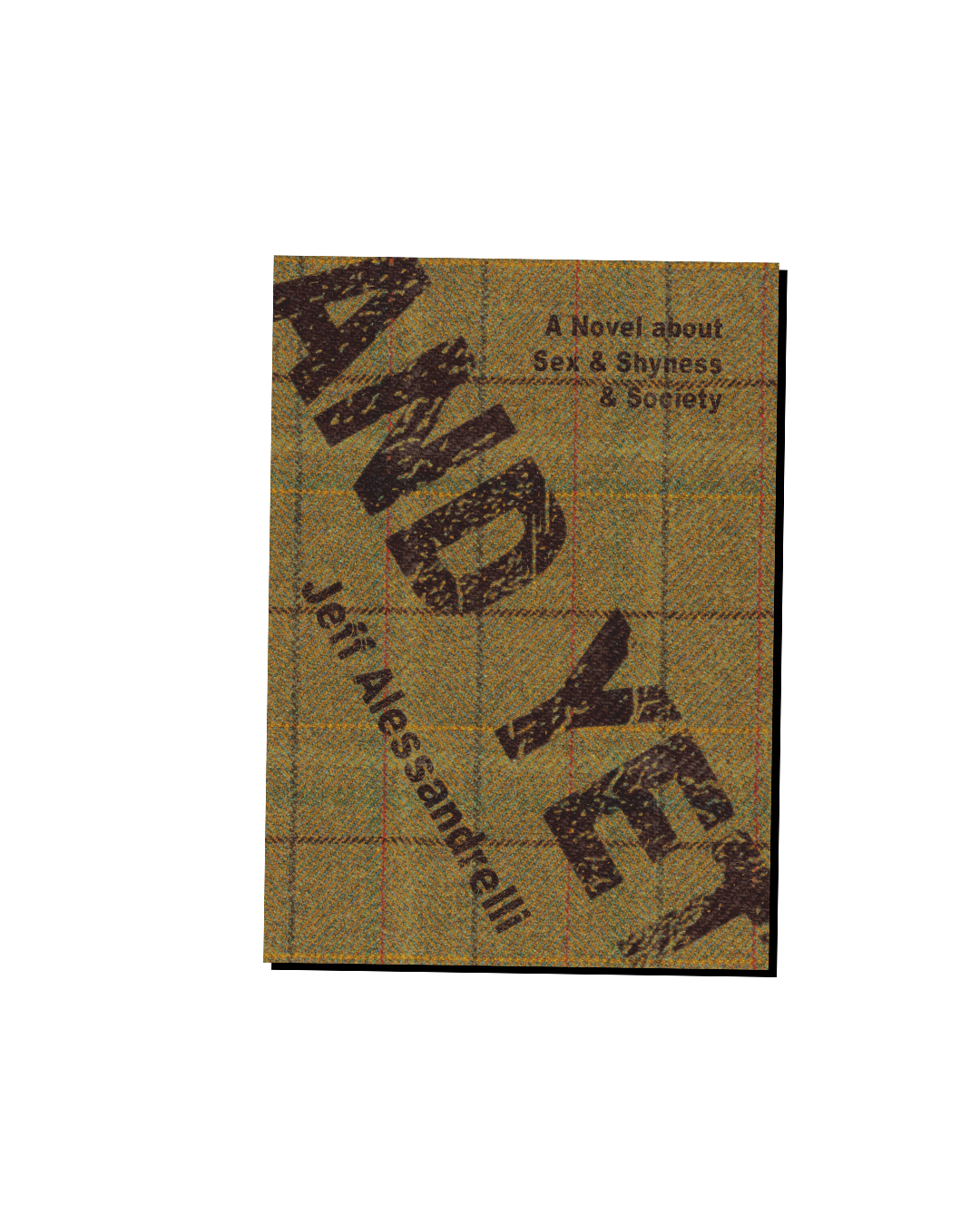

from "And Yet"

Jeff Alessandrelli | And Yet | Future Tense Books | 2024 | 252 Pages

More desirous of personal understanding, identity and security, Millennials become sexually active later in life and sleep with fewer people than their generational predecessors did, but conversely (and perhaps surprisingly) male Millennials are more prone to stereotypical masculinist attitudes than male members of the Baby Boomers or Generation X were. Titled “On Gender Differences, No Consensus on Nature vs Nurture” and using as its tagline the statement “Americans say society places a higher premium on masculinity than femininity,” a 2017 Pew Research Center survey details how “Millennial men are far more likely than those in older generations to say men face pressure to throw a punch if provoked, join in when others talk about women in a sexual way, and have many sexual partners.” The survey further discusses how, although only 24% of male Millennials classify themselves as “very masculine,” many men of the Millennial generation nonetheless accord masculinity (and all its attendant attitudes and behaviors) substantial weight in their lives, with 82% of all men in the Millennial generation describing themselves as masculine to one degree or another, and just 18% abstaining from using the term as a self-descriptor.

*

It didn’t cover male Millennials seeking or undergoing talk-therapy treatment, the “On Gender Differences” Pew survey, but by virtue of the minimalizing of forthright emotion that burrowing in one’s masculinity can often beget, it has to be assumed that talking to a therapist isn’t, for at least some substantial swath of men in the Millennial generation, the immediate go-to solution for mental health concerns. (As with everything, the Internet can tell you more if you’re interested. Although their individual takes might be debatable, a quick Google search elicits articles with titles such as “Why Millennial Men Don’t Go to Therapy: The most depressed generation won’t get help despite having more access than ever before” and “Millennials are facing a mental health crisis, and it was entirely preventable.”)

*

At the end of “Car Crash While Hitchhiking,” the first story in Denis Johnson’s famed short story collection Jesus’ Son, the unnamed narrator, involved in the deathly crash but completely unscathed, tells a doctor imploring him to get checked out: “There’s nothing wrong with me.’” Thinking back on the moment later, he relates, “There’s nothing wrong with me”—I’m surprised I let those words out. But it’s always been my tendency to lie to doctors, as if good health consisted only of the ability to fool them.”

Most patients aren’t in as dire straits as the narrator of “Car Crash While Hitchhiking,” no. But due to embarrassment or fear of being judged, lying to one’s doctor is prevalent in Western society. To be clear, these are often white lies, not life-threatening ones. Still, a white lie is a half-truth is a real fib.

*

Different than some of my male peers, I’d sought out therapy twice before in my life, at the ages of twenty-five and twenty-seven. Both times I’d found the experience frustrating. I’d talked, I’d listened, had worked on Rational Self-Management and the immediate recognizing and harnessing of my Automatic Negative Thoughts. Even so, nothing had really changed. Only talking to my therapists for a total of three hours a month and seeing each for, at most, four months at a time before abandoning everything hadn’t helped. That’s like trying to cure a migraine by wrapping an Ace bandage tightly around your head and thinking happy, peaceful, anti-migraine thoughts is how my friend V once described my therapeutic experience to me in an email. You’re not really doing anything and don’t sound like you really want to do anything but by telling your therapist that you want to try you’re trying to tell yourself. It sounds like a sort of lie V wrote. Her mother having abandoned her family when she was three before later committing suicide when V was eight, V herself had been in therapy for years, with considerable success. If you’re willing, it can be there for you. But it’s up to you, not the therapist.

*

XIV. The easy attainment of love makes it of little value; difficulty of attainment makes it prized.

*

From the diaries of renowned Italian poet Cesare Pavese—25th December, 1937:

There is something sadder than growing old—remaining a child.

*

Back then I’d told my therapists I was insecure and left it at that. True, but only partway.

*

Older now and still searching, I aimed to lay it out, to not lie at all nor (consciously at least) self-aggrandize. Prudently or not, my guide here was the monologist Spalding Gray, whose work I’d discovered early in my Midwestern sojourn and found revelatory for its insistence on interrogation and unvarnished directness of self.

*

Perishing by suicide in January 2004, in December 1985 Spalding Gray wrote:

“The whole process of writing… has been very healing, to the extent that it has projected into me a future. And although this cannot fully assure a future, it has at least created one for me to move toward, as I watch it race ahead before me.”

*

And yet.

*

The first two therapists I found online, Googling “Blue Cross Blue Shield talk therapy coverage (sexuality self-esteem relationships).” The last I found by recommendation of a friend of a friend.

*

Both bespectacled married middle-aged straight white men from Missouri, it is hard for me now to differentiate between those first two. Ted was #1, Steve was #2. Ted had slightly receding dusky blond hair, a penchant for wearing Crocs with socks, and a genial disposition that simultaneously soothed and irked me. Hair colored dusky blond also, Steve had a starchy crewcut gracelessly aspiring to fauxhawk, a penchant for wearing dark green V-neck sweaters, and a genial disposition that simultaneously soothed and irked me.

*

I laid it out as truthfully as possible, or at least tried to. I told TedSteve that I’d been celibate for a year and nine months, willfully for the first year but not for the last nine months. I told them that during that period I’d isolated myself and was very lonely. I told them that I didn’t much care for the Midwest and how once I finished school I planned on leaving the area forever. I told them that I loved my family, my parents and younger brother, but felt somewhat distant from them emotionally. I told them that with new romantic partners I was always initially shy sexually, a so-called prude, and that sometimes that shyness overwhelmed my sense of sexual self both in the moment and down the line, months or even years later. I told them that, so far as I understood the word, I’d only been in love once, that it had been years ago, with a woman who broke up with me for someone older and more successful than me. I told them that, despite my intimacy issues or whatever you want to call them, I’d slept with multiple women, more, actually, than the national average for a man my age (did they by chance know the national average for a man my age?), and, in terms of prowess and proficiency, felt I was a serviceable lover, if somewhat unadventurous. I told them I wouldn’t mind seeking out said adventure but wasn’t sure, within the confines of my own present sexual machinery, how to do so. Spurious façade, I told them that I thought masculinity was a sham, but one I nevertheless felt inclined to live in. (Why? Is it because I was so afraid of my masculinity that I felt intoxicated by that fear?) I told them that going down on a woman sometimes felt shameful because it aroused me to such a degree, that I occasionally hesitated to do so because of my blood-red desire. I told them that even if I wasn’t sure who I was from moment to moment, day to day, I often absorbedly lived inside my head to a probably unhealthy extent, and that this self-absorption seemed to be, for an aspiring writer at least, both problem and solution. I told them that the concept of lust as grief seemed to be a silly one to me. Walking back from the bar alone or driving my car next to the dense green empty cornfields everywhere around me, I couldn’t help but believe in it nevertheless.

I told them that I loved to read but felt that sometimes I used this love as a way to mask my own personal feelings, sentiments and beliefs—repurposing the words and articulations of others as proxies or stand-ins for my own. I told them I had a robust scope of imagination, which both helped and hindered me. I told them I drank too much water and too much alcohol and that the former was contributing to my constant-micturition issues and the latter my depression. I told them that learning was important to me, perhaps the most important thing to me, but that with regards to academic learning specifically (at this point I’d been in the higher education system for nearly eight years, B.A. to M.A. to PHD) it was no doubt holding me back vis-à-vis the many societal fundaments and directives embedded in “the real world” that I still wasn’t aware of or privy to. I told them if I was being honest with myself I tended to run from my problems rather than face them, that I moved around a lot as a result of this, that my geographical wanderlust no doubt had personal consequences for me. I told them that I was a very lucky person, incredibly privileged, and that I regularly forgot about this fact or downplayed it. I told them that the possibility of the private past becoming the public present scared and titillated me. I told them, repeatingly, above all else, that with so much “stuff” out there I wondered where my own “stuff” might one day soon or far fit in, and how a monastic life of quiet reflection seemed ideal and impossible to me. I told them that I felt like I was living inside a box of my own creation and that, although initially I had welcomed this, even luxuriated in it, now it felt like a trap. A la Spalding Gray I sometimes gesticulated wildly while conferring all of the above to TedSteve. At other times I stared at TedSteve’s benignly shuffling feet or into TedSteve’s four slowly blinking eyes.

*

Terminally unique, forever, shining star shining bright.

*

From the diaries of Cesare Pavese—29th August, 1944:

Only uniqueness justifies…the absolute value which puts us above all contingencies.

*

Perfect necessity. Eternally true.

*

TedSteve listened intently and took notes. They then asked me to do certain things: keep a gratitude journal; make a point of approaching one new person (man or woman) every day in order to start a casual, risk-free conversation with them. Take the time to identify my triggers (sexual and social) and, having done so, sort through each in the moment, thus allowing my (best) self the freedom to be who it could be without fear of personal persecution or censure. They asked me to conduct a daily mental inventory. Using transactional analysis, each worked with me on furthering my notions of personal autonomy and awareness.

At my request, TedSteve also recommended three books to me, Sex Is Not a Natural Act and Other Essays (1995) by Leonore Tiefer, Neurosis and Human Growth: The Struggle Toward Self-Realization (1950) by Karen Horney and Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection (2008) by John T. Cacioppo and William Patrick.

*

Although some of its Clinton Presidency era talking points now read a bit dated (the book was initially published in 1995, with a second edition coming out in 2004) and sentences such as “To understand sexual excitement, for example, you need to understand how psychology, biology and society interact and change” might stultify even potentially interested readers, psychiatrist and sex therapist Leonore Tiefer’s Sex Is Not a Natural Act and Other Essays was illuminating for me to encounter. Tiefer’s primary concern in the book is with the social and cultural construction of sex; how our every understanding and insight of it has less to do with ancient biology and more to do with present day society. Sexual normality derives its purchase from the need for social conformity, and Sex Is Not A Natural Act takes its title from cultural theorist Raymond Williams’s assertion that the word nature “is perhaps the most complex word in the [English] language.” Every thought of It’s totally natural to want to [fuck your beautiful girlfriend /fuck your handsome boyfriend/ fight your worst enemy/ sleep until noon after a hard day’s work/ dance naked at dawn on summer solstice/ ad infinitum] deals, at its core, far more with social construction than any reasonable definition of naturality. In Tiefer’s words, “Belief that sexuality comes naturally relieves our responsibility to acquire knowledge and make choices.” She goes on to state:

“Natural sex, like a natural brassiere, is a contradiction in terms. The human sex act is a product of individual personalities, skills, and the scripts of our times. Like a brassiere, it shapes nature to something designed by human purposes and reflecting current fashion.”

*

When asked if he worked from nature, meaning studying the world as represented in immaculately spruced trees and concentric pears and oranges in similarly concentric bowls, Jackson Pollock famously replied, “I am nature.” What gets forgotten, however, is that it was the older artist Hans Hoffman—an Abstract Expressionist pioneer in his own right—who did the asking and, on hearing Pollock’s reply, retorted, “You don’t work from nature, you work by heart. That’s no good. You will repeat yourself.”

Hoffman meant that, however natural a person or their art is, there’s no getting away from the self’s entanglement with society, that the more original one believes themselves to be the more they inevitably rely on ideas of originality that are tired and stale, unoriginal.

*

One of the standout tracks on their 1979 album Entertainment! (listed by Rolling Stone at #483 in their 2009 “The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time” article), UK post-punk band Gang of Four’s song “Natural’s Not in It” calls for a renunciation of commodified societal constructions like Love and Pleasure and Sex. All discordant incision, Gang of Four’s singer sing-shouts evocative enigmas like “The problem of leisure/ What to do for pleasure/ Ideal love a new purchase/ A market of the senses” and “Fornication makes you happy/ No escape from society/ Natural is not in it/ Your relations are of power” over jagged guitars and rapid-fire drum fills and breaks. Repeated six times, the chorus of “Natural’s Not in It” is the lonely mantra “Repackaged sex your interest.” The way Jon King, Gang of Four’s singer, intones it again and again the listener feels indicted by association: Who hasn’t had repackaged sex for mindless pleasure?

“The body is good business…This heaven gives me migraine” is how “Natural’s Not in It” ends. King sings the words emphatically, but beneath there’s a glimmer of indeterminacy. If humans can’t allow themselves what they’d like to believe is non-negotiable “human nature,” what are the consequences? There’s no escape from society and the self within it, and King shouts against the mirage of naturality in rhythmic bursts and gasps. If natural’s not in it, what is? Anything?

*

And yet.