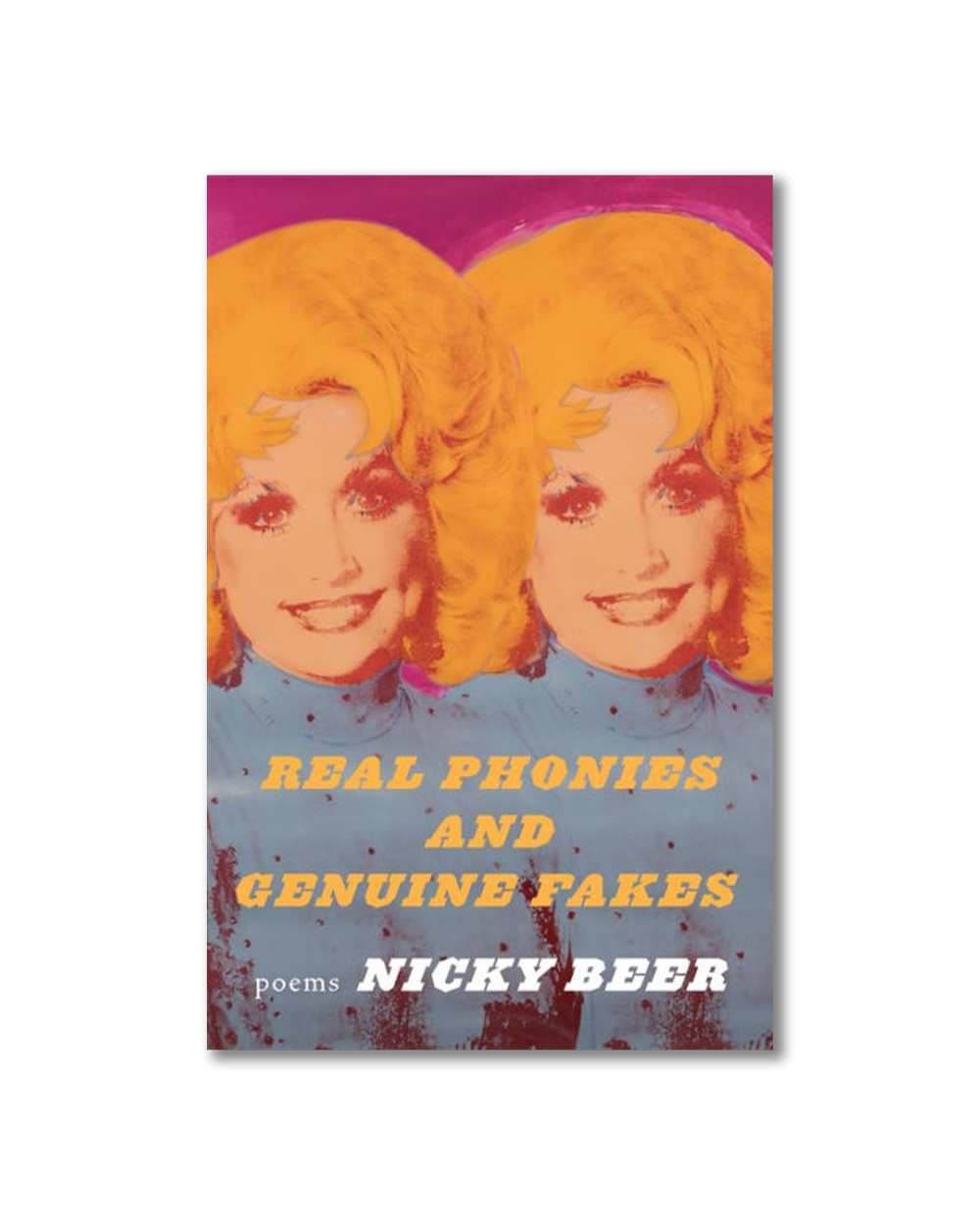

Fake Selves and Real Grief: On Nicky Beer's "Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes"

Nicky Beer | Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes | Milkweed Editions | 2022 | 88 Pages

Nicky Beer begins her newest poetry collection Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes with an epigraph from Bjork: Don’t let poets lie to you. An upfront warning, and one that readers should take to heart as her collection proceeds to craft fibs, fables, and fictions that expound on the many ways in which we lie to ourselves and allow ourselves to be lied to. Hollywood and the realms of performance serve as the collection’s focal point, these spaces of a dually-consented fabrication, the audience aware that they’re being lied to, allowing themselves to believe the lie anyway. The three line poem, “Sawing a Lady in Half,” puts it succinctly: “they want it to be true / and don’t want it to be true / that they want it to be true.” Interested especially in plagiarism and magic, Beer calls into question the validity of any singular existence, insisting throughout her text that each person is split, the separate versions of ourselves simultaneously duking it out and wiping the blood from the corners of each other’s mouths.

As a queer man who worships at the feet of Dolly Parton, the opening poem in the collection, Drag Day at Dollywood, strikes a deep chord with me. The poem establishes a theme of self-multiplicity via America’s most beloved big-wigged country artist. “A bus from Atlanta / unleashes two dozen Dollys in matching bowling jackets…” Throughout the park, hundreds of Dollys live out their own particular experiences, each with a different shade of lipstick, but every one of them blonde. Within this multiplicity, there’s bound to be contradiction.

Dollys line the perimeter of the bald eagle sanctuary,

watching raptors swoop stoically on the other side

of the enclosure. “They mate for life!” Dolly exclaims,

reading from Wikipedia on her phone. “Awww,” Dolly says.

“Ughhh,” says Dolly.

Some versions of ourselves, beyond contradicting, may offend or affront other lesser known versions: “Dolly, with weary patience, explains to Dolly / why she can’t pet her service dog.” But even as she roots this collection in the power of certain lies, Beer spouts truth on every page. As much as we would like every version of ourselves to be on stage, receiving a standing ovation, we hold within us plenty of other selves vomiting “purple / slush and kettle corn into a bank of azaleas.” Ultimately, Beer posits this split of the self as a mode of affirmation and support, as in this final image from the opening poem:

Dolly, exhausted and sunburned, collapses

onto a bench, rests her head on Dolly’s breast

who rests her head on Dolly’s breast, who rests

her head on Dolly’s breast on Dolly’s breast.

Elaborating on the theme of the self divided, Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes includes a series of poems on The Stereoscopic Man. “stereoscope: An optical illusion through which two slightly different images… of the same scene are presented, one to each eye, providing an illusion of three dimensions.” These poems play with the image of a man split down the middle, incomplete, yet also doubled. Troubling for the character of the Stereoscopic Man is the prospect of who exactly he might be: “He is neither the man / on the right nor / the left.” Unlike the split selves of Beer’s opening poem, the Stereoscopic Man cannot rely on his multiple versions. He is not bolstered by his duality, but deeply confused by it. “He doesn’t know how he happened.” This confusion doesn’t prevent the Stereoscopic Man from living a full life, or even twice the life one normally lives, as the titles of the later poems might suggest: “The Stereoscopic Man Takes a Lover,” “The Kindergartner Talks to The Stereoscopic Man,” “The Stereoscopic Man Watches It Came From Outer Space In 3-D.” It is, in fact, this final activity which seems to give the Stereoscopic Man some closure about his identity, reflecting another key idea of the text—that popular media is not simply a means of distraction, but a tool for self-discovery. The Stereoscopic Man ends his journey secure in his multiple selves (“I am we”) and anchored in a spirituality that mirrors his own duplicated experience. “This is how he came to believe / in God in God.”

The speaker of the rest of the collection seems to share this acceptance of her multiple selves, but in place of god she has anchored herself in grief. The death of her parents sounds as a refrain, yanking the collection out of the fantasy of magic shows and Hollywood, reminding us that reality waits on the other side of the theater doors. “Listen / to how quiet it is when I lose the self-doubt played / for so long I mistook it for music,” says this speaker, to whom we return to after more than one stop with Marlene Dietrich. Functioning not so much as vocal foil but persona, Dietrich appears three times in Beer’s collection. The poem “Marlene Dietrich Plays Her Musical Saw for the Troops, 1944” instructs the reader to:

Observe how that polished body curves

in the strategy of lights, how its voice

is like a parody of mourning,

and so even more mournful

immersed in its high-pitched joke.

These lines encapsulate the manner in which the speaker of this collection confronts grief—with biting, bloody humor. “Because my grief was a tree,” titles one later poem in the collection, “I forgave the dog that pissed on it,” answers the poem’s opening line. Without losing her sharpened edge, the speaker drops her gruff façade in moments of intimate confession, as in the poem “The Poet Who Does Not Believe in Ghosts.” Here, the lies in which the collection has been rooted fade into the background and a cold, hard truth dominates: “the branch tapping against the window / is a branch tapping against the window.” In the spirit of Gertrude Stein’s “Rose is a rose is a rose,” Beer names death as death, as:

God’s apology

for suffering

a promise that the deepest human pain

will never be eternal.

Coping with the death of both parents, the speaker of this collection sighs in relief to know that “she is completely unnecessary / to her beloved dead,” that “… her mother her father are not / disturbing the genealogies of attic dust,” “they do not need her to solve anything.”