The Precarious “North” of Jacques Darras

Jacques Darras, transl. Richard Sieburth | John Scotus Eriugena at Laon & Other Poems | World Poetry Books | 2022 | 152 Pages

“North is a precarious philosophy,” goes Jacques Darras’ poem, “Voyage to an Island Tongue.” Yes, one has read it before across the Anglo-European oeuvre: the oblivious north, with its unchristened snowy hovel towns and autodidactic screeds levied against southern kings and popes. Take Shakespeare: one might divine a pattern among his plays, whereupon the ones set in northerly reaches like Denmark and Scotland concede a certain dreary atmosphere prone to tragic delusion, whereas the plays set in Italy, Egypt, Athens, if somewhat illusory and inspirited, are given to comic levity and interpersonal dupery more than the stewing solipsism of Hamlet and Macbeth. In Darras’ catechetic epistle, “To Augustine: On Paradise,” this northerners’ umwelt is caricatured in asking, translated into practically-Shakespearean drollery, “Be it by scission or division, will we always have to play out the game of the melancholy Dane? It’s true that in these colder climes we tend to fold back into ourselves, to bundle ourselves up in the fur-lined mantels of our metaphysics, or lose ourselves in drink.” The tableau recalls a Nietzsche of The Joyful Wisdom maligning the good-hearted north, the inhabitants of which naïvely interpret words they believe unmediated by histories, by place, by influence. The south, the atticizing Mediterranean, however—these people understood the subtleties that mattered, understood how power operates, taking in their daily inhalations of dust from via Appia Antica. The Dying Gaul, triumphally exhibited in Rome’s Capitoline Museum, still wriggles, almost in collusion with the enemy.

Rebuffing the ages-old propaganda, Darras’ poems remain unconquered, even mostly without animosity, without the froideur of “North.” They reject the suddenness of metropolitan vanguardism with a prosaic inertia that one hesitates to call provincial—rather than react, “The cold preserves.” The poet’s native Picardy is, à la France, the deep north. A Parisian recently said about traveling to such French norths, “Why not just sojourn in England instead?” Darras’ “North” is, after all, a north in constant kinship with the United Kingdom, North Sea, Hebrides, Pieter de Hooch and Jacob van Ruisdael’s Holland. The poet is undeniably attempting to interpolate these spaces, his mention of northerly personages making for a kind of Hesiodic Ehoiai. The northerly asceticism suggested by Nietzsche is fraught with an eagerness to convalesce from world-historical malady, all at the ripple of a sentence. Island dwarfism, that spurious risk of a northerly poetic canon, is a nonissue. Yet Darras’ poetry does not invite distrait tourists or frolicking Parisian weekenders—after all, “North is a precarious philosophy.”

That “North” is here a philosophy in any measure goes a far way in ascertaining John Scotus Eriugena at Laon and Other Poems, a collection of Darras’ work, recently translated into English by Richard Sieburth and published by World Poetry Books. To follow the poet’s work closely here, one must not set off with the notion that his writings constitute a poetics of place, that the poetry merely adapts the topographies of terrestrial space for the written word as by the machinations of a cartographer—for it is the overflowing wordiness of what supposedly antecedes writing that is the matter. Place is already a poetics, and Darras and his poems are native transcribers of Picardy and its linguistic tactilities.

In the happy scur of color, space outdoes itself with a horizon of hills and peaks, sometimes appearing as an alternate version of matter.

An alternate version—a versification.

The isle, a natural poem—gratis.

A landscape poet’s intervention upon natura naturans this is not; rather, lands are already languaging. Several lines down the same “Voyage,” one is further instructed that isles may be “The finest of schools to learn the grammar of space.” It is on an isle, surrounded by the lapping of waves, that one may bear stark witness to the changeability of sedimentations, to the way formalistic lineaments reputing solid ground actually weather and wobble at the brinks of contingency. Between the isles “float a multiplicity of liquidities, syntactic elasticities.” The heave of the monostich, annotation, aphorism rises, crests, falls and rises anew, not unlike the lines of Wallace Stevens’ “Adagia.” What shapes up across the water columns of both poets is an advection full of subtidal currents. In considering this “precarious philosophy,” one cannot help but drift continentally back to Jacques Derrida’s footnote in Writing and Difference about the prose of Emmanuel Levinas across the latter’s Totality & Infinity: “It proceeds with the infinite insistence of waves on a beach: return and repetition, always, of the same wave against the same shore, in which, however, as each return recapitulates itself, it also infinitely renews and enriches itself.”

This repetitive activity of the wave is most immanent in “Sea Choirs of the Maye,” where the fluvial ease of Darras’ “Voyage” and “I Maye” succumbs to the permanent strophic oscillation of La Manche, the English Channel:

we shall never be done with the sea

we shall never be done

we shall never be done with the restless motion of the sea

we shall never be done

Yet the prosaic grammars moving in both poetry and philosophy will eventually divulge that the same is not the same, that “the sea is not the sea.” As dancer Pina Bausch said, “Repetition is not repetition.” Space and its predicates are always taking up the contingent residues of repetition, recording the cumuli of “restless motion” and declassifying what is, ultimately, the gambit of the identical return:

To return

To return

To return

To return

What returns with the sea is the illusion of return

What returns with the sea is the illusion of the movement

of the wave

This vatic poem transcribes a sea that “does not” and “shall never” commit to les objets trouvés of a phenomenal surface, inherent memory, allusive depth, repressive drive. Instead one reads an apophatic blanking of the sea’s palimpsestic slate. This ἀπόφανσις (apophansis) of the shoreline recalls Martin Heidegger’s unspooling of statement in Being and Time, wherein apophasis necessitates apophansis, necessitates declarative but deceptive indications. What the wave giveth, the wave taketh away. Nevertheless, just as Heidegger’s and Levinas’ prose, Darras’ poetry does not go in for a tidy economy of motion. It might then be fitting that, according to “Voyage,” the sea is nothing less than poetry proper, “An horizon of expectation” which takes its expectants “Always further out,” beckoning them “To steer an unreasonable course away from prose.” One is drawn out to sea or toward its edges, for it abounds in a lyrical entropy of traces and, in its congress with the prosaic shoreline, makes “illusion[s]” reemerge.

Such a recurrence of line-smudging waves in European poetry cannot be dislocated from the Dantean onde, which Henry Wadsworth Longfellow awkwardly yet provocatively forced into the position of the English locative, “whence,” folding difficult phenomena and “illusion” into placeness, into a matter of the wherefrom, just as does the bard of Picardy. Darras’ poetry may long for this alleged poetic horizon from which waves—and, indeed, shades—emanate but, in its subtle (if finless) wisdom, remains coastal, estuarial, riparian and mesopotamian, brackish but content to let lyric fall tame upon the sand. These thresholds compel a timorous poise, as before the “grey sand” of James Merrill’s “Accumulations of the Sea,” where one “Touches at last the sand, as one descending / The spiral staircase of association.” In this space between illusion and its place, epic waves and their tragic horizons, it is the grounded precarities and liminal footings that gain the poet’s and poetry’s favor, “So that, should Paradise exist for the poem, it shall only be / accessible in the stutter of an archipelago.”

•

It is difficult to avoid touching upon a common blunder in what I shall be non-too-pleased to identify as the dialectical complacency of dumb poetry, a contemporary devolution into sheer farce, where verses continue to snag themselves on such ham-fisted reifications as “Present / and absent, I / stand here.” Such sequences as the one precedingly confected are, of course, grotesques of poststructural thought. It is only when the sex appeal of liminality and other structures of so-called paradox confess a phenomenal discursivity that anything interesting can be borne out. This often necessitates the concurrence of or reasoned struggle with topoi, with distinctive themes. Darras’ poetry seems always to have known how to do this. Accordingly his poetry has always helped conduct conversazioni between philosophic and poetic modes, periods, eminent territorial features.

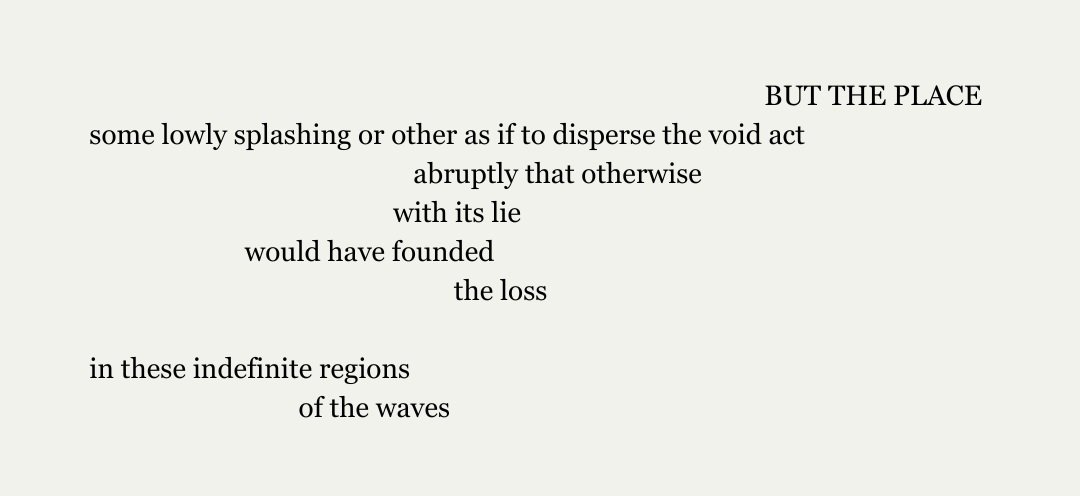

Archipelagos, for instance, bear an arresting felicity with erstwhile poetic modernisms, particularly those of the early twentieth century. Darras’ work has the reputation of having ignored the Mallarméan accident, the coup which, with some decisiveness, freed free verse from the stiff adjudication of linear type, among other things. Darras himself decries this so-called Mallarméan abstraction—as the translator, Sieburth, notes in the afterword—calling himself a “figurative” poet. This is, however, a hugely misleading bifurcation. The Picard poet takes up a commonplace critical schema right where poetry—his own poetry—is most disclosive and cogent about figuration and its would-be nemesis, abstraction. His poetry does not merely offer a sort of figurative simultanism or a making geographic of antiquarian time; it rather insists on an “alternate version of matter. / An alternate version—a versification.” Just as text undulates and lines flow, so too must lands and rivers and seas and archipelagos poeticize.

Stéphane Mallarmé’s urgent message, Un Coup de Dés jamais n’Abolira le Hasard—is it not streaked with tenuous archipelagos?—is it not given to make of space (blanked, empty or gently-oscillating space, if one must) the locus of meaning, the topos without the contingencies of which meaning would not form up? Alternatively, it may be so that Guillame Apollinaire, Mallarmé’s fellow, as is often and again repeated, painted with his verses—that his poetry was suffused by a retentive curiosity about figuration. If one grants to this critical trope all the philological stature it might erroneously desire, Apollinaire and Mallarmé iterate two wholly distinct if not antagonistic poetic paths. In traversing what is ultimately hereby a labyrinth, one might begin with the enquiring observation that Apollinaire’s lines in “Zone,” so itinerant and well-traveled, occasionally make Un Coup de Dés’ supposedly-freed words seem as though they are only ever at the page and nowhere else. Coming to terms with this apprehension is no small beer. Space and its grammars of relationality hang in the balance. Indeed, the telling difference between Mallarmé and Apollinaire is that the former omits “like” and “as.” Where Apollinaire writes, “You are like Lazarus stupefied by the day” (“Zone”) and “Love goes like this water flows” (“Mirabeau Bridge”), Mallarmé writes:

Mallarmé wanted to flatten the semiotic matrix—as convoked, say, by a signified and a signifier—and impress into space a kind of metaphrasing literalism about space, whereby words and letters admitted openly what they all along had been doing, as it were, behind the scenes: dancing, playing, acting, being, spatially existing.

Metaphoricity, in this case, was already built-in at the sub-particle level, already conceded by the plasticities of identity and signification. By this rubric, words carry intrinsic comparativity; the something-beside-somethings, the “like” and the “as,” were redundancies, even archaicisms. Meanwhile, Apollinaire was operating within the same problematic, though without the arbitrage and rhetoric of blankness. One could further argue that the cubist poet was taking words more seriously, that he determined their being already possessed by spatially-evocative properties and not in need of liberation. Even the “like” and the “as” had this claim to the materia poética of a poem, much in the way the line has a claim to the face, the copular detail or canvas-edge to the painting. A relationality of meanings need not be, as it were, exaggerated by concrete gestures and blanked space.

According to the Apollinaire logic, words, even “like” and “as,” do not require the constant attestation of physiological themes—a word which itself derives from an interest in, study or development of nature. Thus figuration, which criticism automatically places beside nature and naturalism, may very well be more properly attributed to poems of Mallarméan descent than those poetries which, like Darras’, might suppose filiality with Apollinaire. Darras’ collected poems do not press the distinction, but instead comprehend both Mallarmé and Apollinaire, both the material facticity of word-phenomena and the referential worlds of words. The difference is, after all, only as marked as the ink of criticism will permit. Apart from Darras-the-partisan, Darras’ poems seem to know that words are so possessed, bearing, as they do in “Voyage,” the language of topographies under the guise of mere docentship and cartography:

Isle/loch—a new syntax, fluid and solid, a new geography, a fresh revision of space.

Donne’s no man an island in need of Copernican revolution.

A new island, a future island, a break, a gap—space hence-forth unmoored from itself, be it by substance, form or trace.

Rips, angles, creases, hollows, edges, gulfs, crooks, rias, peninsulas, bays—all addressed to the same sense of touch.

To touch land while no longer touching land!

To touch land while losing touch!

These plots mark Darras’ archipelagic mediation between Mallarmé and Apollinaire, between the ink-and-wood pulp of word wavelengths and their indexical conventions. It is happening just offshore, where the waves thrum their salty ostinato. The supposedly staid phenomena of the printed page, as all forcible poetry lets on, dissimulates what is already happening: activity, motive energy, the actuations of being somewhere. One is brought along, tracing the nomenclature of the land, feeling the anaphoric deep-water swells beating at the hull.

•

Across even the most seafaring of the poems in this collection, the land is always legible; prose is always grammaticizing away from enthusiasm, back to Zarathustrian “edges, gulfs, crooks.” The precarity of this “North” philosophy lies in the poetry’s tendency toward aqueous uncontrollability, where coastal distinctions—the coastline—can be remade according to secret readings of little-tread-upon riverbanks, strands, nautical vantages. What persists is a tacit worry over an Icarian drowning. Most can catch a draft; few can land a vessel. As Jack Spicer’s “Any fool can get into an ocean…” puts it, “What’s true of oceans is true, of course, / Of labyrinths and poems. When you start swimming / Through riptide of rhythms and the metaphor’s seaweed / You need to be a good swimmer or a born Goddess / To get back out of them.”

Poetical encroachments upon other philosophies, as that of Levinas, are analogous to this perennial and hazardous dream of sail-setting and flight—lyric, furious, sea-bound and elsewise. What “Sea Choirs of the Maye” transcribes as “the illusion of the movement / of the wave” constitutes a consolidation of just this obsession. More mystified poetic discourses can linger here for ages, between the poetic statement and its putative negation, apprehending the shimmering footprint, agog at the skirts of seafoam. Pioneers hope to espy hints as to where precisely Oceanus’ mouth meets its tail. The more satisfying iterations of such poetry, while they toe at the swash zone, comprehend what the wave’s ἀπόφανσις leaves behind in remainder. It is what Paul Valéry sought by way of more established poetic geometries: a poetry so phenomenally immanent as to be indistinguishable from the jet of meaning, from the embrace of the already-interpreted (in Margins of Philosophy, Derrida contests that Valéry, in his religiosity about such jets and embraces, actually decried meaning, subordinating it as an excess that is nothing but interpretation).

Perceptible union with a subject matter was often famously the aim—this or a repristination of antiquity. Either way, an ode was often involved, as with the iconophilic reverence of city-dwelling Keats’ “Ode to a Grecian Urn,” where boughs, unlike in prototypes such as Shakespeare’s haunting Sonnet 73 or Ecclesiastes 1:5, “cannot shed,” “nor ever bid the Spring adieu.” The syncretistic and odic impulse reverberates through Symbolisme and English Romanticism, the culmination of which might reside in Shelley’s movement in “Ode to the West Wind,” from the “If” (“If I were… / a wave to pant beneath thy power”) to an importuning “Make” (“Make me thy lyre”) to the nefas of an obscene “Be,” where a possible union with Zephyrus makes for a dreamy clarity, an inhabiting of boundaryless nature (“Be thou, Spirit fierce, / My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one!”).

Unlike other so-called nature poetries, however, poetries like that of Darras do not attempt to solve the Sphynx’s riddle. They rather live amidst the language already sustained by things. Insofar as they puzzle all the same, Darras’ seaside poems nativize the asked question only to spread it across the sand. They become the liminoid Sphynx who waits at places of passage, places like those between the context of lyric poetry and that of sober prose, by becoming that creature’s third division, its end or beginning or middle. It is those who think themselves the isolated answerers of riddles posed who get hurt. The Irish “North” theologian and philosopher about whom Darras writes, “John Scotus Eriugena at Laon,” author of De Divisione Naturae, flies from his vessel, meeting “Hell” in a sphynxlike swoon. He had his “gaze wrenched from its angle / of purchase upon the world / capsized, head now careened / against the suddenness / of rock.” The poem suggests that one must admit of an inevitable risk in order that one not be thrown from his footing. That is, one must adapt to what, some way’s away, used to be called sphynxism or an ironistic evasiveness, possibly even conducted in mala fides. Where Darras’ poetry transcribes a coastline, either between sea and sand, an England and a Gallic France, a sweet death and tragic life: an endless trialogue, but one that rebuffs romanticism and Oedipal revelation. As sphynx, one must admit of his being already irrevocably mixed up with nature and its themes, as this precarious anagoge suggests in its Dantesque stridency:

the divisions of the world now

extended, now illuminated between the lines

the borders of the intangible now flaring up

with darkness, the granular opacities

now brightening, the sun biting into

the margins of the real, the image dying.

It is, however, where lyric ebbs at the land that the romantic cyphering is found most redundant. The onde waving about the wanderer, the revolutions of minutiae—here they redouble, treble. Lucretius’ or Heisenberg’s clinamen swerve everywhere in a quantal disintegration of the human-scale and its material patternings:

The beach this running wild is called poetry

The beach why do we always return to the poem

The beach because at the seashore the waves fold forward like

lines of verse

The beach because in the poem the lines roll in like the surf

…

matter happens

within its subtle atoms we happen

the invisible sea sough within our minds happens

our bodies torn between horizons happen

something happening at the limits of earth air water

the crossing of limits having always happened

Concrete at the left margin, “Sea Choirs” can read like a prosaic extrapolation of Aram Saroyan’s one-word poems: “lighght.” Waves riddle the grey sand with waves, wave after wave, altered wavily in their supposedly-incidental particularities.

•

Where most impressive, Darras’ poetic is interested in occupying the seat of enigma without succumbing to stupefaction. Everything in this “North” is subject to a granulose, intertidal and yet geological scale, beachward Prufrock’s abyssal and halfdead “ragged claws / Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.” Bedrock is comprised of silts and bits that swirl mostly beneath the commerce of jet streams and waves. Nearly all of it, however, less it move to a littoral cell or hadal canyon, will make landfall. As “Sea Choirs” specifies, “we shall never be done / with the granularity of time we shall never be done.” Returning to this prosaically strand-bound poem, meaning is the granular remainder of a formalistic (tidal, not stricto sensu cyclical or synthetically-duplicative) repetition. There is no Sorites paradox regarding when meanings become meaningful, nor any subjectivist spinning about. In “I Maye,” one reads a spoof of the Lazarian attempt to principle the cosmos. Heidegger’s precarious Dasein, for instance, forbids any death-initiate’s return as a matter of mortal course. This would be, as Prufrock recounts, to “roll it toward some overwhelming question.” What “I Maye” does is justly insist that even material repetition and its meaningful remainders cannot manifest but through a specific topos, a heteronymous theme or indexical matrix of already rooted ideas:

As the child of a century engrossed by totalities, I quickly understood that there was something that would always escape all our additions, and that it was this remainder, this leftover sum, unincluded by the Somme, that I had to refrain for my own operations… I consider myself a man who retells rivers.

The Somme is alive to transcription, retelling, the calling back to a place or state: the re-vocation of wave-writing, of ἀπόφανσις. This “unincluded by the Somme” is of course a cheeky reference to where Russell’s Paradox could not tread, the languagy non-Fregean topographies of space and its precarious “North.” The Somme is a superset of possibilities. In refraining “this remainder,” Lazarus, reawakening from Modernism, keeps what is prosaically repeatable in check, in reserve, under observation.

Yes, the steady-state austerity and returnability of “North” is somehow superabundant, not in found objects, but in ecologic leftovers and the chthonic rejections of empire. It is host to its own entombments and variable preservations. Like the pagan C-note bassooning through the beginning of Stravinsky’s 1913 The Rite of Spring—what Eliot certified as the “barbaric cries of modern life” rendered musical—Darras’ northerly wanderer happens upon discretional tones and artifacts. They will always emerge au passant, on a “Voyage,” “As in the mummy of that reindeer hunter, frozen in the crevasse of a glacier for over fifteen thousand years. / Future venison for archeologists out hunting.” Glacial time has outstripped even the structuralist taboo of cannibalism. Unlike Stevens’ anthropizing and perhaps civilizing hilltop jar, that “made the slovenly wilderness / Surround that hill,” the occurrence of the frozen reindeer hunter flattens a want for archai and archeological findings into a naïve hunger. Funnily the problematic of primitivism and l’art naïf is here a matter of science-think, not of painting, writing, poetry.

What’s more, a meal of knowledge is Darras’ Nietzschean rebuff to Cartesian dicta. Obviously matters of taste and digestion will not map very precisely onto a dogmatic mind-body problematic. Eliot’s “Prufrock” again offers its semperverdent and mundane complement, whereupon dubious time can “drop a question on your plate.” This “North,” being “A philosophy more ursulian than cartesian,” is a hibernating place probably more recognizable as Gallo-Rome than papist France. The featured personage of Descartes, however, splayed across poems, constitutes a dialogue charged as much with chumminess as with estrangement or bad blood. Darras’ callings to Descartes (“René come down from your Frisia”) evince a wanderer who was never necessarily a north-ist or north-ite by jus soli or jus sanguinis. He understands that a name, Descartes, even Darras, can be born one place and be borne another. Transcriptive poems, like the terra itself, take up definitions, take up their very shapes, according to unseen borderlands, and perilously-subtle or unnoticed relationships. Here the quite-northerly quite-Protestant “Cogito ergo sum” was always already the reductive and imperious basis for every southern vulgarity. It was an annotation of the existentialism of emperors, those who simply decided, “Sum.” This being so, Rome’s citifying horror vaccui, its gridded Vitruvian mandate merely to look firm, is all so much the same melting wax of empire, with its scientifistic credos and insecure deathgrip on space, its semifreddo deathgrip. The imprisoned northerner in the Capitoline Museum wriggles here again in glorious and therefore suspect defiance.

These historico-critical acts of Darras’ transcriptions somewhat diminish any maudlin fevers otherwise presumed to be lurking about in would-be nature poetry. Elsewhere the precarious interwar tones quaver unabated at water’s edge; a miasma still hangs over Thebes. Any avid quest for natural knowing or common truths, here, smelling the salt of La Manche, seem often to constitute an English romaunt, not a Greek tragedy. During our “Voyage,” the question is posed abruptly: “But can war be forgotten when the Brit helicopters are so intent on rotoring their honey from the pale blue leaf of the sky, ready to spit their flames of Hell onto the entry to Purgatory?” The wanderer feels the winds as they blow from Normandy, over the Crique de Rouen (what reads cognatically like a Kant text until it becomes the flowing “Seine”), over the Somme, to Calais, to Dunkirk. Those aforementioned worries over an Icarian drowning yield to concern over its political avatar: self-centeredness. War, la Terreur, is a getting-swept-away in one’s own fancies. It is delivered on the wings of the bonnes pensées that are themselves nothing more than honeyed banalities. Unthinking triteness and high lyric are too often geminal. The hazard of the lyric is the hazard of the sanguine reactionary who gallops through language with his starry conspiracies, his connexions both facile and arbitrarily baroque. Even the notes of Calliope’s lyre tie up the air with a sweet violence. Dante appealed in his Purgatorio, “And here Calliope, strike a higher key, / Accompanying my song with that sweet air / which made the wretched Magpies feel a blow / that turned all hope of pardon to despair.”

Catullus floated this relation between lyricality and precarity when he remarked that the passionate one “must write what she says to her lover on wind and swift water.” Concordantly, in his 1990 Reith Lecture, “Should We Go On Growing Roses in Picardy? The future for our cultural heritages in Europe,” Darras asks, “Are we naïve enough to think of art in purely romantic terms of inspiration in isolation?” The tragic mania of romanticism (“the pale blue leaf of the sky” is a cliché of the romantic urge), always a risk for the exoticizing English, reminds of the occultic gobbledygook of Europe and its Hitlers. Strangely though, Darras’ poem makes to tighten the marital (a word one metathesis away from martial) bonds with England, as would all of Darras’ translations (traductions) of notable English works. One might adduce hereupon that the Vichy government was as much a fault of Wordsworthian daffodil-gazing as it was of Jenaism. Perhaps it is no surprise that the poet who wrote of subjectivist “inscapes” was a Tory. Yet it might indeed be surprising for many that, supposedly mountains and valleys away from Gerard Manley Hopkins, those of today’s poets dwelling on glib astrology seem possessed by the same religiose etiologic tendency. Wiseass Sylvia Plath of “Blackberrying” ribs, “The honey-feast of the berries has stunned them; they believe in heaven.”

•

There is, here and there, too much light, too much Apolline luminescence and Enlightened dancing in Darras. At its worst, it tips over, flooding in easy Gnosticism: “we philosophers / who make our way by foot, following / the path of photodosia.” It’s like Yeats or Wagner poeting or crescendoing about pagan sacrifice and splendorous redemption. Nietzsche probably would have complained that Darras often backs his poems into the harborage of an autotelic “soul,” a word that is frequently used across Darras’ oeuvre to buttress quandaries about the lyric and Europe as a flawed collective. It probably can’t be helped—whatever minute store of sentimental humanism may be crackling mistily at the horizon’s lower eyelid. The rhapsode of “I Maye” marks, “I consider myself a man who retells rivers. Not some fishmonger who retails bloody filets. But someone who speaks, someone who debits and credits his accounts of rivers at their very mouths. Whose speech might lead to the ultimate sea.” What is this “ultimate sea” upon which the excerpt terminates? Someplace farther off than the lyric, remote to any return upon a shore, some ἄσπετος (unsayable) ether? Perhaps the line is fittingly incontinent. It often seems the burden of any Francophone or Anglophone poetic can be reduced to a need to shrug off Eliot’s tensile Four Quartets. It is that ridiculous diapason radiating from the meadows and glens of poetry. Stevens was routinely prey to this modernly-domesticated crop of narcissi, to what Ted Hughes discerned to be “a cauldron of daffodils, boiling gently.” It is the unmistakable pastis in every poetic libation, however sweet, the stern lightning rod sticking through every furor poeticus, however inconsequential.

Gladly Sieburth’s American-Englishings of the French, taken together, convey the temperament of a permanent if swollen-footed surveyor, not an emanationist or messianic lyricist. Leave weary time at the door, future, past or present; it is these damned coastal grammars with which a peripatetic must always eventually contend. In traveling, in being on a “Voyage,” one finds that English grammar is finally a land ripe for shared assimilations:

The grammar of the neuter is a blessing.

To say il y a in French is to be indifferently neuter.

The unsinkable languages that will manage to navigate their way through the spaces of the future will feature neuters that are structured, neuters ripe for conjugation.

English always says “it” when a stone or crease of wave assumes an eminence, an immanence.

Even if one would rather chalk up to aphoristic bravado Stevens’ edict in “Adagia” that “French and English constitute a single language,” an Anglo-American affinity in Darras’ work is difficult to shirk. Glancing at his publications, one will read more American and English names than French. Such a correspondence has been mutually conducted for as long as there have been poets to lay claim to American poetical conventions, to an American poetry. This may be particularly apparent in the 1980s, with its cross-lingual flurry of translation and anthologizing. As prolific translator Mary Ann Caws later wrote in her introduction to The Yale Anthology of Twentieth Century French Poetry, “The impact of French prose poetry on contemporary American poets cannot be overstated and is overtly present in the works of John Ashbery, Michael Palmer and Gustaf Sobin.”

•

It should by now be evident that Darras’ poetry is not from the scenic anywhere so familiar to the I-me poetry of today’s younger poets who took up where John Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror left off. Alice Notley’s poem, “The Anthology,” announces the constraints for such I-me poetry in a single Grace Paley-like outburst: “Mentally we are the cast of one epic thought: You.” One can read in Ashbery’s lilting and recursive poetic the wave patterns of prose. The dithering convexities of a tyrannical subject can give way to a capillary rustle of sediments that is, at its most potent, nothing less than the slow sarcastic redistribution of instincts, of natures. This is perhaps never more the case than in his long poem, “A Wave,” where “each of us has to remain alone, conscious of / each other / Until the day when war absolves us of our differences,” the day when island languages meet out upon the undifferentiated slush of high lyric and insane seas. As “Voyage” takes up, “Common space common sea / As in ‘commons.’” What has been billed as Ashbery’s skepticism about shared places by Perloff and others, however, is often just the rosy-cheeked passage around a hermeneutic circle, where constant I-me-themed cycling conjures sudden and almost abreactive insight. Sobin, a poet who studied with Heidegger, can read more like Darras, bearing witness to the topographic eminences of languagy phenomena in such poems as “A Self-Portrait in Late Autumn,” with its “verb-studded landscapes.” Words are themselves—as one might derive from the philosopher of being-there-in-a-certain-moody-way-toward-death—already beings in the world.

Darras’ own “Voyage” reminds that “North… / does nothing to forbid the body in all its vulnerable and trembling flesh from inhabiting the rawness of death.” But this prospective terminus is quivering with a futurity inferred by an endless record of historical reanimation. For instance, the daffy “Reveries” apes the poetry of knight, Philippe de Rémi. Renewed by Darras’ wanderings, this Middle Ages northerner is like another frozen mummy for poets “out hunting.” Such material is vast in its thematic recurrence. Just read Bernadette Mayer’s “After Catullus and Horace” or Barbara Guest’s “Dido to Aeneas.” Even he whose name was writ out on the water, Keats, oscillates in diverse magnitudes across the poetries that succeeded him. What is as inevitable as being-toward-death, as the I-me dying, is, brutally put, a reliving through someone else’s experiences. The harrowing outer space of death has always been thus settled, colonized and raided—to modify and appropriate an idea of poetic inheritance offered by Seamus Heaney, also a poet of northerly places. The poems in Darras’ collection help territorialize the conclusion of death, strip it from the tortuous dialecticism of subject-object talk—what is ultimately a more philosophic version of what Heidegger called Gerede, idle chat that, in being passed along, predicates every discourse before it has even pushed off.

Guarding against this across Darras and these transcriptions is an almost pre-Socratic earthliness. It can verge on elementalism, an obeisance to some genius loci, the sort Heaney quarrels with in his 1995 Nobel Lecture, where he says, “Once again, I hope I am not being sentimental or simply fetishizing—as we have learnt to say—the local.” Darras himself is not necessarily interested in succession, in a nation-stated Picardy, in being the Leopardi of “North.” As Darras himself delivered during his Reith Lecture, speaking about European orbits, “We should avoid being dragged back into the pits and traps of national identities, that is[,] of symbolic adhesion to a piece of cloth or a flag…” Poetry, accomplished poetry, is precarious, any which way one treads. Murmuring at its limits, it is an expanse with which “we shall never be done.”