The Problem with Advice: On “Sex and the Single Woman”

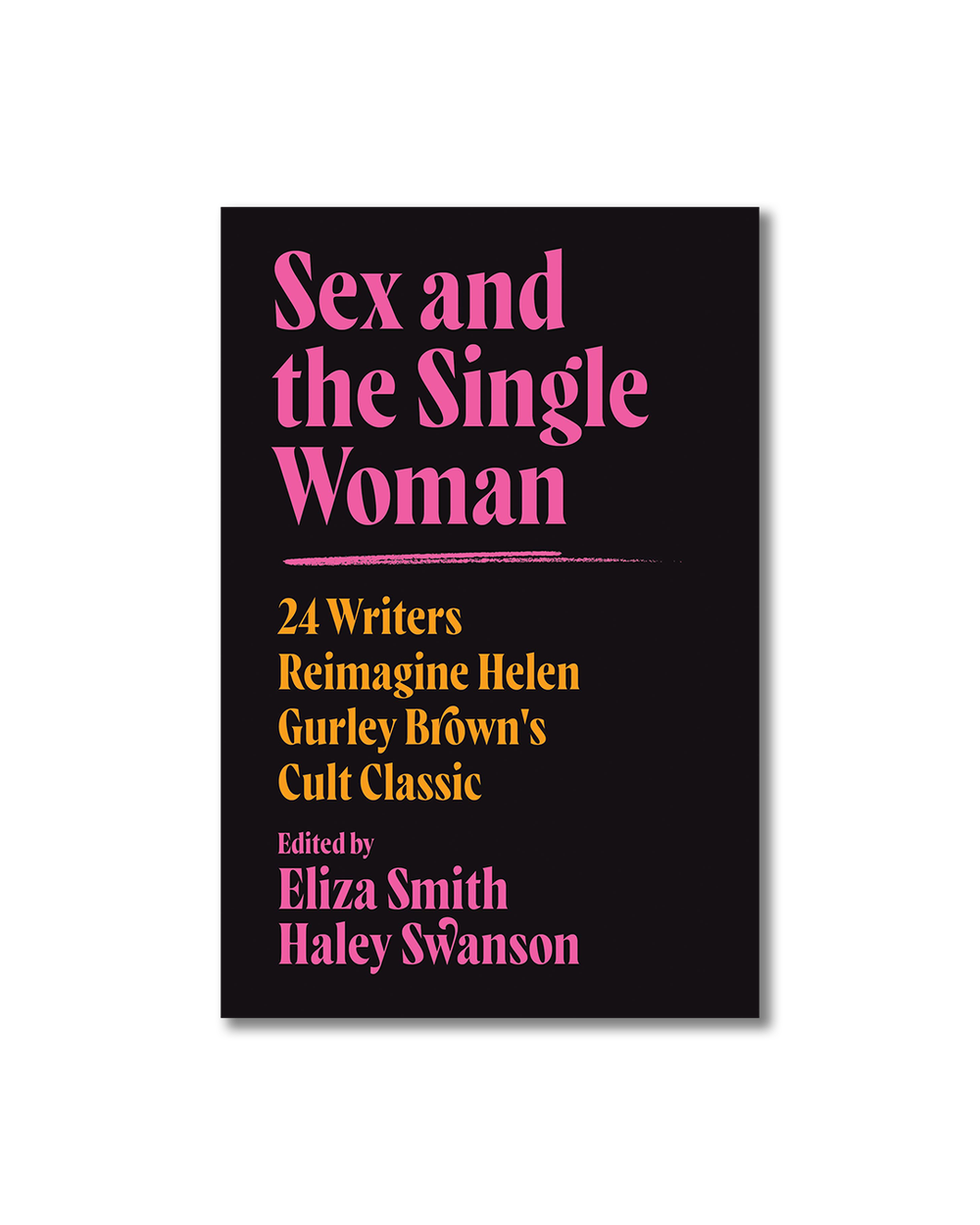

Eliza Smith and Haley Swanson, eds. | Sex and the Single Woman: 24 Writers Reimagine Helen Gurley Brown's Cult Classic | Harper Perennial | 2022 | 272 Pages

Can dating advice ever be universal? How can an idea as general as “advice” on romantic life, or singlehood, apply to any specific instance of one body negotiating with one or several other bodies? How can writers address this problem? These questions were top of mind when I began reading Sex and the Single Woman: 24 Writers Reimagine Helen Gurley Brown's Cult Classic. This anthology, edited by Eliza Smith and Haley Swanson, was compiled to honor, update, critique, and revise Brown’s classic advice book, Sex and the Single Girl: the Unmarried Girl’s Guide to Men, sixty years after its initial release.

Helen Gurley Brown was a writer, editor-in-chief at Cosmopolitan from 1965 to 1997, and primordial girlboss. In the 1960s, her book equipped single women with a plan of action for how to date, how to manage finances, and “how to be sexy.” She offered ideas that were progressive and exciting within the context of its time: that women could live fulfilling, sexual, financially-independent lives, all while being single. Unfortunately, in Brown’s construction, the purpose of a fulfilling single life was to make yourself more appealing to men and thus stop being single all together. Brown uses cutesy nonsense words like “pippy-poo” and in interviews speaks in a seductive drawl she taught herself by studying celebrities. She recommends that single girls do the same. Sex and the Single Girl is the origin of the infamous “egg and wine diet,” which was later reprinted in Vogue, and will circulate the internet every few years to remind everyone how unhinged the ‘70s were. Brown explained that she called women “girls” because to her, “girl” referred to a lifelong youthful quality: the “girl still in there whooshing around—loving fun, being spontaneous, mainlining on enthusiasm.”

Implicitly, the girls Brown addressed were also women like her or like the women she knew: white, straight, cis, able-bodied, thin by every means possible, and seeking a wealthy husband: women whose only separation from absolute privilege was that they were not married and not men. Throughout the new anthology, a wide array of writers work to reconcile the campy delights of Brown’s prose, the nostalgic solace some once found in her work with the misinformation she spread about HIV, the excuses she afforded for sexual harrassment, and the ways in which she upheld and contributed to oppressive norms. In her day, Brown encouraged readers to manipulate an unfair world to their advantage rather than work to change it—or as Samantha Allen puts it in the anthology, she was “urging women to play the game harder instead of flipping over the table.”

Sex and the Single Woman revises its advice-giving predecessor by challenging the idea of giving advice at all. In one of my favorite essays of the book, Self-Help, Morgan Parker writes, “I’ve never read a self-help book before. I don’t like when people tell me what to do, and I really hate when they’re telling everyone else the same thing.” This addresses one of the core issues of Brown’s book—that any piece of advice works well universally or without context; that being single or a girl are experiences with any sense of uniformity. Brown’s advice becomes at best irrelevant and at worst destructive when it’s offered to someone with a drastically different life experience than hers. Her conception of the world was limited by her place within it—like everyone’s is. The new anthology makes considerable effort to counteract this narrowness. The editors work to depict singlehood not as a unified state, but as something constellated among its citizens. By presenting the update as a collection, Swanson and Smith resist the authority of a singular voice—the frame that makes Brown’s prose as beguiling as it is disconcerting. The essays carefully avoid prescriptive suggestions and instead offer something more human: here’s who I am, here’s what happened to me, here’s how I came to peace with it or else how I didn’t.

Although these pieces explore singlehood through a range of perspectives, many of the narratives follow fairly similar trajectories. Several essays end with some iteration of the idea that the most important relationship in the speaker’s life is the one they have with themselves. Instead of a girl-meets-boy romance, one essay describes its structure as “Girl finds her way out of body-shaming and purity culture.” The essayists often achieve at least partial contentment when they unlearn patriarchal messages or practice healthy communication with their partners. These behaviors are wonderful, admirable goals, but at times I’m left wondering: what does that actually mean? Does taking yourself out to dinner really help that much? What if your therapist isn’t that good? What if you can’t find a moral? While there are moments of clarity—for example, when Josie Pickens tells us about the time her friend alerted her of her habit of emotional dumping, and we’re confronted with our own flaws—I often wanted the writing to press a little harder, to venture further into complication, and to demonstrate more vividly what living anti-patriarchally actually looks like. I wanted more scenes where healthy communication meant telling a partner something that would hurt them, or to hear more writers say something like: “actually, it can be very difficult to find the line between boundary and responsibility.” Some of the best essays are the ones in which the writer hasn’t quite found their way out, or in which women find singlehood livable but “still crave the comfort of a hand in mine, the warmth of being claimed in the daylight.” These essays confirm that the writer is being honest with their reader, and that they’re willing to depart from the narratives that are popular among—if not the world at large—at least the target demographic of this book.

Still, in a year during which bodily autonomy has come under direct attack, as anti-trans and anti-reproductive freedom legislation sweeps the country, maybe now isn’t the time to insist upon subtlety. Maybe my desire to see these writers struggle more with the particulars of these uncertainties speaks to my own precarity, or a hunger to see my own dilemmas play out in the lives of essayists—similar to how a woman might have read Sex and the Single Girl years ago and thought, “well that’s not how it is for me,” or like how Brown gazed out upon the single women of the country and believed they must be struggling in the same ways that she did. My resistance to some essays and affinity to others might prove Swanson and Smith’s point exactly: that different readers need to find different stories. That each single woman writes her own guide.