically create drawings and lithographs of boxing, often to illustrate magazine stories, but he did not complete another oil painting of the sport for nearly fifteen years. His second triptych consisted of Introduction of John L. Sullivan (1923), Ringside Seats (1924), and Dempsey and Firpo (1924). These later paintings are cleaner in appearance, more refined. They feature more complex compositions and the use of famous fighters lends the images overt, explicit narratives.

When Bellows painted Stag at Sharkey's in 1909, prizefighting was illegal in New York. Fights were held in private, members-only clubs where the boxers would be made temporary members for the evening, as would the patrons. Skirting anti-boxing laws, as they did at Sharkey's Athletic Club, saloon owners would advertise the evening's entertainment not as prizefights but as legal “exhibitions of physical prowess.” By 1922, when the Cleveland Museum of Art acquired Stag at Sharkey's, the sport's status had improved somewhat but boxing was still in the realm of the outlaw, if not always by statute than certainly by reputation. To depict boxing was to depict the quasi-legal, the slightly dangerous, and the nearly criminal. Bellows' boxing paintings would have carried this charge, the thrill of the prohibited. Lurid, evocative, and with its alliteration, even a little poetic, the title Stag at Sharkey's makes the painting's criminal element explicit.

An anecdote tells us something of the attitude with which Stag at Sharkey's was received by the Cleveland Museum of Art. Stag at Sharkey's was not, in fact, the painting's original title. When Bellows painted them, the titles Club Night and Stag at Sharkey's were reversed. But when the Museum bought what was then called Club Night, they asked Bellows if he would switch the titles. Bellows agreed. Why make this change? The Cleveland Museum of Art no doubt recognized that the sensationalism of the title would sell and that they could capitalize on the illicit content. Even in fine art, boxing gets marketed as a sideshow sport.

Stag at Sharkey's transports us, if even just for the instant, into a place we know we do not belong. In this way, Bellows' painting reminds me of the unflinching black and white photographs of Weegee Working in the decades after Bellows, in 1930s and 1940s New York City, Weegee carried a police band radio and followed officers at night into active crime scenes, documenting the grim and the guilty. The images he captured, such as candid shots into the backs of police paddy wagons, conveyed the sensationalism of the margins. He offered viewers the thrill of flouting the law, of getting away with it. Or the thrill of getting caught, the shame and the notoriety. This criminal element adds an emotional dimension to Stag at Sharkey's that is difficult to quantify, a slight racing of the heart, a boost of adrenaline that dilates the eyes and heightens the experience. The stag fight is fugitive content, not quite condoned, and looking at the painting brings us one small step closer to the outlaw that lives within each of us.

In Weegee's photographs, the camera lens stands in for the singular eye of the viewer. But in Stag at Sharky's, we are conspicuously not alone. While the focus is on the two fighters, a host of almost otherworldly figures fill the canvas. Bellows has painted the audience as a series of crude and vulgar caricatures, gestural, guttural, and primal. The paint is ghostly thin, their faces scumbled using a dry brush. They are trace elements, hints and innuendos of men only. As they leer out from the dark, the darkness becomes almost a violence in its own right. “I am not interested in the morality of prize fighting,” Bellows once said. “But let me say that the atmosphere around the fighters is a lot more immoral than the fighters themselves.” The visages in Bellow's audience are twisted, contorted in a dark paroxysm of agony and ecstasy. The joy of vicarious brutishness rests easy on their brows. They are a gang, a mob, an embodied bloodlust set loose round the ring, free to wallow and indulge their basest selves.

There is one figure in Stag at Sharkey's who differentiates himself from the others. He turns away from the fight. He makes eye contact with us as he gestures to the ring, smiling suggestively, motioning us to keep watching. His turning away does not suggest he rejects the fight but that he in fact approves and, going further, encourages us to participate in the witnessing. We are the viewer but through him we are also the viewed. He intrudes upon our aloofness from the mob around us. He interrupts our otherwise direct relation to the ring, our affinity with the fighters instead of the crowd. In making eye contact, we become self-aware of our place in the witnessing audience.

It is interesting to compare Stag at Sharkey's to actual fight film that exists of Sailor Tom Sharkey. When Sharkey fought Boilermaker Jim Jeffries in 1899, strings of lights had to be brought in, over 400 bulbs in all, to light the ring enough for the cameras to work. The bulbs reportedly burnt so hot they caused blistering on the scalps of the fighters and their hair fell out later in the week. The fight went the distance – a brutal 25 rounds – and the actual film was reportedly over 7 miles in length. That film has been lost. however. The only images we see of the fight are fragments of a pirated, bootleg film shot from the audience, the illegal camera was allegedly concealed in a cigar box.

This camera, like the perspective in Bellow's painting, is at eye level. In both cases, our view of the ring is partially obscured by silhouetted figures. We are immersed in the crowd, experiencing the action both privately and publicly, singularly and collectively. The ghoulish faces of Bellows and the heat from the lights burning Sharkey's scalp; we are with The Poet at The Gates of Hell. We are, in both cases, witness to something we ought not to see. In the moment, we are standing where we ought not to stand. In the trespass and the violence, we are the viewers and the participants.

•

After the bombing of The Thinker, the Cleveland Museum of Art was unsure how to handle the attacked sculpture. A number of options were considered. Experts were consulted. They contacted metallurgists about the feasibility of their options and they spoke to Rodin experts to hypothesize what the late artist may have thought. They came up with three possibilities: 1) Seek a replacement casting of the statue, 2) Use partial castings to repair their damaged statue, or 3) Display the piece as is, with minimal restoration.

Damaged artwork is not without precedent, of course. Many sculptures from antiquity are missing components (fingers, arms, heads – the same body parts most often damaged on boxers), through damage, vandalism, thievery, or modesty. One famous rumor claims that in the Vatican there exists a collection of marble genitalia removed by the Church. A more modern example is Marcel Duchamp's life work, The Large Glass. Contained within two panes of glass, it was cracked during shipping and the artist famously declared it “finally unfinished.” Rodin himself was no stranger to partial sculptures, once displaying a headless plaster cast of The Thinker.

Ultimately, the Cleveland Museum of Art would decide to display the exploded Thinker as is, with minimal repairs. They added a small, relatively nondescript note to its base: “Damaged 24th of March 1970”. This note would be changed some years later: “Tragically damaged through vandalism March 24, 1970.”

The Thinker continues to rest outside the Museum. No longer overseeing the tortured souls of Dante's Inferno, The Thinker now looks out upon a finely manicured sculpture garden and pond. His base is still flared out hollow as a bell, the shape of the explosion preserved and displayed. When the art critic Sister Wendy visited the exploded sculpture, she noted that acquiring this patina of history, even this violent history, has not lessened the humanity of Rodin's work but deepened it. “He’s been plunged into it; he’s exposed as vulnerable, and that makes him peculiarly, and tragically, accessible.”

In his book-length sequence of poems Bombing The Thinker, Darren C. Demaree details all of this: the placement of the bomb (“a heaven/ so fallible that/ explosives found it”), the intent of the bombing (“they scrawled a message/ on the base of the statue/ & erased it, almost, with fire”), the explosion (“I can tuck// almost a feather/ in my ribs, that's how/ close I am to flight”). His book weaves together multiple perspectives. Sometimes the poems are from the point of view of a Museum visitor. Other poems are from the point of view of The Thinker himself.

A contradiction haunts Demaree's poems. There is enough meaning concentrated in the exploded Thinker to warrant a good book of poems but Demaree is unable to finally pin down this meaning. In the final moments, it escapes him. There are thin moments when he moves to moralize but these moments ring false, like the words of a child made to apologize for something he feels no guilt over. The application of synthetic morality can only ever be superficial, a bandaid applied to the crater of a cheddite bomb. Perhaps it must be this way with violence, mysterious. “To have great pain,” writes Elaine Scarry, “is to have certainty; to hear that another person has pain is to have doubt.” There is a mystery to pain, or more specifically to the pain of others. We cannot feel it and therefore we cannot know it. The silence of The Thinker is the correct pose for such a scarred figure. We cannot understand.

It is much more than the ropes that separate the boxers from the audience. The gulf is more profound than physical. We can cheer and boo and cringe with every landed punch, yet we are beset with doubt. We never possess the certainty with which they experience the fight. We agonize over it though we rarely acknowledge it, concealing or outright ignoring what it might imply: responsibility. What we, the audience, is responsible for. We do the same with history as we watch it turn one day into the next. It was dumb luck that no one should be out in Cleveland that night in 1970, no one jogging or walking their dog, to be struck with shrapnel at the base of the skull, a piece of Rodin's bronze Thinker turned potentially lethal projectile. Sculpture into shrapnel.

The Thinker exists now, unrepaired forever in a dialogue, the work of art and the intervention. The Thinker who once pondered the flames of Hades was toppled by flames, a cheddite pipebomb, a little bit of Hell attached to a fuse. It is almost too neat. Thought and action, both symbolically represented, brought together. The same in boxing: real violence contained in the symbolic ring. It is difficult not to be confused, difficult not to doubt.

And around all of this, the self-indulgence of spectatorship. “We/ righted his figure,” writes Demaree, “but we did not/ do it because he needed us to.”