Mired by Monolingualism: On “The Autobiography of a Language”

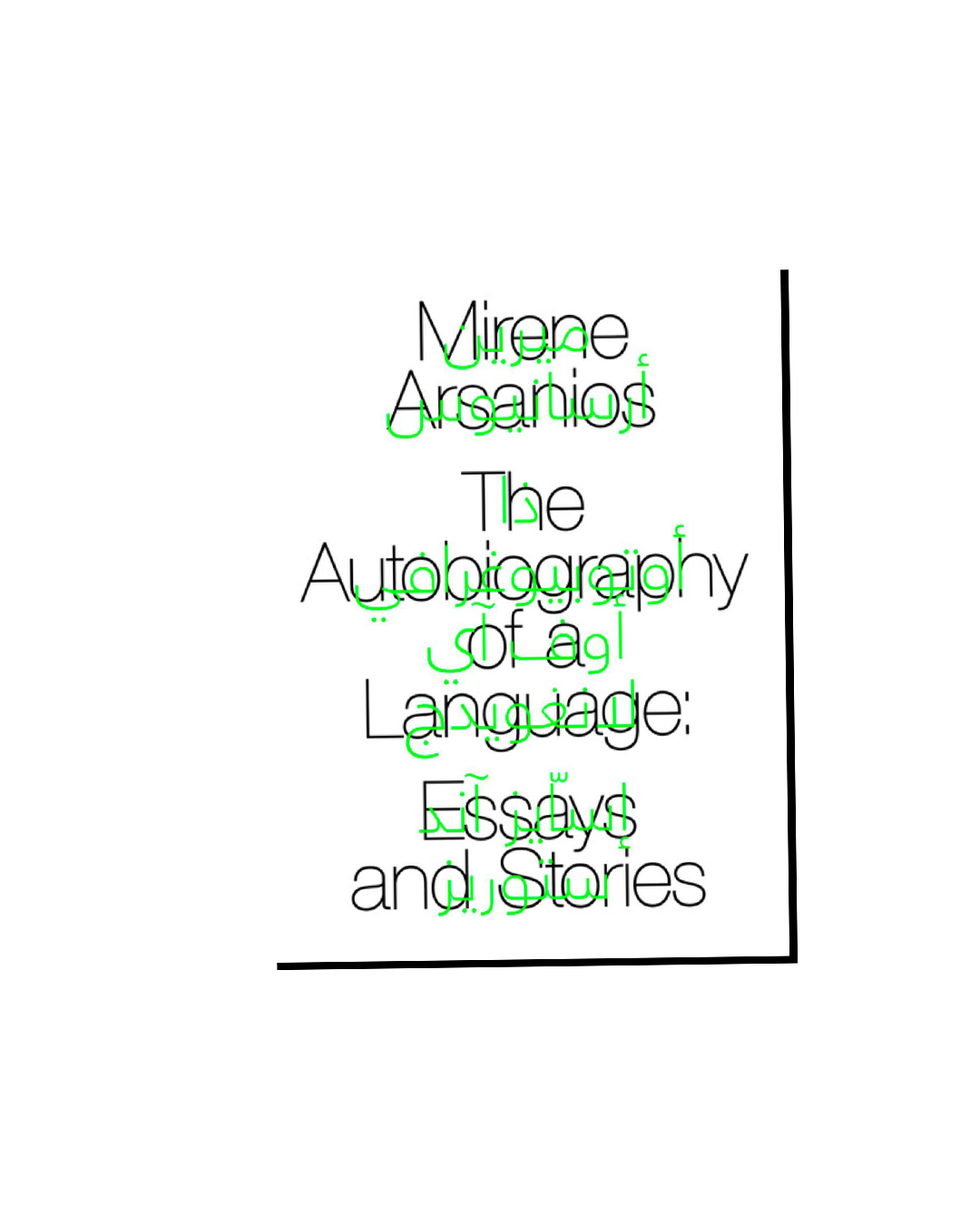

Mirene Arsanios | The Autobiography of a Language: Essays and Stories | Futurepoem | October 2022 | 91 Pages

This past summer, I left the United States for the first time since 2019, and found myself amidst a newly-engineered European politics. At the border of Italy and France, my US passport was taken for a short time due to my Ukrainian birthplace; a visa was briefly requested. In Marseille, I forgot how to speak—a headful of words and phrases, none of them French, and none of them “mine.” A body uttering English, yet physically placeless. The United States claims me: I snuck into its crevices in the thick of the global crisis of the aughts, the nineties, the eighties, the fifties; the everlasting Cold War era. This claim is now an allowance to exercise my bodily autonomy to cross borders. This claim is an ownership of my body.

In her 2022 collection, The Autobiography of a Language, Mirene Arsanios writes: “At the nexus of citizenship, individual rights, and monolingualism, there is ownership: of self and others.” The book is a blended collection of stories and essays; specifically uncategorized and rife with genre-crossing.

•

To write an essay is to make an attempt. “To essay,” etymologically, derives from the phrase “to put to proof, to test the mettle of.” What is being attempted here? In this essay collection, the attempt is to dissect and restitch language into a porous form: it is interrogated, at points, abandoned, becoming beyond. Arsanios is exploring a fragmented relationship to language and its multiple beginnings through a defiance of both fluency and singular origin. This being an autobiography, the speaker of the book, the “I,” is a language; a language whose stories and essays tumble out into the page, whose roots are many, whose roots have turned rhizomatic in the lacerated land.

Language stays, yet it leaves. It wants to stay—to be present—but it is whisked away by emergencies conducted in a globalist empire we call a world. Language betrays. And is betrayed. It desires autonomy, a movement away from a focal point to allow itself practices in newness, modernity. Yet it is also beholden and held by tradition, a local, a locality, the historical context. Language is kissing boys in an Italian garden. Language remembers. Language distrusts empathy. Language is a dutiful daughter with a desire to stay true to family obligations. Yet language continues to break away, exist on an axis, the threshold, like language’s mother, who yearns for “fresh fish and guava juice” from Caracas, laying on her deathbed a continent away.

“Where does she live now?” asks an unidentified man in The Autobiography of a Language.

“On photographs printed in pharmacies and forgotten on checkout counters. She died of an American illness,” language responds.

Language and its affiliates, family members, its past and present, become emblematic depictions in Mirene Arsanios’s essays—advertisements for an alternative outcome, what can be healed, bought. They offer inspirational anecdotes for ordinary people and instructions on how to be a good citizen of a nation state: a public service announcement for the health and well-being of the national collective. Language becomes a propulsion of the state and its objectives. The body, a form of its ideologies, carrying out potential principles in daily events, incidents. “Are incidents outcomes of history?” Arsanios asks.

When language leaves its family structure and moves into the academic institution, or when language is confronted with the magnetism of coloniality in a space of monolingualism; when the power of tongue, of legitimacy, of essence is deteriorated by institutional upholding, language begins to question: what does a lineage pass down? “Losing what you most desire accelerates the shedding of reactionary ideologies, but what if you got what you wanted?”

Language, itself, narrates:

I feared that by connecting mothers and language, Woolf was summoning the sanctity of mother tongues, normalizing a biologically sanctioned bond in service of the monolingual nation-state…I wrote papers on separating language from biology. What about those without mothers or those disengaged from daughterhood when it entrails the reproduction of patriarchal, patriotic narratives? There are other types of lineages: broken, colonial, different acts of (non) storytelling—generational tales in which transmission are withheld and beginnings arbitrary.

Arsanios lives deep in that language which fails. “My body began to sink, I wasn’t able to see or move beyond the sentence,” she says. Language becomes a rehearsal; a mimicking of a stubborn efficiency.

•

In February of 2022, I found myself on the fringes of a national tragedy, which has extended far beyond the borders of Eastern Europe since the 1990s. I was born in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. I grew up speaking Russian. I continue to speak Russian. I once spoke Ukrainian. I have since forgotten Ukrainian, having replaced it with Spanish—a necessity borne out of living and working in the United States. Ukrainian lingers in my memory, but not strongly. It has never completely left; it has no place to go, just mingling with the others in the back room of memory. Recently, Russian has become the language of invasion. It’s a language not so far away from Ukrainian. These languages are kin; overlapping in vocabulary and structure, but diverging in pronunciation: Ukrainian, it is said, is more melodic.

What happens when a childhood language becomes the language of an oppressor? “The lines separating oppressor and oppressed keep shifting and begin from within. Europe against itself, Europe on the brink of its own implosion.” My mother asked me recently if I could pronounce паляниця, a particular type of Ukrainian bread—currently the Ukrainian military shibboleth. This pronunciation is alibi.

What language do I even speak? “‘Syntactically, you’re strange,’ the man adds, ‘Disjointed like a body,’” I read in Arsanio’s pages and nod along.

I cannot pronounce паляниця, as its tongue structure has disengaged from my familiarity. The softness in the middle of the word is gobbled up in my mouth, transforming the hardness of the third syllable into a soft-boiled mash. The key of the word lies in its balanced dissonance of sounds. I mix up the hard ы with the soft и in Russian; in Ukrainian, the и is hard. I still stumble in English. I often forget words and ask my students to help me remember them, deflating my performance expectations. We’re learning together. At times I settle for imprecision, rendering the luminosity of my polyglot individuality as a collection of scraps.

Eduard Glissant, who, in his exploration and call for opacity, or a relation based on difference, criticizes a monolingual communication: “Although language doesn’t pose a direct threat to the environment, certain forms of monolingualism continue to dehumanize and extract land and resources from those who aren’t included in it. Such national-territorial-languages are a threat to the planet’s ecosystem.” As though in dialogue with Glissant, Arsanios continues:

“Historically speaking, the congestion of the nation-station and monolingualism is relatively new. The mother tongue became an instrument of national and territorial cohesion in the late 18th century…What has come to be considered an anomaly began through a process of national engineering in both colonial and colonized nations.”

She denounces a state-sanctioned monolingualism aiding borders and supporting land ownership. To be inducted into a nation’s membership one of the requirements is to speak the state-sanctioned language, which in turn upholds the national ideology and epistemological framework. This divide in language is also a component in missile launches across borders to gain more land and area to add to its mass; not unlike Russia’s current invasion of Ukraine.

How to find home within language’s scarred territory?

I continue to ask questions. To be left with them.

•

This book is full of questions, too. Arsanios makes a point against the value of monolingualism, yet an inquiry remains: the questions of possibility. She never fully decries language nor narrative, but rather probes its mutating and challenged form. “If I had a child, I would address them in a bastard language, a combination of those available to me—Arabic, French, Spanish, English, Italian—all existing in the mix of my inflections, with no language truly taking precedence over the other,” she states, invoking the subjunctive.

In language’s errant state it has reached a kind of borderlessness in the age of globalization; living a risk and a potential, continuing to overlap with its neighbors. Such as the usage of English, which “seamlessly meander[s] continental distances. I never considered this language to be my own. I do not hate it. I do not love it. It is incidental and life is made of circumstances, outcomes of unruly trajectories,” she proposes, opening up a probability for a wandering and unfixed future.

I find myself intrigued by my use of English, how often I am changed by it. How it stakes its entitlement. My immigration, an artifact of the Cold War. My return, incomplete, unviable. Yet English often changes form through my ordinarily ungrammatical inflection and syntax—my desire for fragment sentences, the passive voice. “I feel environmentally wasteful when writing in English, a language whose proliferation is killing so many others. But I’ve found a voice in English, a language in which the self, through its assertion, is continually deferred, and in which monolingualism gives way to a multitude of idioms and dialects that become languages of their own,” Arsanios writes as the narrator that is language. Perhaps in the usage of English, gaps form: to be filled, emptied, and filled again with plurality in dialogue. With each new introduction of a language, the form must change and morph, slowly altering what was once considered known, complete; as language does in its autobiography.