Become Through Unbecoming: On Jackie Wang’s "The Sunflower Cast a Spell to Save Us from the Void"

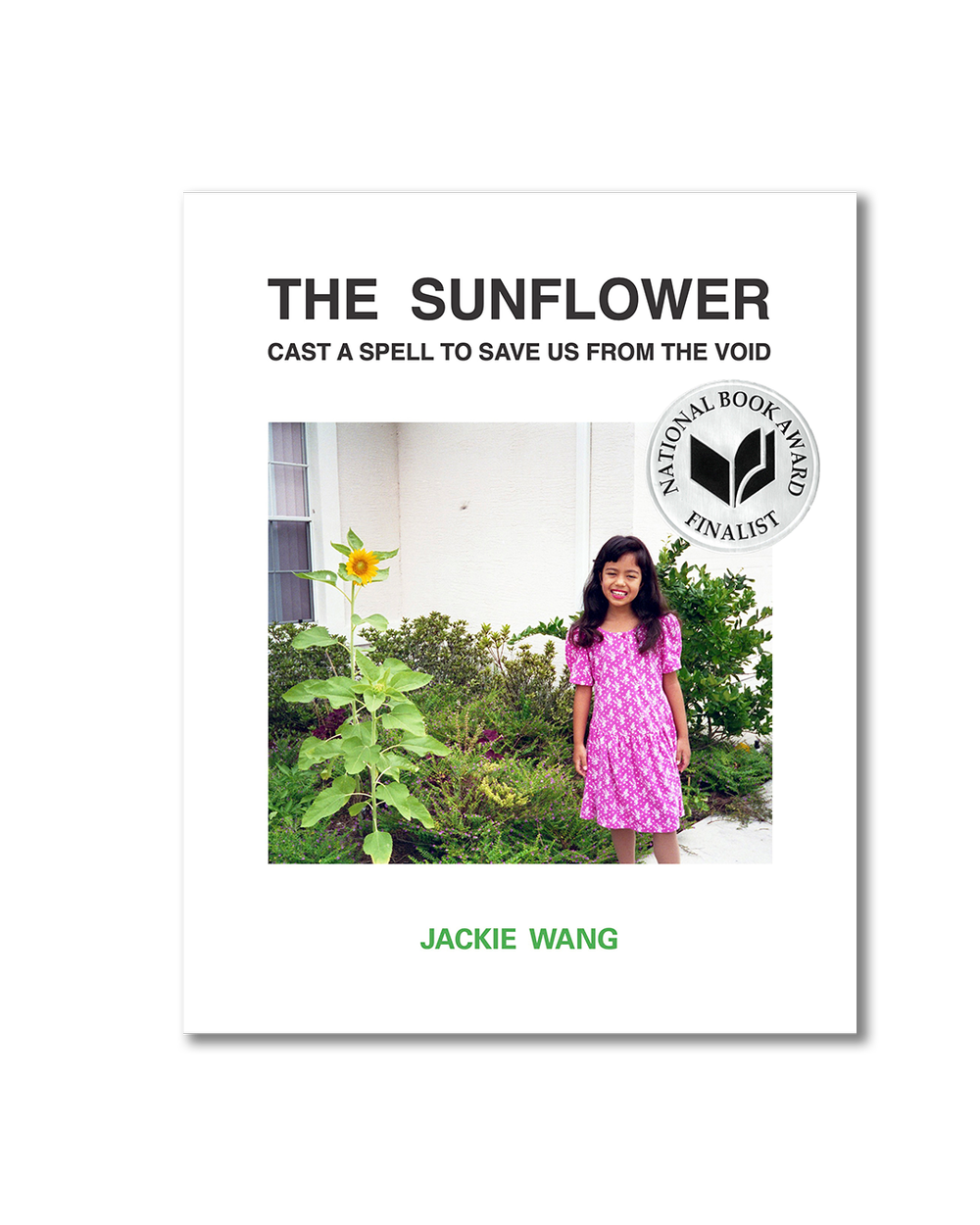

Jackie Wang | The Sunflower Cast a Spell to Save Us from the Void | Nightboat Books | 2021 | 120 Pages

Jackie Wang opens her debut book of poetry, The Sunflower Cast a Spell to Save Us from the Void, with:

TARKOVSKY’S CHIGNONS

TARKOVSKY’S CHIGNONS

TARKOVSKY’S CHIGNONS

(I dreamed I turned them in as my poems)

This collection, a 2021 National Book Award finalist for poetry, spirals in and out of the imaginary, like Andrei Tarkovky’s chignons on the backs of faceless heads. Still frames from Tarkovsky’s films The Sacrifice and The Mirror appear beneath Wang’s column of repetitive words, as though portals into her dreams. In Wang’s dreams, apocalypse eats its way into a beautifully encapsulated finality. Everything burns down, transforming us into willow trees. We find our way back home by train, back into a sequence of events, movements no longer freeze-frames, unlike the ones we are greeted with. Dreams, like fractals in a kaleidoscope, move into themselves, outpouring gracious melodies, reminiscent of our past selves, future selves, anxieties, ruptures, changes in the imaginary. Dreams, in Wang’s tonality, are ever morphing. Dreams are a social space. Dreams are a site of liminality, an in-between, convergent in crisis with “what has been disavowed in the waking life,” said Wang in a post-reading discussion with Brandon Shimoda, hosted by Skylight Books on March 11, 2021. In each scene of crisis a scene of possibility co-originates. Wang’s dreams bequeath us with a glint of possibility amidst the tectonics of a new but anticipated wreckage.

This book’s generosity is vast, deep, torrential. “I give them my words,” writes Wang; line oneirogenic in its largesse. What gifts these words become as Wang navigates her subconscious in tandem with the mycelium network of the collective. “Mystification is not a part of my act. I want to be naked and to penetrate my audience with denuded truth,” she continues. And she does, imbuing the reader with a certain naked phantasmagoria in their act of reading. Of dreams in lyrical passages undefined by form or genre, sculpted unpredictably, spiraling on like the coiled chignons that greeted us. The poet’s subconscious isn’t censored in this movement from disaster to prophecy. The narrator is self-aware, writing in the language of an effusive, nonlinear temporality born of a nebula.

Recurring images of shame, performance, and the emergent climate apocalypse–when visible in the vastness of these opaque dream networks—conduct the book as an explosive creation story. Wang brings us a platter bearing the explosion’s wound, which is hers: “My wound becomes the law / My wound is too grave to be scrutinized, too heavy to speak,” the text intones. As trauma inflicts injury upon others in a seizure of power, inhaling all life, Wang renders a recalcitrant counter-ethos in the face of carceral states, assisting us in our somnambulic journey to resist assimilation, to become through unbecoming, a scattered constellation. We, as readers, are directed into dreams of catastrophe: land integrated into surveillance, the optics of the internet, the nexus space. In these dreams, at times solidified in nightmares, we haven’t yet become, straddling assimilation and dissolution. Wang’s wound is a collective injury and is inclusive of her reader, structured in the eye of the impending storm, the lens of the security camera.

Wang’s denouncement of an embodied surveillance state buries itself in a form of “becoming” that is contingent upon mirroring oneself in the other. This becomes a means of escape from totalitarianism. In lieu of continuing to hide under repressive conditions, though the layers of shame remain, Wang abdicates to visibility. “By making myself visible I remove the anxiety of being found.” We are included in this motion of translucence—in allowing herself to be in the open, she no longer deceives, demonstrating our own strangely concocted deceptions. This acknowledgment of complicity evokes a survival contingent upon being alive, in sight, in motion with other bodies. We are turned into accomplices by reading, as a mask of ceremonious enactments used to blend in, to deceive, is removed. In turn we are given a neon balaclava, extreme and vivid; in solidarity with a sunflower’s radiance, we fuck, we should, we finally stop hiding. Wang asks us, holding the book, scanning its pages, to not be, via the scheme of collective dreaming. The antidote to being found, to being seen in a massive apparatus controlling interiority from the exterior, is to unbecome, letting go of fixed identity.

Becoming would indeed require us to recede into the landscape of chaos; resistance is reliant on unbecoming. “The Law requires we exist / I become, painfully, by condemning you,” she writes. Becoming would require internalizing the punitive state. In Wang’s dreams, in encompassing the collective, feelings have been consumed and consummated by product, the reproducible; revealing that a neon balaclava is one of the few available antidotes to shame, to “public scrutiny” of our friends who, with the winds, have turned on us. “Instead of thickening my skin I buy a new Balaclava.” Wang is aware of capitalism’s propensity to devour; even in a dream, portions of resistance can still be purchased, the Market isn’t too far off. Is it within us, or is it us within it? The ideas are interchangeable. There is no chicken or egg, only a constant reversal of roles in the dream space. Wang demonstrates to us the catastrophe materialized by human hubris as a slow burning flame engorged with us all, quoting Etel Adan: “We are all contemplatives of an ongoing apocalypse.” Wang’s poesy allows for the text to move through us (through our own wounds), guiding us away from disaster.

Even within bouts of melancholia or fear, the lyrics of Wang’s dreams are irresistibly prone to euphoria, bringing us to a spire of existence in decay, to a resistance against a mechanical, immutable space in the context of contemporary loss, a literal loss of a space to inhabit. Yet this loss isn’t a new phenomena; it’s only new for the Market. Yes, we continue to be implicated. As though what’s manufactured, in abandonment, reflects its innards; industrial burn, a quiet omnipresent force, turns glaringly obvious out of its context. “And why, when industry leaves city does it look like a bomb has gone off?” The question at hand is answered in its present form; the bomb is the industry; the origin is explosive.

Abandonment of the destroyed city clears any previous subterfuge, allowing Wang and ourselves to come to terms with finitude, to find glimmer in the previously manufactured void. The dream is not manufactured, it is collective. “Ah, but there are young people, willing to inhabit the ruin. To channel their immense energy into terraforming the wreck.” Wang begins to build on ruins, with a certitude of abandoned words, channeling her immense energy into the post-colonial state no longer extant in any authenticity—we are left with remains to be built atop. Ruin does not denote death, does not denote a lack of material. Does not denote an emptiness. Something persists, assisting new growth, an imaginative force. “Terraforming the wreck,” channeling sunshine, the sunflower’s spell into the earth, Wang’s sunflower is an antenna calling for grounding, spitting its current beneath the soil. “Capitalism isn’t a bed of sunflowers.”

We are being probed with an idea of true form within wreckage. A delicate shell at the beach breaks as Wang attempts to clean off the goo to uncover it. “I look down and see a hole in her side. Feel so sick. I don’t understand what has changed, but I know I will never be able to touch you again.” Here, the “you” transforms the reader into a desirous form, yearning for something pure in an attempt at a primordial wholeness shaped by an untempered state. We won’t be touched. There is too much space between the words typed upon the pages and our eyes. Only constellations emerge. Contending with this sentiment, in Wang’s prose, hope lies in ordinary gestures, in the ability to exist within a duality:

I remember how devotional I felt that morning

the cottonwoods released their seeds to the wind

The way the morning mysteries formed the backdrop to my sadness.

This book asks us to emerge into a wholeness, a polarity of purity and corruption. A sadness within a devotion. A revelation emerges: “I woke up thinking that the British empire can never own the dreams, only its ‘residue’ — the artifact; the material on which the prophecy is inscribed, not the prophecy itself.” Together with the poet, we are awakened to the realization that the physical, the obtainable, is not analogous to the dream, nor the dreamer. The threshold is ephemeral, contained in the wildness of shapeshifting. Matter in a diaphanous condition. Wang’s matter is “an irrigation ditch, [where] two dried bodies are still holding hands.” We are constantly being asked to redefine being through an immeasurable faith in love amid displacement and destruction. What does it mean to unbecome? There is something of disembodiment. Wang begins to depict a sort of transience, a landlessness, interrogating any and all previous assumptions; borders are constructed, as is time, and a dream is a boundless eternity:

A symphony of rats becomes the echo of a text written by the one

who does not belong anywhere

The “voice of exile,” Du Bois said of the sorrow songs

Of people outside time, without ground.

Knowledge of impermanence, under no duress of ownership, relays itself into Wang’s immateriality of dreams turned diurnal mediation. “I thought of Anne Carson’s translations of Sappho where brackets appear in the poems where the papyrus has disintegrated as papyrus is the structure of dreams.” Fleeting structures represent the abandoned city made of concrete and metal, “never intact, half dissolved” bodies connecting the impossible, morphing the collusion and disintegration. It is also Anne Carson who writes, “Nothing vast enters the lives of mortals without ruin.” We, the readers, splinter into shards at these words, as we continue the enactment of ruin, of our previous notions of genre, poetry, form. Our physicality, our dreams, deprived of containment, begin to explore the pages with Wang. A collaboration ensues, if only for a second; a small, magical impermanence scrapes itself into our form, our minds. Fragments survive; liminality, the in-between space gives way to growth beneath decay. What is left after the “end,” after “dissolvent?” New matter. Possibility.

The sun is an orb of energy, the nurturer of life. In the book’s pictographic illustrations, the sun is a black hole. Drawn by Kalan Sherrard, the illustrations accompanying Wang’s dreams depict a clump of angels, a cave surrounded by neoliberalism, elucidative of possibility within the void. “Here is the destroyed world, and here—beyond the threshold—is the luminous world,” “creating openings,” where there are holes, gaps, chasms. “Experience completes me,” she writes, implicating the reader into the allegory of existence. Existence, after all, in Wang’s world, is a disintegration into the collective space, the face of the sunflower, a black hole of infinite possibility.

The infinite, we are reminded, in Glissantian terms, lives in the opaque. Eduard Glissant asks for the “right to opacity,” for individuals, for those who we do not understand, for whom we deem “Other.” Opacity resigns knowledge and informative understanding to possibility, a trace of a connective thread. The question emerges: “How can I know you if I don’t understand you?” Glissant calls for relation, a distant past of connectivity, traces left in the void. In Wang’s search for herself, a certitude of the invite is in the void, in the depressions of destructions, too, calling for opacity, a love through a trace. In Wang’s dreams, sculptured into a psychical archive in the book we hold in our hands, we unbecome by being, by dissolving into the face of the sunflower: an opening for love.