The Suppression of the Body: On Ella Baxter's "New Animal"

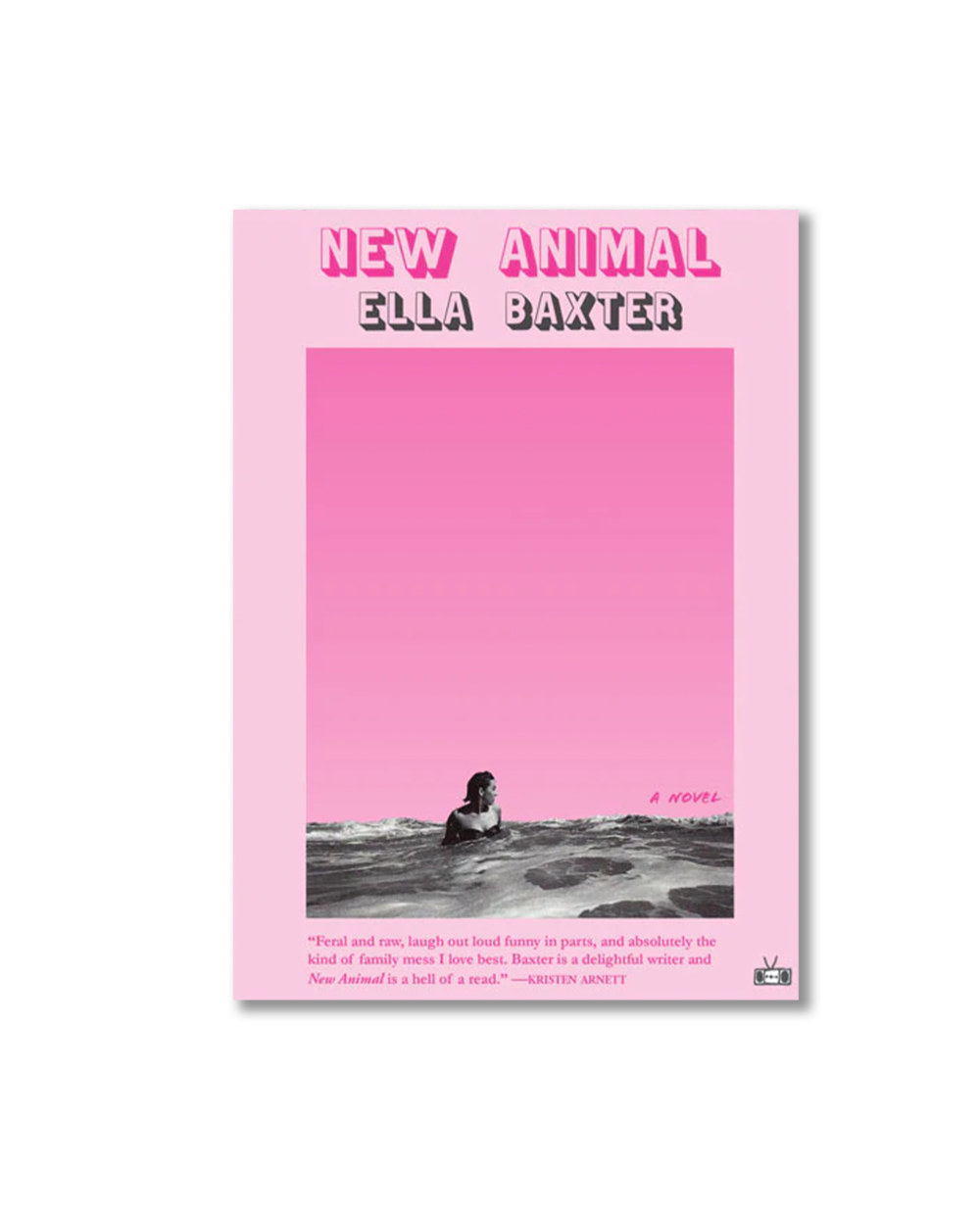

Ella Baxter | New Animal | Two Dollar Radio | 2022 | 212 Pages

Ella Baxter has emerged with New Animal, her debut novel about Amelia, a woman lost amid fraying personal relationships and newfound grief. Devastated by the sudden death of her mother, Amelia acts animalistically, in need of taming and caressing. She yearns to be coddled by other people’s bodies, a form of distraction from the compounding loss that starts consuming her life. She seeks solace in dating app hookups and eventually a BDSM club.

In her exploration of the process of Amelia’s grief, Baxter delves into the existential angst often portrayed in millennial novels. In one passage, Amelia thinks to herself, “Ever since, I go to the ravine and stand on the edge; it helps me to know that humans are too sensitive for a world as hectic and harsh as this.” Contemporaneous examples abound—Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends and Raven Leilani’s Luster particularly come to mind—of novels centered on young female characters trying to find their place in the world through their work and art. Baxter’s Amelia follows the same pattern, but with a twist: as in Ottessa Mosfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, this female protagonist is profoundly unlikable. Amelia narrates her life with a caustic tone, perhaps in response to the grim reality of her experiences.

Death is an everyday presence in Amelia’s world. She works as a cosmetic mortician in her family’s mortuary business, painting bodies to be seen by bereaved loved ones. Most outsiders perceive her job to be ghoulish, but she notes, “the deceased are beyond beautiful, but only because they are so emptied of worry. Everything tense or unlikable is gone.” Amelia has a close understanding of the process of how bodies decay, and her thinking about her work challenges Western norms that cover up the inevitability of death. She rationalizes each passing as part of nature and detaches from the circumstances that bring an end to each life.

Despite her intimacy with funerals, Amelia refuses to attend her own mother’s, instead stuffing herself full of the marzipan that her mother had made earlier in the week for mourners at the family funeral home. Animal instincts kick in, and Amelia finds she can distract herself from grief by putting her body in discomfort. That monologue about how all deceased bodies are beautiful dissipates when she fails to rationalize her mother’s death. Her search for escape through an alternative pain eventually leads her to go to a BDSM club with a stranger, hoping to be resurrected into someone new: “that’s what I need. I need to put this girl to rest.”

Other contemporary novelists have skirted the borders of the kink community by including characters who attempt to partake in BDSM. Most famously, Sally Rooney received criticism for portraying the community in a harmful manner through the characters Marianne and Jamie in Normal People. According to Rooney, Marianne subjects herself to the acts imposed on her by Jamie because of emotional and physical abuses in her past. Normal People perpetuated the idea that members of the kink community are drawn to acts of subjugation as a result of histories of abuse—a theme explored earlier by Mary Gaitskill in her short story collection Bad Behavior. Baxter stands apart from these authors for introducing the reader to BDSM and kink with a deeper understanding of agency and consent. She allows her main character to explore the world of domination and submission as a means of actively distracting herself from her mother’s funeral and her own grief. While Baxter pushes Amelia to the edge, she doesn’t fall into the trope of portraying those interested in kink as victims seeking resolution for past abuse.

Throughout the novel, the metaphor of Amelia’s body needing to be sedated and compressed by other bodies runs rampant. Amelia follows her basic instincts to copulate, believing that she becomes a new animal when she is with someone: “my body feels as if it’s made bigger and more powerful when I have another person inside me. You know, like I have two sets of lungs two hearts, two brains. I am a beast, and I can’t think because I’m in beast mode.” She becomes “medicated” and “anesthetized” by other bodies, working to survive her pain alone. Amelia lives in a state of shock about the unfolding of her life—the only balm for this pain that she can find is in the act of becoming an animal conjoined with others.

Baxter takes on a refreshingly real and acerbic tone in her portrayal of Amelia, exploring the inner psyche of a young woman attempting to piece together her existence in the modern world. As one of the other characters says to Amelia in regard to her mother, “no thinking woman is [happy]… life is either boring or shocking, there’s not much in between.” New Animal offers a new take on the aging millennial novel.