Each a Mirror of the Other: On Michelle de Kretser's "Scary Monsters"

Michelle de Kretser | Scary Monsters: A Novel in Two Parts | Catapult | 2022 | 288 Pages

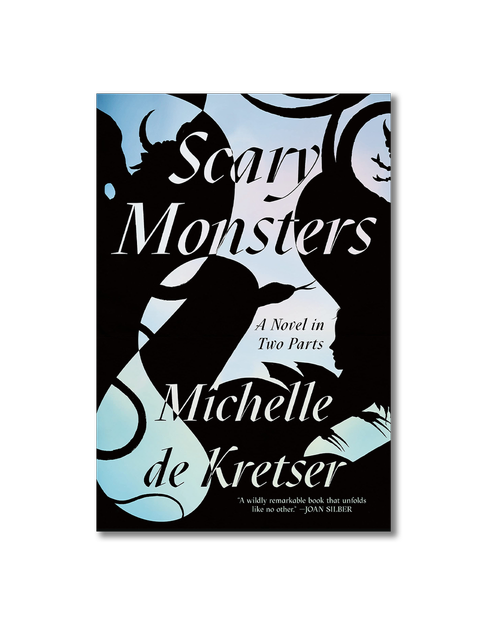

Scary Monsters by Australian author Michelle de Kretser begins with a choice. Not a character’s choice, but the reader’s: from which of the two front covers will you begin? With “Lili” or “Lyle”? Each story is 126 pages long, starts with the same two epigraphs (W.E.B. DuBois and Nietzsche), and meets in the middle at the author’s bio. The two halves of Scary Monsters could be read as their own novellas, but are meant to be read together: it’s the order that can be flipped on its head. Between these two narratives a gap arises between the future and past, the two different time periods in which the stories are set. Within this space, a pointed—and smart, and funny—indictment of our present social order reverberates, forcing the reader to consider how it refuses or admits people based on race, gender, age, and immigration status.

I left my choice of where to start to chance and landed on Lili’s half. Her story is set in France in 1981, in contrast to Lyle’s dystopian future Australia. I would have started with “Lili” anyway; I’m fond of female protagonists and realism. Lili narrates in first-person, remembering the year she was 22 and moved from Australia to Montpellier, France to teach at an English-language school. Seven years before, her family had immigrated from Asia to Australia, a first immigration that informs her experience of being brown and foreign in white, Western countries. Lili is attuned to the harsh treatment of North Africans in France and the casual way her white colleagues overlook their own privilege. World War II is still fresh on Europeans’ minds, which makes her wonder “why some people had history and other people had lives.” The Algerians, for example, aren’t considered refugees from French colonialism and the Algerian War but men after French women’s money. Lili struggles to find an apartment in the centre historique before realizing that even the “shuddering over cobblestones… belong[s] to Flaubert.”

Flaubert is a man, so Lili looks elsewhere to discover how to become a “Bold, Intelligent Woman.” At first she channels Simone de Beauvoir, but de Beauvoir doesn’t provide guidance on how to deal with the everyday threats of being female (in The Prime of Life, she calls worry of rape a “spinsterish obsession”). The newspapers seem full of accounts of murdered women, and Lili’s downstairs neighbor is hovering and creepy. Instead, Lili observes the possibilities in the lives of her female friends. Her friendship with Minna—another young woman trying to figure herself out—is recounted with nostalgia: they strike out on adventures and form one of those early adult bonds that seems like it’ll last forever. Lili does have her suspicions about Minna’s intentions in forming the friendship (is it because of her race?), but never broaches the subject. An irony, perhaps, as it is also Minna who teaches Lili how to take up the space that is hers.

Behind the second front cover, “Lyle” seems to depict a harsher place. Kretser’s future Australia has denied the realities of climate change to the point that the country has become uninhabitable and its citizens are repatriated if they so much as mention it. Surveillance is a state institution, and the state is corporatized. Like Lili, Lyle immigrated to Australia. Unlike her, he is an expectant parent hoping to give his children a life of opportunity. Lyle aligns himself completely with his new reality: “I understood that the past was no longer a reliable guide to the future.” He questions, “What comes first, the future or the past?” Denying the past is how Lyle copes with the realities of being an immigrant. When he and his wife move to Australia, they change their names and live in the suburbs, every characteristic and action weighed for how it might make them “more Australian.”

One could suppose that the extreme conditions of this dystopian future are what cause Lyle to deny his origins, but Lili shares some of these same qualities. Lili’s home country is also never named; only Asia is mentioned. This continuity between characters highlights parallels between the future and past. Without this parallel, it would be tempting to say that “Lyle” operates as Kretser’s warning for where our racist, ageist, misogynistic society is heading. But in Scary Monsters, Ketser is doing something more interesting than the typical dystopian indictment of our ills. With “Lyle” and the future on the other side, “Lili” and the past become dystopian as well. The bureaucracy of the French government that decides who gets a visa or not is a mirror of the bureaucracy of the future Australian government deciding who gets repatriated or not. The threat of sexual violence always hovering around Lili is similar to the many threats always hovering around Lyle, from the government to climate change. In other words, the only reason why the past isn’t labeled “dystopia” is because it is history.

The most quotable line from Scary Monsters is: “When my family emigrated it felt as if we’d been stood on our head.” This action becomes literal when one must turn the book around to read the other story, flipping Lili or Lyle on their head. The past and future mix. The experience of reading the two stories turns from parallel to a diffusion of boundaries. Take the two endings: “Lili” closes with youth celebrating, holding up lighters with flames that look like white blossoms; “Lyle” with a story his mother used to tell him where white blossoms are confused for murdered brides. Each ends with an image that is an inverted gesture toward the opposite’s cover. In the past, we can always look to the future with hope; in the future, we can always remember the past with nostalgia. But these two modes of seeing also act as blinders. In Scary Monsters, Kretser encourages us to look at both more clearly. Doing so, we hope, will keep our own monsters at bay.