Surpassing the Moment: On Elisa Gonzalez’s “Grand Tour”

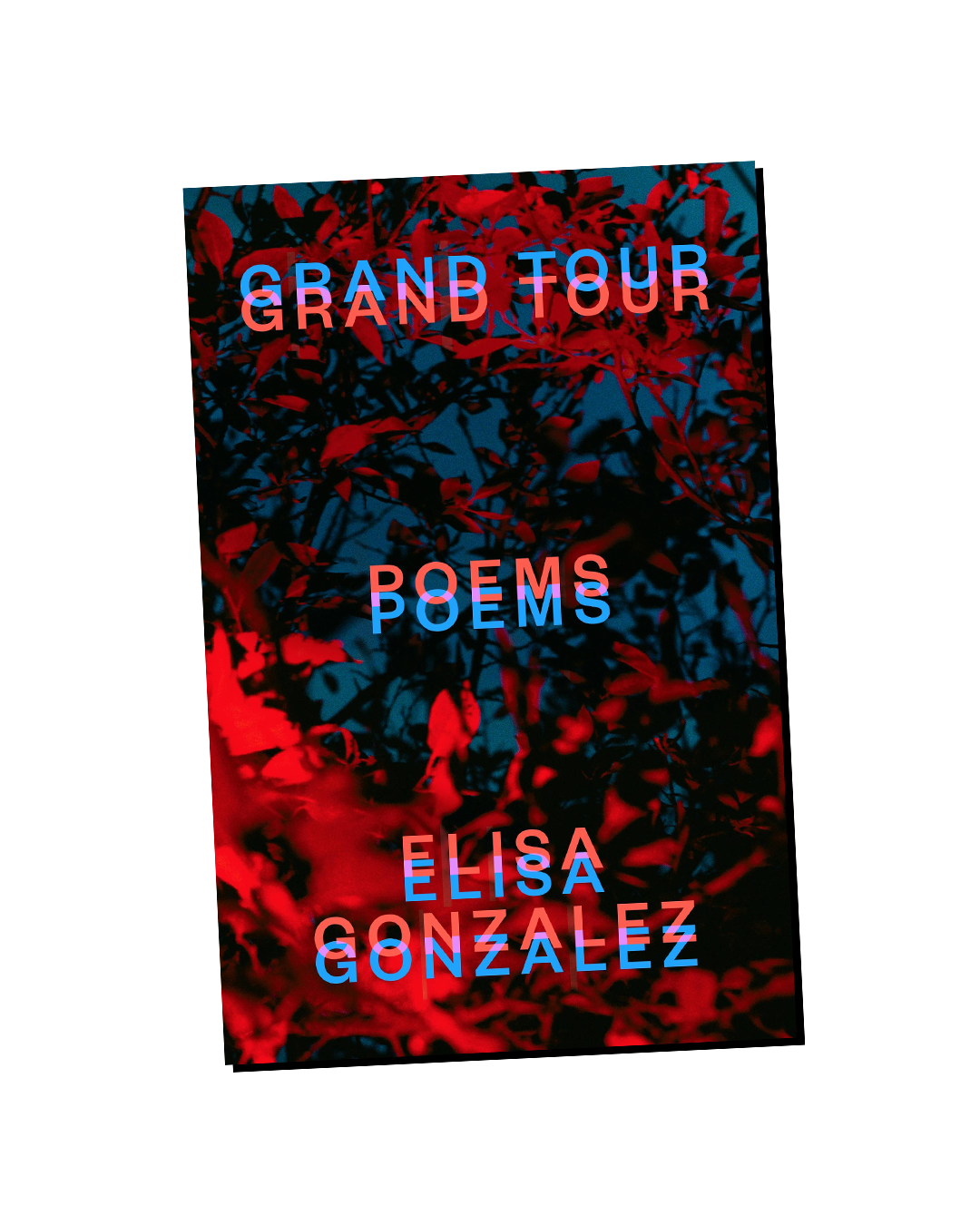

Elisa Gonzalez | Grand Tour | Farrar, Straus and Giroux | September 2023 | 112 Pages

“Whatever else it may be, a poem is a work of art made of words, and the way in which a particular poem’s language creates the repeatable event of itself is my preoccupation,” wrote the late poet and critic James Longenbach in his book The Lyric Now. While lyric poetry historically emerged as a genre meant to be sung or recited with musical accompaniment (such as the lyre, from which the genre takes its name), literary critics have long debated the nature of lyric poems. In his final critical work, Longenbach is less interested in such theoretical debates. Instead, he adopts the history to focus on poem-as-event—much as a poem would have been when performed with a lyre. For Longenbach, poetry is equipped with “strategies for staging its own immediacy, as if the poem were written in the time it takes to be read.” “Whether written in 1920 or 2020,” he asserts, “a poem creates the moment as we enter it. The poem is happening now.”

For Elisa Gonzalez’s debut poetry collection, Longenbach’s criticism reads as a guiding companion. The poems in Grand Tour are marked by restlessness: their speakers seem uncomfortable, even trapped, within their lyric moments, finding their circumstances lacking—overshadowed by their past and ready to be subsumed by their future—and consequently resist the all-too-oppressive presence of their lyric moments. They crave transformation. “What’s next?” the poems seem to ask, only to be provided the metaphorical silence and the physical white space of the page at each poem’s end.

As early as the first stanza of the first poem (“Notes Toward an Elegy”) are hints of this impulse toward transformation:

The Cypriot sun is impatient, a woman undressed

who can’t spare the time to dress, so light

like a vitrine holds even a storm.

One day in the Old City, a pineapple rain.

And I’m on my way home from the pharmacy, carrying

my little bag of cures.

Refuge at the café in the nameless square.

Nihal brings espresso poured over ice, turns off the music.

We listen to rain fall through the light until the end.

Here, a rapid succession of metaphors alters the otherwise bare, mundane scene: walking through Cyprus’s Old City on a rainy, yet sunny, day, carrying medicine from the pharmacy, the speaker stops to sit in a café, drink espresso, and wait for the rain to end. Why not simply write that? Instead, the sun is a woman, the rain during a sunny day is a “pineapple rain,” and transported medicine constitutes a “little bag of cures.” This pattern of obfuscation continues: a “lion rampant in the sky” is presumably the constellation Leo, and mountains are not mountains but “a fist knuckled on the horizon.”

These metaphors are not only instances of things not-quite-there (our speaker “accept[s] the presence of dances invisible to [her]”): they are brief, implied revisions of past events (our speaker, through this tactic, suggests she wills “the presence of dances invisible to [her]”). Though there is a hint the scene I’ve excerpted above occurred in the past (“one day”), the present-tense timing of the poem’s lyric utterance emerges most clearly in its final stanza. Through an accumulation of narratively disjointed stanzas and sentence fragments, we arrive at this resting place: “Examples of what, I do not know.” Yet in this “lyric now” of the poem, our resting place is precisely one which the speaker “does not know,” one of solitary musing. The final stanza recasts the entire poem as a drama of memory: the past is transformed into an idyllic revision, even as the true past becomes inaccessible and unwanted. This stanza juxtaposes the past when the speaker “took Love out walking / with me everywhere” with the present when she explains, “And now I lie awake pretending everyone in the world / lies still the way the living are still: / not entirely, never entirely.” In the poem’s present she admits to engaging in a revivification of a past made possible by the lyric moment of the poem. This poetic act allows the living and the dead to share in her restlessness, placing them on equal footing.

The lyric moment continues to assert pressure on the past in the more direct meditation “Failed Essay on Privilege.” Beginning with, and sustaining for four stanzas, the past tense—“I came from something popularly known as nothing / and in the coming I got a lot”—this poem allows the present tense to intrude with increasing intensity on the past as our speaker interjects with commentary:

Still, I was a guest there, I made myself at home.

And I know a fine shoe when I see one.

And I know to be sincerely sorry for those people’s problems.

I know to want nothing more

than it would be so nice to have

and I confess I’ll never hate what I’ve been given

as much as I wish I could.

Still, I thought I of all people understood Aristotle: what is and

isn’t the good life…

because, I wrote, privilege is an aggressive form of amnesia

By equating “privilege” with “amnesia,” the speaker suggests that her Yale education has given her a present moment bereft of an awareness of a less privileged past and the reality of those without her advantages. The interjections of the present tense are an act of erasure: the past tense “for a while I tried to condemn. / I wrote, Let me introduce you to evil” is replaced by the present tense “and I know to be sincerely sorry for those people’s problems”; “I left a house with no heat. I left the habit of hunger. I left a room / I shared with seven brothers and sisters I also left” is now “even the good is regrettable, or at least sometimes / should be regretted // yet to hate myself is not to absolve her.” The past yields to the present, and the poem repeatedly propels us forward from a past tense into its future, into what is our lyric now.

This strategy has surprising implications when we reach the last lines of the poem: “I paid so much / for wisdom, and look at all of this, look at all I have—” There’s a wry irony to these lines. “Look at all I have,” being at the end of the poem, directs the readers to literal absence, white space, by an em-dash; or perhaps we’re invited to imagine, off-page, a speaker surrounded by icons of her privilege. At any rate, the irony here, operating parallel to the poem’s pattern of discarding the past for the present, communicates a dissatisfaction with the lyric moment. The lines gesture toward an act that doesn’t get to happen (we never see “all she has”), toward a future that is outside of the confines of this poem, suggesting these words, too, will become another erased past. We’re left to wonder: Will the future lyric moment be satisfactory? The implied answer here is “of course not.” Just as the privileged vantage point of the present erases that of a past self unaware of what will come next, yet another moment will emerge, another erasing, more privileged present. Hence the “failure” of her “essay on privilege.”

The speakers (including that of “Failed Essay on Privilege”) of this collection are notable for their unique brand of voracity. They want more than their utterance, their “lyric now,” can necessarily provide; yet there’s tragedy to be found in the fact of the poems’ temporal inescapability—we’re stuck in a present of dramatized dissatisfaction. This is the tension inherent to these poems: on the one hand, a speaker’s wish to transcend the boundaries of the poem; on the other, the speaker’s implicit understanding that the poem is necessary (in a book of poetry!) to utter, dramatize, and enact that very wish for transcendence. We end up with a purposefully stunted vision of wish-fulfillment: no matter how much we wish for something different, at the poem’s end the speaker simply ceases to be, never having escaped her circumstances. The lyric now, then, provides the poems their driving force: it is a container to attempt to push out of, an enemy to defeat.

In this vision, to transcend and to utter become mutually exclusive circumstances: the lyric relegates its speaker to the moment of its utterance, and any transcendence necessarily requires casting aside that moment for an idealized next. The coexistence of these impulses brings us back to the work of James Longenbach, who preoccupied himself in much of his criticism with the dissolution of oppositional accounts of poetry. Writing of Kenneth Burke and Wallace Stevens in his 1994 book Wallace Stevens: The Plain Sense of Things, he states, “both writers knew that their words made something happen, but they were simultaneously aware of the difficulty and the danger of defining that process conclusively.” He acknowledges here the messy interrelationship of life and art; there is neither the consolation of a certain effect behind a lyric nor the absence of any effect whatsoever.

A similar ethos underlies Gonzalez’s writing, as evidenced by a comment she made in a 2023 interview with Jennifer Grotz in the Adroit Journal: “I worry about obscuring the impossibility of fully describing, about fixing something in narrative until I could no longer get it out of narrative. I worried most when putting together this book about the ‘solace’ that is often associated with traditional elegy.” The essential tension in her poetry—where the poem itself acts as a constraint on the speaker—complicates the speakers’ desires, preventing us from settling for an unsatisfying vision of mere wish-fulfillment (Imagine a poem communicating, “Watch this lyric offer solace, cure my dissatisfaction”). On the other hand, a poetics of absolute constraint might, in any case, lead to an equally unsatisfying poetry, with the speaker helplessly acquiescent to the mechanism of a given poem (“This moment of loss conveyed in the poem is an inescapable reality, offering only suffering”). There doesn’t get to be an easy, limiting resolution between the “life” of the speaker after the event of the poem and the “art” of the speaker in the lyric moment.

Habit, a term pondered in the poem “The Aorist,” seems exactly the right word to describe the rhetorical effect of repeating this strategy of attempting, though necessarily failing, to surpass the moment of the poem:

Your English says, When there was not

the two of us this hand

of mine still

reached for you.

Use this tense,

my textbook directs,

only when an action is

neither past nor present nor future.

I think, What freedom,

until I learn that only habit comes untied

from time.

What freedom, we imagine our speaker thinking, to be liberated from time itself, unlike the speakers in “Notes Toward an Elegy” or “Failed Essay on Privilege,” who use the present to alter the past, or to see the future and erase the present. The next line (“until I learn that only habit comes untied from time”), coupled with these rhetorical strategies, suggests our speakers’ repeated attempts to resist the lyric moment aren’t an inevitability but a disposition of the speaker. She is not able to be helped. It is a sort of compulsion, a desire to escape the present moment for the next. If habit includes the following—"To kiss, to go down, to come. / To stroke. To lift. To stray. To laugh. / To sleep, and of course to give.”—then, for Gonzalez’s speakers, it also includes “the urge to run”:

Your morning murmur: I’ll put the coffee on.

Why tell me, when you always do?

When messenger wind alarms the shutters.

When jasmine whirls through the gap.

When I rise. When I dress.

When I shut. When I goodbye.

As the speaker wonders why the addressee of this poem announces a habit of making coffee despite the speaker’s (implied) own habit of abandonment, we’re left to wonder an analogous question: Why does our speaker, too, feel the need to dramatize, in the utterance of these poems, her own habit of desiring to abandon the lyric moment, despite the impossibility of doing so? There is an implicit faith here, as with Stevens and Burke, that her words make something happen. Thinking this way, to speak them in the first place becomes an imperative.

That Gonzalez’s poetry rests uneasily between the poles of a freedom outside of the lyric moment and an inescapability of it inherent to poetry, that this dynamic changes nothing for the speakers they, or we, would most desire it to, that our speaker’s performed dissatisfaction in the elegiac mode doesn’t give her what she wants, doesn’t save her from herself or the “now” of the poem, is exactly what makes Grand Tour so rewardingly authentic.