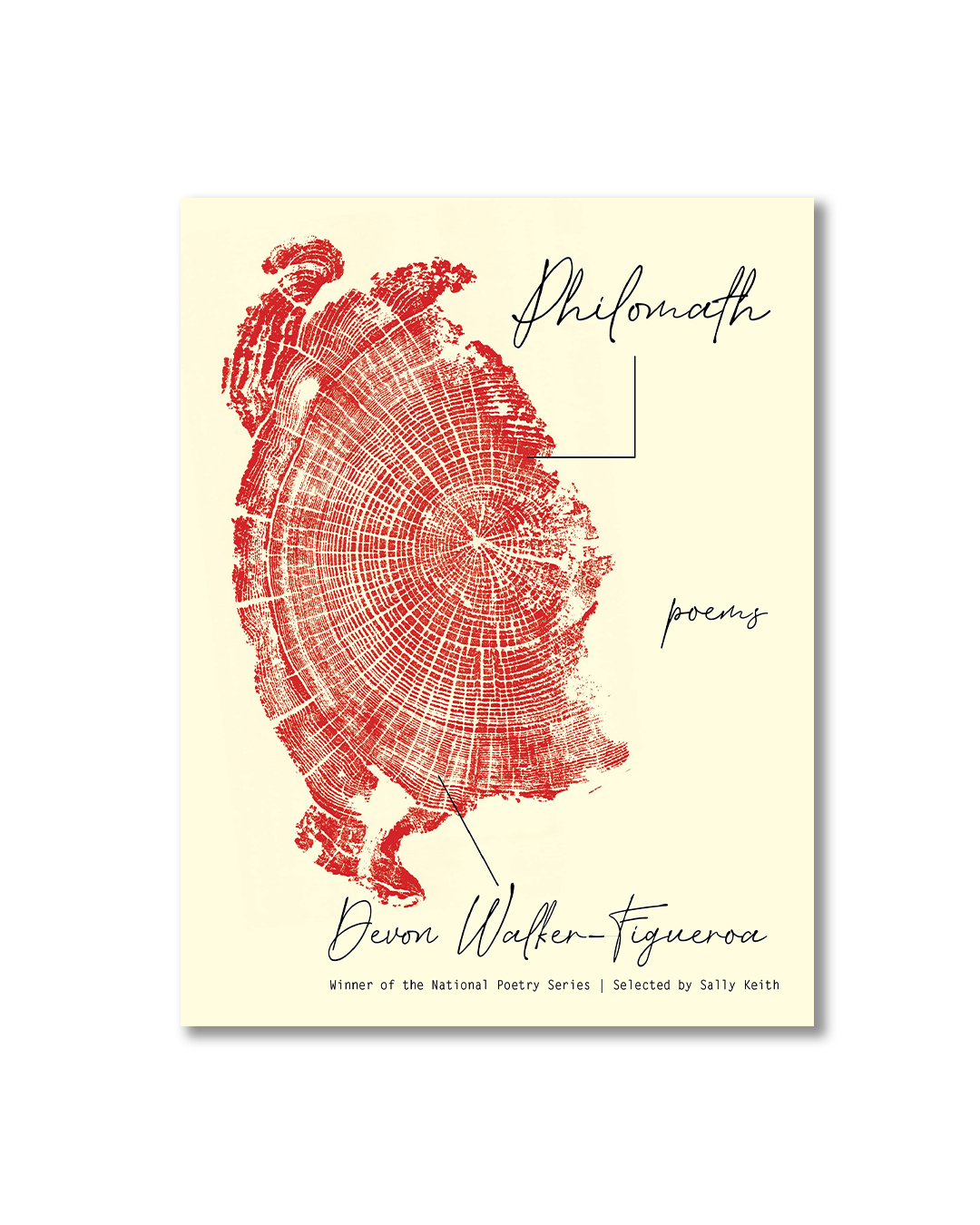

Seeing it Everywhere: On Devon Walker-Figueroa's "Philomath"

Devon Walker-Figueroa | Philomath | Milkweed Editions | 2021 | 96 Pages

“Sometimes it seems / the future has a habit of repeating itself” writes Devon Walker-Figueroa in her debut, Philomath, a poetry collection with two separate arms: a woman’s childhood and coming of age amongst the masculine fugue required to survive a ghost town, and the struggle for continuance amid capitalism’s exploitations and abandonments.

Walker-Figueroa’s place-based narrative encapsulates a life in the Pacific Northwest, specifically a literal ghost town in Kings Valley, Oregon. The town is marked by a feeling of scraping by, “a kind of sick that takes saving up for.” There are “gravel parking lots,” the “gutted sanctuaries of timber mills,” where the weird quirks and violence of organized religion are swallowed “because this is how you get close to God in Philomath.”

Philomath, the name of both abandoned town and the poetry collection, imbues the reader with a sense of discovery. Shane McCrae is right to say in his blurb that “[Walker-Figueroa] writes an America so absolutely American it has been forgotten by America, an America so American one can’t believe it exists unless one has lived there, and if one has lived there one recognizes it everywhere.” He is right to stipulate its recognition everywhere because we see it across this country—capitalism’s abandonments of exploited people.

By way of comparison, it is no coincidence that the people of Appalachia (where I grew up), who are historically bold enough to muster up armed insurgencies in dissent, have also been the subjects of a decades-long media smear campaign and left to fall into poverty and infrastructural decay. This has been well documented by collections such as William Brewer’s I Know Your Kind, to which Philomath bears a striking resemblance. Walker-Figueroa’s text joins this chorus of the exploited, demonstrating how our economic system maligns regions across the country, and that the Pacific Northwest has been decimated in many of the same ways as Appalachia and the Rust Belt—through economic austerity measures and entrapment in military, religion, and nationalism to serve an imperial endeavor:

…It seems we’ll get by

with our lie a little longer, if only

because the nematodes are failing

to save the Yukon Golds & the thistle is

going to seed & Mark, a family

friend who happens to be hard

up, is sleeping on the couch, asking us

to call him Lucky like it’s Desert

Storm all over again…

As with all good place-based writing, Philomath is more than pastoral; it is intensely personal and intimate with its surroundings. Walker-Figueroa demonstrates that a place is more than its ecosystem and infrastructure. More than anything else, it is its people. This is communicated through retellings of personal moments that color in their settings:

from a man who smokes a Marlboro Red

every hour of his life. I’m grateful for

the company, the mindless knock-

knock jokes, the scent of his leather jacker

in the closet. He has a way of being

the loneliest person you’ve ever met, besides

yourself, except when he’s holding

his Maverick & teaching you how

to aim for the hay man’s heart,

the one who wears the blue

button-up he forgot you

bought him for his birthday.

These recollections are all of intimate recognition–the poet refusing estrangement from her place of origin. The collection includes an abundance of longer poems, displaying a tendency towards generosity of description akin to that of Ross Gay rather than crystallization of any single aspect to become the poem’s fulcrum. Walker-Figueroa’s tool chest contains many poetic maneuvers, but it is easily apparent that her favorite is juxtaposition. She places things in adjacency and lets the reader draw their own conclusions.

This juxtaposition takes center stage in the first two poems: “Philomath” and “Permission to Mar.” Here she stacks heaven and hell against each other along with the internal and external, constructing a thorough and explicit picture of her childhood: writing her name on the walls in crayon, knowing better than to watch her friend’s bulimia firsthand, witnessing the aftermath of addiction, watching a town sink into itself, the river carrying all things forward into tomorrow.

Walker-Figueroa shows herself to be a master of the poem never being about what the poem is about, often because of said juxtaposition. Not necessarily due to metaphor, but because the panorama of each poem offers too many views for it to ever only be about one thing. My favorite example of this occurs in the poem “After Birth,” where she recounts being told how cougars seek out the placentas of horses after they’ve birthed foals. The poem pretends to be about sexual violence at first–and by that I also mean the violence imposed by norms and policing of “sex”–but it is really about being a late-bloomer and the self-doubt that characterizes growing up:

all I can think of is blood, how we first feed

on it without knowing

we feed on it or that it possesses a plan all its own. Every girl

I know has started, nicknamed it

Florence or Flo or the Red Badge of Courage. It’ll be years

for me. When a doctor finally says I’ve fallen so far

off the growth chart he’s worried

I won’t find my way back, I’m fourteen

& can still go out shirtless

without causing a stir. “Eat more butter,” he says, but I don’t

yet believe what I eat will help me hate

my body any less. Reed doesn’t hate

his kids. He loves them too much is the story. People tell me

to avoid him, but I don’t.

Philomath is riddled with moments that make themselves aware of our Anthropocene’s extinction events and progressive societal dilapidation. There is a grappling that ensues—how to deal with personal pain amidst public and pervasive suffering, something becoming a hallmark of contemporary poetry delivering a cultural critique. It is important to note however that this book is not merely a compendium of suffering. The characters lead textured lives and there is a wild abundance of tenderness:

She loved nearly

any animal that wasn’t

cut out for living—like

orphaned fawns & withdrawn

addicts she’d find

trembling at rest

stops along Route 20, like cedar

waxwings that mistook glass

for the space that lives

behind glass. Under the last

incense-cedar in the back

yard, we had a whole

boneyard of birds—

Toby, Thelma, Obadiah. We didn’t know

their sex. We didn’t know

why they camped all winter

long when they had bodies

that could carry them

some place warm & somehow full

of promise.

It is a complicated message the book delivers—the need to escape a place that is consuming you and the ones you love coupled with the desire to rescue said place from itself. The questions posed here are not moralized or truly ever answered. And as much as they are questions about the purpose of grief, they are also questions about why people stay in a place that is hurting them. Sometimes it is the only thing they understand. Sometimes for other people. Sometimes they desire the breaking. What is clear is that even in leaving the places we’ve rooted ourselves, they remain with us always:

I wonder when

it began, the belief

that the part of us that’s always been

dead keeps growing after what we call

life has left the room.