Make It News: On Chris Marker’s “Eternal Current Events”

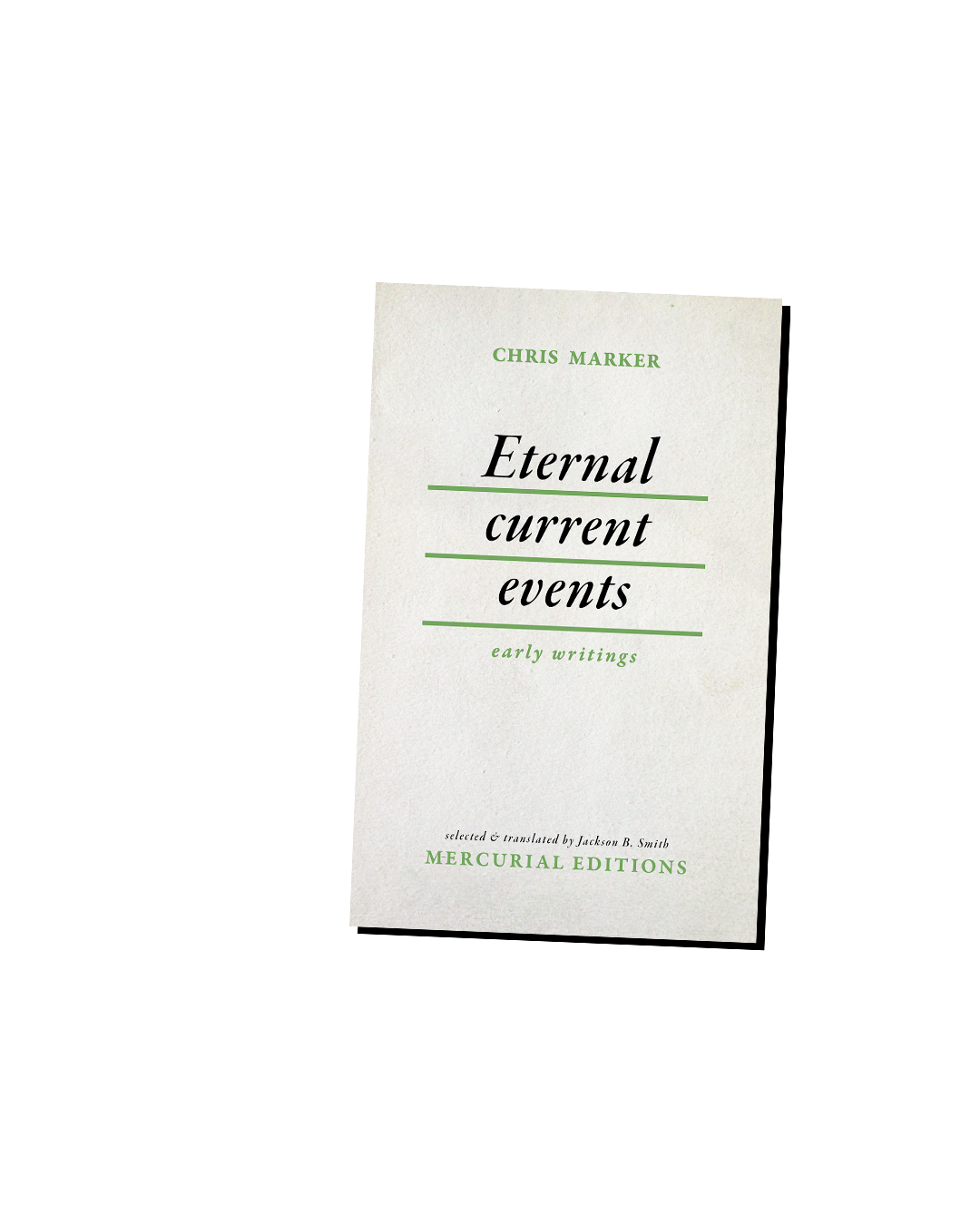

Chris Marker, transl. Roberta de Saint-Loup/Jackson B. Smith | Eternal Current Events | Inpatient Press | April 2024 | 120 Pages

On October 23, 2023, two undergraduate students at Northwestern University distributed alternative front pages to the campus paper The Daily Northwestern, with a “nameplate that read ‘The Northwestern Daily’ in a font resembling The Daily’s masthead.” This front page’s headline declared “Northwestern complicit in genocide of Palestinians,” mimicking the student paper’s medium with a message it otherwise refused to print. This alternative headline presents a blatant fact, but one that has been treated as a falsehood by the majority of media organizations. That the students could have faced a year in prison suggests that the news is serious business; that they were charged with “theft of advertising services,” suggests that the news is business, serious or not. Those charges were eventually dropped, but The Northwestern Daily’s presentation of truth in the form of a false newspaper sits within a longer tradition of art and activism that presents current events in a new light, raising questions about the lines between truth and falsity, art and activism, and the role of media in shaping what we know about reality.

Chris Marker spent his career playing with the lines between fact and fiction. Known by many pseudonyms (of which Marker was only the most prominent), he worked as a filmmaker, novelist, poet, and visual artist across the second half of the twentieth century. Rarely making public appearances, Marker voraciously documented mass political movements from the sixties onward, and his interest in artifice was not an attempt to show the falsity of political life but rather an attempt to capture how things that seem unreal might nevertheless shape what we call reality. In the process, he teaches us how certain events, feelings, or movements become treated as false, outside the bounds of what gets reported as fact.

Eternal Current Events collects and translates into English a selection of Marker’s early writing for the magazine Esprit between 1946 and 1952. The book’s first entry details a trusty dog, Oxyde, who refuses to eat bread that “underwent a number of modifications required by the government.” Yet Oxyde, like most dogs, “does not read the newspaper, he never goes out: the observation could therefore only come from him.” This small change from most consumers only knowing what is reported to them becomes a meditation on the role of news in coloring experience, and what knowledge never seems fit to print.

Marker’s most well-known films, Sans soleil and La Jetée, extended this interest in fact and fiction as an inquiry into the nature of memory. But in an earlier work, A Grin Without a Cat (1977; French title: Le fond de l'air est rouge), Marker captures the ebb and flow of global leftist movements in the late sixties and early seventies in a four-hour film essay (later edited down to a slim three). The film’s title, differently in both English and French, plays with the contradictions between substance and appearance, between fact and feeling, and Marker produces the kind of wide-ranging video essay that would eventually find popularity in the work of Adam Curtis. Through his own footage, archival documentation, and his trademark poetic voiceovers, Marker evokes not just the historical figures and major events of this period but also the way that this moment felt: the hope, cynicism, and fear that shaped twentieth-century revolutions, their possibilities and their falterings. Marker’s work shows that history is too open-ended to call it their failures.

Eternal Current Events allows English-language readers to appreciate the longer trajectory of Marker’s meditations on the vagaries of history and memory, the cruel ironies of political commitment, and power of feeling and belief. In the late 1940s, Marker began working with Travail et Culture and Peuple et Culture, “two organizations dedicated to popular education and the dissemination of culture,” according to Catherine Lupton, in her book Chris Marker: Memories of the Future. These organizations neighbored the offices of Esprit and the publisher Editions de Seuil. Marker became part of a group of artists and activists who worked in and around these various institutions.

Marker’s background, then, was not in the art world but in travel writing and the politically engaged popular and educational press. He saw that artistry was integral even to accessible education projects and to news and magazine writing. This space afforded him what Lupton describes as a “permeability to the influence of other media” and an “interest in transposing conventions and techniques across media.” Even at their most abstract and strange, his films maintain a connection to the everyday world, however tenuous; they often take the form of educational documentaries rather than arthouse cinema. His foray into science fiction, La Jetée, consists almost entirely of still photographs. Rather than special effects, his diligent attention to the minutiae of everyday life crafts an expansive imagination of a future. Marker explodes and explores these tiny details, finding whole worlds in a passing glance or a chance encounter.

This relationship between fleeting experience and the expansiveness of reality characterizes the enigmatic statement that opens this new collection’s title essay, “Eternal Current Events.” Marker writes, “We sometimes have the calming feeling that the real defeats the imagination armed only with its own resources.” The real and the imagination are locked in combat for Marker, yet what this real is—either the stories of established fact or the hidden truth of the world—he leaves open to discovery.

Journalism promises to write the “first draft of history,” yet this story requires a thorough fact-checking for writers like Marker. The news’s troubled relationship to fact and fiction has a history almost as long as the news. In one famous instance, the eighteenth-century British paper the Spectator deployed the voice of a fictional “Mr. Spectator” to relay details of everyday British life, and it adopted the printed form and feel of a newspaper while professing that it “has not in it a single Word of News.” The Spectator captured something current, even as its events were more often fabricated than reported. This early paper embodies the ironic, humorous stance that shapes much satirical news from the eighteenth century onward, through Mark Twain’s California journalism that display, in one critic’s words, a certain “laxity with fact,” to the now irritatingly common satirical news sites such as The Onion (originally a paper) or, on the right, the Babylon Bee. In the first episode of his satirical news show The Colbert Report, Stephen Colbert introduced the term “truthiness.” In his brash mock-conservative persona, Colbert urges the nation to feel with their heart rather than “think with their head,” all the while betraying the idiocy of such a stance, as he signs off with a promise to “feel the news at you.” Truthiness names one way to imagine the role of feeling, emotion, and ideology in constructing something so seemingly objective as a “fact,” yet Colbert hardly exhausts the possibility of inventive and imaginative news reporting.

Across this scattershot and admittedly anglophone history, the news has an intimacy with fiction, but such experimentation is not always fun or humorous. Since Orson Welles terrified those who mistook his 1938 radio production of H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds as fact, such panics have been the result of both purposeful and inadvertent manipulations of news media. On September 27, 1952, The Buffalo Evening News printed the headline, “A-BOMB DESTROYS DOWNTOWN BUFFALO; 40,000 KILLED.” Of course, Buffalo has never been nuked, and the false headline was masterminded by Lt. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner to prepare civilians for the growing likelihood of such nuclear devastation. At one point, the government relished the opportunity to present mass death as a headline, yet today student activists struggle to get that message into print, even when it’s an all too real fact of our present.

While the accusation of fake news is common today, the news’s mixture of fact and fiction has served a variety of political uses just across its anglophone history. In Marker’s France, his experiments for Esprit resemble the earlier writings of the anarchist writer, editor, and translator Félix Fénéon, whose Nouvelles en trois lignes Lucy Sante has translated for NYRB Classics. The word “nouvelles,” in the title of Fénéon’s running column in the newspaper Le Matin, translates into both “the news” and “novellas,” and the short entries use their scant detail to evoke the life the news so often leaves out. In one entry, “A 16-year-old of Toulon told the police commissioner that she had killed her newborn. He immediately put her in jail.” The frustrating lack of motivation and detail suggests the desperation that textures ordinary life.

In Sante’s words, Fénéon wrote at a moment when the newspaper “ruled daily life,” and its central status led to a variety of artistic incorporations and reworkings of the news format, such as James Joyce’s “Aeolus” section in Ulysses or Tristan Tzara’s method for making a Dadaist poem by cutting up newspaper articles, which would inspire William S. Burroughs’s cut-up method. What distinguishes Fénéon and Marker from this lineage of literary experimentation is their decision not to deconstruct the news and incorporate it in their work but to embed their work in the news itself. For these writers, fiction and poetry are not the news’s opponents but they are one way that news might circulate more vividly and achieve new political ends.

Marker’s May 1947 poem “Newsreel” echoes Fénéon’s nouvelles while playing with a variety of additional forms. The poem’s refrain, “the price of life,” introduces various scenes of quiet desperation that disrupt the rest of contemporary life:

The price of life. 1… - Because she couldn’t find a place to live, a young married woman throws herself into the Scarpe River.

DO YOU

HAVE AN ATOMIC FUTURE?

on the island of Peloliu

in the eastern Philippines

there is still a group of Japanese soldiers

ignorant of the outcome of the war

who continue to resist the Americans

The price of life. 2 - Because she had taken a false oath, a high school girl from Sèvres threw herself into the Seine.

What do two drowned women have to do with atomic futures or these rogue soldiers, ignorant of history, in the Philippines? The poem’s title “Newsreel” suggests that the discontinuity is part of the point. The poem takes the form of a montage, letting various stories sit together without being crammed into the same “story.” Marker’s enjambment of scenes and scales suggests that the constellation of these disparate examples becomes the only way to account for something like the news.

The poem’s final line simply reads “The price of life. 8 - In Greece…,” a country at the time locked in a yearslong destructive Civil War between the royalist government and a provisional democratic government, which partly arose from resistance forces established during Nazi occupation of the country. The vagueness of the line, though, clashes with the poem’s other mention of Greece, “The King of Greece died of thrombosis. He is replaced by his brother, the successor.” The line is strange, both in its mixture of obvious detail (the king is succeeded by his successor) with the unnecessary specificity of his death by thrombosis. “Newsreel” plays with the differential value of lives, as the poor drowned women seem un-newsworthy while the dead King of Greece seems obviously so. But this line’s passive verbiage—“is replaced by”—points out that the King’s inhabitation of his title leads to his own ultimate replaceability. Even the King is subject to his own endless succession, at least until we build a world without monarchy, social division, and the inequality that makes some lives valuable at the expense of others. That this world was being fought for “in Greece…” ends Marker’s newsreel with an image of cautious hope.

This crafting of social transformation out of ordinary life characterizes a February 1957 series of three linked entries, “The Skinny Cows,” “The Fat Cows,” and “The Medium Cows.” The first two sections detail various instances of police brutality, directed at poor and Black people in both Algiers and Paris, but in the last entry, Marker breaks into a prayer:

My God, who created cops, we are no longer in a position to be surprised by the curiosities of your Creation. But then give us the courage to refuse all complicity with them, and to love their victims…. Make it so that the world over, every man, whatever his fault may be, who is in the hands of the police, touch our hearts, and that it in some way it be we who are beaten. It will be one of the last forms of fraternity, while we wait for it to be the only one. Amen.

For Marker, it is not enough to detail the everyday violence of the police and the way it affects those he sees. To capture the way that cops have ruined the world, he must question the very extent of God’s Creation. He does not promote any empty reform but rather extends his prayer into a kind of apocalyptic vision of the utmost form of solidarity that dissolves every other kind of fraternity.

Marker sees the future in collectives. The ways that life forms itself in the present points to future ways that we might organize our society and ourselves. But it is not just through togetherness but also solitude that these future collectives appear. In a 1948 entry, “On Jazz Considered as a Prophecy,” Marker writes of sitting in a Conservatory hall, “almost alone… It was truly a pity.” But rather than see the nearly empty room, Marker instead explores the forces that “held back most of the event’s listeners in the making.” There is no such thing as an empty room, just one that has not yet been filled. But such future collectives are hindered by inequality, violence, and bigotry; Marker finds in jazz songs “complexity, a science that goes far beyond the simple rhythmic element to which European ears reduce them.” Combining generations of musicology with histories of enslavement and colonialism, Marker charts a history of an art form as well as the way so many white listeners have refused to hear it. And when white audiences and musicians have engaged with it, they have “made it their task to dispossess the blacks, and to convert the vague hodgepodge of boom-boom and tra-la-la that they pulled from it into double-zoons…even if that means distorting the very idea of jazz for an entire generation.” To fully comprehend jazz’s place as “the prolegomena to future music,” Marker suggests that we need to fully reassess art’s relationship to society: “Art can no longer offer any response to this harsh and fragile world, subjugated by all its forces and prodigiously the master of its destruction, except by denying it…. There remains jazz for expressing with certainty the order, the torn-up forms, the color, and the screams.” The denial of the world does not involve uncertainty. For Marker, that denial is often the only route to a certain vision of the world we will collectively build.

To evoke something other than our harsh and fragile world, some of Marker’s Esprit pieces are not reportage but fiction. In one story, “The Living and The Dead,” the archangel Gabriel joins and assists some residents of an unnamed French city occupied by an unnamed enemy army. Such an occupation resembled Paris not long before Marker wrote this story in May 1946, and the various people discuss their means of surviving in such a state. “We don’t know how to take advantage of life,” one character, Christel, pronounces, “There should be traveling salesmen who go door-to-door telling people that Joy exists, and the proof is that we’ve got music all around us. People always believe what’s been printed!” The printed paper is a source of authority; it tells people what to believe, even the basic facts of their reality. Christel’s salesman of Joy at once presents an absurd solution while imagining the compassionate ends to which those writing the news might put their current events.

Marker’s lesson, in part, is that the news is what you make it, but you cannot make it just as you please. His documentaries of social movements—from Grin Without a Cat, documenting the global turmoil of the sixties and seventies, to his late documentary The Case of the Grinning Cat, which found echoes of that earlier moment in early twenty-first-century demonstrations in Paris—are all stories of the capacities for mass movements to transform the world. The point of Marker’s intervention into news media is not that facts are mere socially constructed fictions; rather, with enough collective action, we might change fact itself. His imagined current events point toward these moments when we might collectively push on the bounds of reality and transform it into something better.

This was, I think, part of Marker’s draw to his endless list of pseudonyms. The translator of Eternal Current Events lists some of them: “He is Jacopo Berenzi, Marc Dornier, Sandor and Michel Krasna, Fritz Markassin, Jacopo Nizi, T.T. Toukanov, and Hayao Yamaneko.” This list also precedes an excerpt of this book in The Baffler, with the translation credited to Jackson B. Smith, whose name also appears on the Inpatient Press website. However, the review PDF from which I am writing this essay states “Translation by Roberta de Saint-Loup.” Whereas Smith has a website, the internet has no trace of Ms. Saint-Loup. Is the name a reference to the character Robert de Saint-Loup in Proust’s Swann’s Way, or has Roberta taken the reins from this earlier translator? We have likely found ourselves in another maze of alter egos. Perhaps, as with Marker’s own name, there are certain truths that can only be written by someone who does not—or does not yet—exist.