The Space to Become Oneself: On Crystal Wilkinson's "Perfect Black"

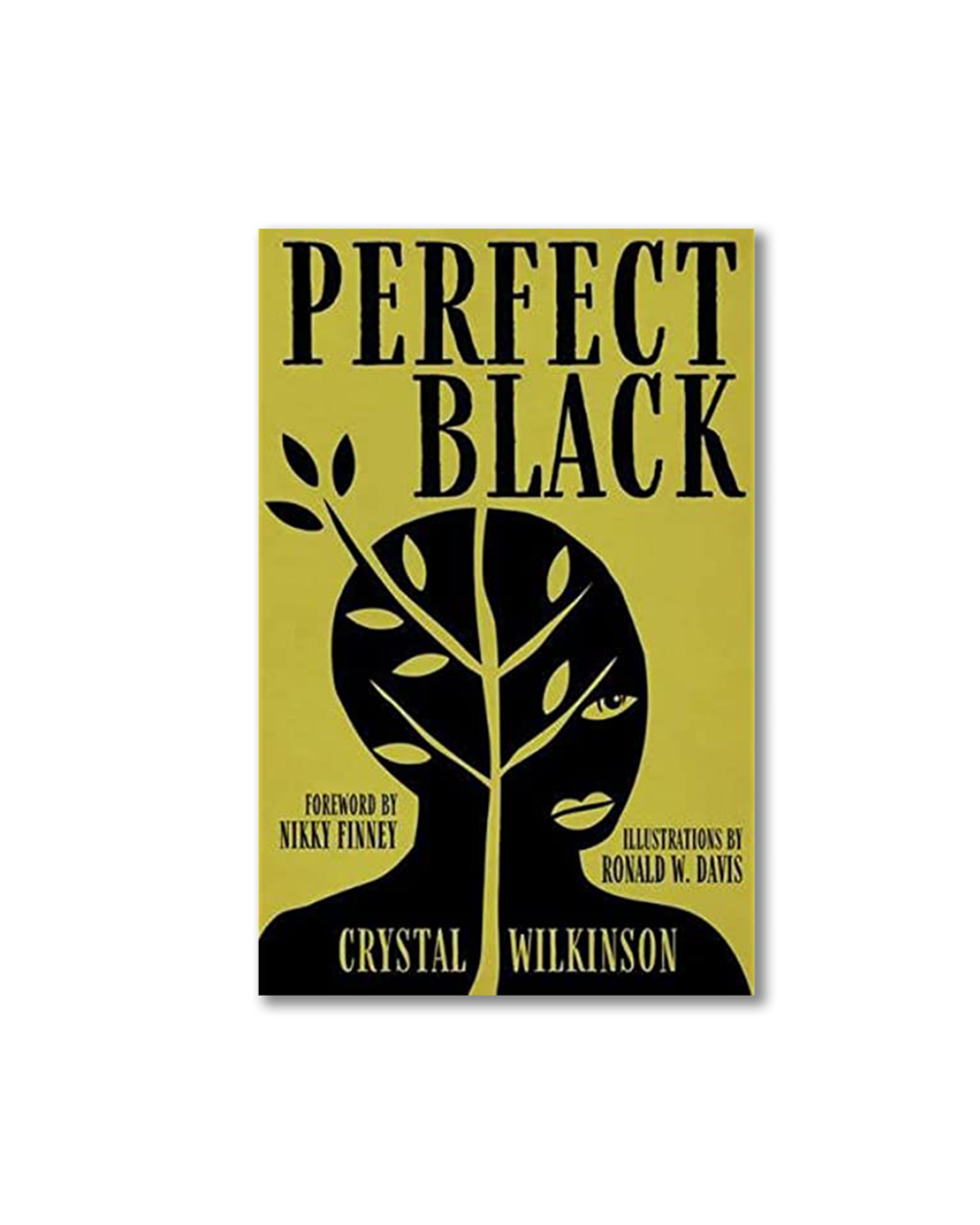

Crystal Wilkinson | Perfect Black | University Press of Kentucky | 2021 | 96 Pages

Perfect Black is the long-awaited first book of poetry from Kentucky’s Poet Laureate, Crystal Wilkinson. The work in this collection was written over many years—a fact that makes itself evident as these poems offer intimate and detailed snapshots from different stages in Wilkinson’s life. In an interview with the Southern Review of Books, Wilkinson says, “I hadn’t really planned on writing a memoir in verse, but a lot of the poems that were heavily threaded with topics that were more away from me or in styles that were more away from my truth began to thin out”. Through the act of winnowing down a larger body of work to produce this manuscript, Wilkinson has zeroed in on what fellow poet Nikki Finney, in her introduction to the book, calls “the terrain of black girl becoming”. That terrain is physically rooted in the landscapes Wilkinson has occupied her entire life—especially Appalachian Kentucky—and this emphasis on the land itself within Perfect Black brings with it a shared emphasis on embodied experience. Through these points of emphasis Wilkinson crafts a memoir in verse that, rather than being focused on detailing a linear narrative of events, is concerned with representing the development of her own consciousness, personal growth, and interior life—an ongoing process of becoming herself. In doing, so Perfect Black paints an intensely variegated and intersectional picture of life as a Black woman growing up, coming of age, and maturing in Appalachia.

The term “Affrilachia” was coined by Frank X Walker—former Kentucky Poet Laureate and Wilkinson’s current colleague within The University of Kentucky’s English department. That coinage arose after Walker read a definition of “Appalachian” that said, “white people indigenous to the Appalachian region”. A Black writer from the region, Walker recognized immense gaps within the dominant cultural narratives surrounding Appalachian life. Thus, the Affrilachian movement was born. The concerns and aesthetics of this movement have had a pronounced impact on Wilkinson’s writing. In an interview on the podcast Reading Women, she says, “what it did was give me a place, a sense of belonging. A place where my back could be straight about all the pieces of who I am, about my Black self and my rural self and my country self and my Appalachian self, in one place”. Perfect Black, in the spirit of the Affrilachian poetic tradition, makes a mission of continuing the act of carving out space for Blackness within a geographic region whose cultural narratives are overwhelmingly dominated by white stories and perspectives.

The collection’s first poem, “Terrain,” makes clear through its title the role that physical landscapes play in constructing a sense of self. Wilkinson writes, “still I return to old ground time & again, a homing blackbird destined to return. I am plain brown bag, oak & twig, mud pies & gut-wrenching gospel in the throats of old tobacco brown men”. In these lines, she highlights the ways in which her personal consciousness exists in a co-constitutive relationship with collective Black experience. That consciousness is shown to be inseparable from the landscape, as Wilkinson’s first-person address interchanges physical objects like “oak & twig” with cultural traditions like “gut-wrenching gospel,” claiming that they both make up who she is.

As the collection progresses, Wilkinson plays with voice and narration. This is especially evident in a trio of poems that all begin with the phrase, “The Water Witch.” One is left wondering if the voices in these poems are, perhaps, representative of Wilkinson’s grandparents (farmers who raised her in Appalachia); however, the speakers might also be seen as embodying a more generalized sense of Affrilachian voice and experience. But despite their shifting perspectives and possibilities, these poems ring true to Wilkinson’s individual experience. They help to expand the reader’s understanding of her life as a Black person in Appalachia by representing a wide range of experiences and dialects in this place—things that, being rooted in tradition and the land, are in Wilkinson’s view intrinsic to her own identity. In the first poem of the three, “The Water Witch on Salvation,” she writes, “when the horses took off with the wagon / & my grandbaby inside, I chased it. / My legs nigh on seventy, moved like a lightning twenty-- / down the bank & across the pasture, I hollered out, Hah up now!”. This technique of writing Affrilachian dialect carries through to the next poem, “The Water Witch on Invasion.” Here, Wilkinson writes, “Sometimes / i turn the light on, so i can see who their daddies are. / Young white boys are like that sometimes, smelling / their selves, thinking they can do it cause i’m black, / cause i’m old, or just cause”. Language is a window into culture and lifestyle. Wilkinson, through her approach to crafting a memoir in verse, centers language in the form of Affrilachian dialect to capture a way of being in the world, a particular identity that has gone overlooked—Black, rural, Appalachian. As she writes in another poem in the collection, “On Being Country,” “Country is as much a part of me as my full lips, my wide hips, my dreadlocks, my cheekbones. The way the words roll off my tongue is the voice of my people” (62). Earlier in the same poem she describes how, for the longest time, “being and talking country, having a twang in my voice, became something to be kept to myself”. It is only after claiming her heritage, her pride in her identity as a Black Appalachian woman, that Wilkinson is fully empowered to become herself as a writer.

We see increasing focus on Wilkinson’s aging and maturation over the course of the book. However, as Finney notes in her introduction, “this is not a linear story. This is aboriginal understanding. This is fragmentation and this is how black people hold on in real life”. The fragmentation of Perfect Black’s narrative serves to represent the present’s infusion with the past, as well as the self’s infusion with the other. In this way, Wilkinson crafts an aesthetic representation of intersectionality, of the co-constitutive nature of all aspects of one’s identity. The importance of this aesthetic becomes even clearer as the book proceeds. A particularly powerful example is the poem “Dig If You Will The Picture” wherein Wilkinson writes, “1979. THE WHITE BOYS at school extended their hands into the aisle when I boarded the bus in the mornings. … Their hands taking what was not theirs. ... The white boys laughed. The white girls laughed”. The racial and sexual violence Wilkinson faces in these lines can only be fully understood in the context of the legacy of slavery, systemic racism, and patriarchy in America, and their prevailing effects. At the same time, one must understand that such systems of oppression are not discrete but interlocking, that they help to uphold each other—a fact distilled by their simultaneous exertion upon the speaker in the lines above. The best way to represent these effects, for Wilkinson, is by focusing on the particularities of her own lived experience, charting these forces in her own life.

But in demonstrating the oppression she has faced for simply being who she is, Wilkinson also claims her identity for herself, celebrating its beauty. In a poem titled “Black & Fat & Perfect,” she writes, “He scoops her waist from behind, / cups the girth of her belly & she is black & fat / & perfect in his capable, warm hands”. Wilkinson’s act of becoming is ongoing, rooted in a history that is ever-unfolding—one that she has an active role in creating. Reflecting on the sense of peace and autonomy she feels in her partner’s and family’s eyes, Wilkinson moves us, by the end of Perfect Black, into a beautifully meditative space—one that is aware of the many interlocking histories that make up a self, as well as that same self’s potential for making new stories, for continuing the act of becoming. She writes, in “Coming of Age,” “I am moving toward an age of comfort / full of remember-whens / enjoying my mother’s reflection in the mirror” (71). With Perfect Black Wilkinson helps us, as readers, to take a closer look at our own reflections, as well as those of others we meet, asking us to slow down, to take note of the hidden histories all around us, and to recognize our own potential to make them anew.