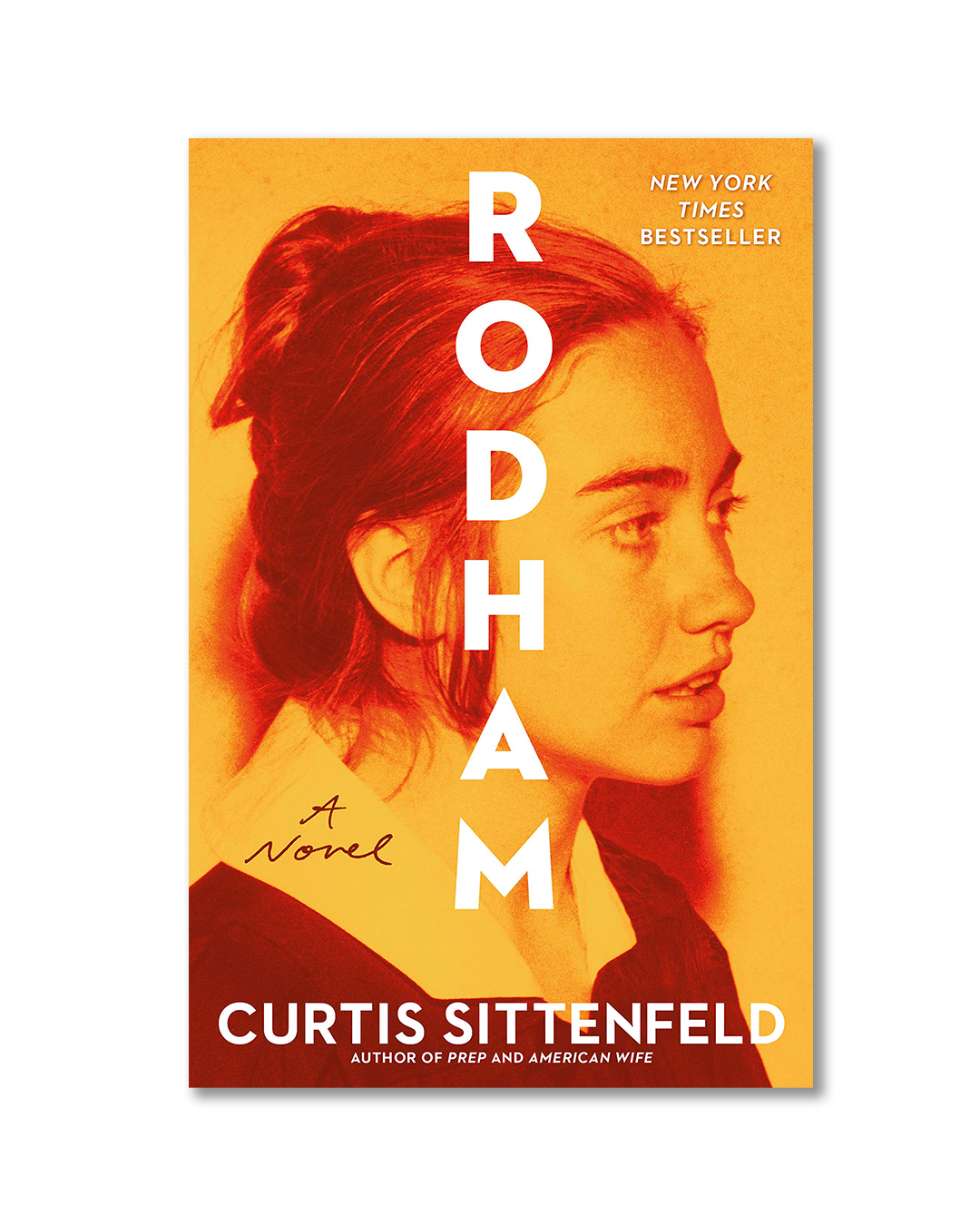

Barely a Victory: On Curtis Sittenfeld's "Rodham"

Curtis Sittenfeld | Rodham: A Novel | Random House | 2020 | 432 Pages

Fiction seems to be the only way to move forward with an investigation of Hillary Clinton. The true Hillary has been so thoroughly dissected over the last several decades that there’s simply nothing left to say, unless you want to begin making things up. And I’m glad Curtis Sittenfeld did, because I’m not bored of Hillary yet. In Sittenfeld’s Rodham, Hillary Clinton, now reimagined without Bill, succeeds professionally in a way the real Hillary did not—she becomes president. Set free from the public humiliation of her husband’s misdeeds, one of history’s most famous women charts her own course. Sittenfeld effectively swaps out the two most public aspects of Hillary’s story—her marriage to Bill and her 2016 campaign—to reframe her life,

Sittenfeld does an impressive job of hitting the tone of a political memoir. She includes specific parallels to Hillary Clinton’s own political memoirs, such as a scene in which Hillary first meets Bill’s mother. It’s not a diary; absent the sex scenes, it could easily be a book a politician would write. For example, when her Hillary gets criticized for undermining Carol Moseley Braun, a Black Senatorial candidate, who, in real life, became the first Black woman to serve in the Senate, her response is standard spin. Not all the characters are historical figures—Sittenfeld invents several of her own, and while she researched the real Clintons thoroughly for the book, she explained that she believes the number one goal of a novelist is to tell a compelling story. The book blends delightful story-telling skill with enough historical references to keep the most devoted political-junkies satisfied. However, the tonally appropriate political memoir style keeps us at arm’s length from her fictional Hillary, whether by design or not. I didn’t feel like I knew Sittenfeld’s Hillary well enough to separate her from the real woman.

Perhaps it is this inability to completely separate the real from the fiction that makes the ending so unsurprising—not because it seems like the logical outcome for the real-life Rodham had she not married Bill, but rather because the most public failure of Clinton’s life seems a natural jumping off point for our 2008 and 2016 fantasies. Sittenfeld may have left out Rodham’s vote on the Iraq War, but we’ve all spent enough time fantasizing about a Hillary-presidency that our preconceived notions win out. I found myself unsatisfied by the ending because it was too mired in my beliefs about an actual Hillary Rodham presidency. Would a white woman from a powerful political family really cure all America’s ills? The ending is less of a tidy victory for women than it would be with a fictional protagonist. Perhaps with a completely fictionalized woman, we could have suspended our disbelief and celebrated in an uncomplicated victory for women.

However, it’s not merely that the ending doesn’t seem like a victory for women—it barely seems like a victory for Sittenfeld’s Hillary. She doesn’t marry or have children, and she loses the self-described love of her life—Bill. As she describes Obama’s victory in 2008 (very little actually changes, much to the chagrin of chaos theorists everywhere) she says, “What, I wondered as Sasha clasped her father’s hand, was it like to get both, to have a family and be elected president?” On the one hand, this line is a hilarious reinterpretation of the “can women have it all?” question exclusively from Rodham’s perspective, where success narrowly defined (did you or did you not become President?). On the other, it sets us up to believe the novel’s Rodham will be forever unsatisfied; she never gets both. At the same time, Sittenfeld asks us not to feel sorry for her: “If being president is necessarily lonely, I am less personally alone than I’ve been for much of my adulthood.” She even gave President Rodham a boyfriend, and yet, “less alone” barely sounds like the ringing endorsement you’d want from a woman who achieved her life goals. I desperately want to believe if it had gone another way, she would have been happy, but I don’t.

Rodham is an ambitious undertaking—Sittenfeld chose a narrator the reader already knows. But if you’re not bored by the Clintons (and I know many people are), you won’t be bored by this book. It’s witty, insightful, and difficult to put down, and the timeline is so realistic we feel like it’s modern history. Bill Clinton runs for President in 1992 but loses. Obama becomes President in 2008, and Hillary in 2016. Vox fact-checks the likelihood of events, if you’re curious. For me, the realism of the political milestones only served to further conflate the fictional Hillary with the real one. As much as I tried to avoid it, I found myself comparing the protagonist at the end of the novel not only to her character in the beginning, but also to the real-life Hillary.

My reaction to the ending forced a confrontation with my own internalized misogyny. Did I not believe a woman could be happy without the perfect family? Well, if not a perfect family—the Clintons. Am I so convinced motherhood is the ultimate goal for all women that I really believe Hillary wouldn’t trade in her only child for the country’s highest office? I would rather get married and have children than become President of the United States, but that’s because I really, really don’t want the job. Sittenfeld exposes the ways in which Rodham’s life stays sad, despite her professional success, as Bill breaks her heart again and again. With each new run-in with her ex, I pitied her. And then, I pitied myself for pitying her. Shouldn’t I be able to believe Hillary was happy as President? When it was over, I didn’t believe Hillary’s story had fully resolved, although this issue is as much mine as Hillary’s. Maybe I just didn’t buy into the simplification of Rodham’s goals. Or maybe I just can’t picture Hillary happy.