Antagonistic Forms: A Conversation with Quenton Baker

Quenton Baker | Ballast | Haymarket Books | April 2023 | 150 Pages

Some only really talk about the top

But I wanna talk about the bottom

—Lupe Fiasco, “Down”

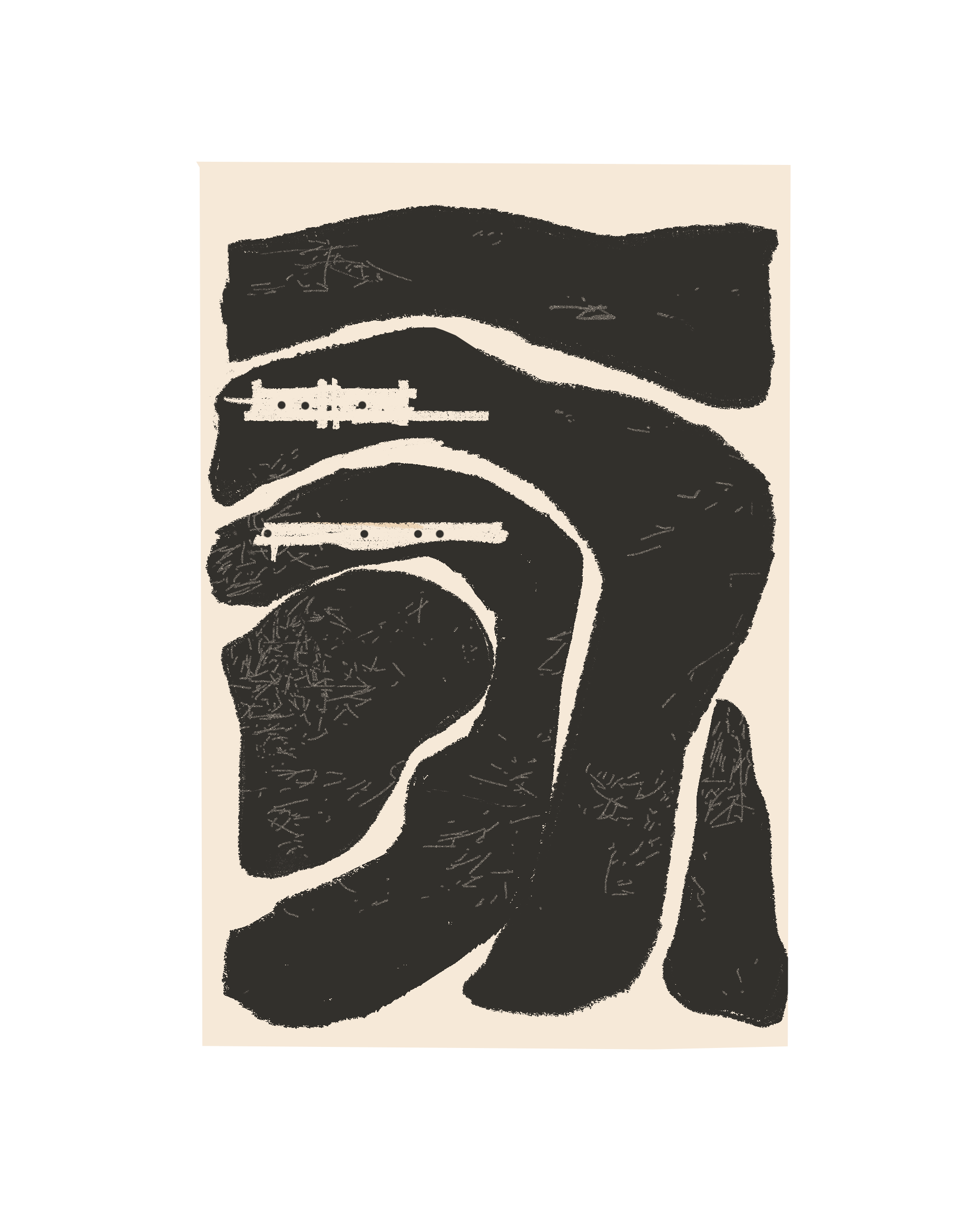

In November 1841, a small group of American-born slaves aboard the ship Creole led a mutiny, forcing the crew to sail to the Bahamas where they disembarked. This is where Ballast begins. While most erasure—or blackout poetry—erases or obscures existing text to make new meaning, this text implodes the record to remember what was there all along. Composed of an epic erasure and long poem, this tour-de-force spans the large-scale revolt aboard the Creole. Nearly 200 years are brutally, needfully collapsed to bear witness to the tenderness and terror that co-constitute Black life in the world—the world that slavery built. As impending climate collapse draws our attention to the force of the seas, Ballast begins on the Atlantic—where the life and death of Blackness begins and cannot end. With their expansive, addictive diction and attention to the ceaselessness of history, Quenton Baker materializes “a terrigenous ontology / a ship full of continental theft and collapse / this catalyzing sea.” And in its most exciting turns, Ballast crafts new, unnerving language for inhabiting and describing a doomed double consciousness: to know that one’s being is a fiction maintained to exert dominion over you and everyone you love, and to be still. Or, as Baker writes:

we write the field open / while buried beneath it.

How and why might a Black person acknowledge the existential necessity of their subjection and proceed to make shit? Can the art we make cease to reproduce the world that made us, and to what extent can it avoid the amnesic and individualist politics that authorize Black self-making? I left my reading of Ballast awash in these questions, a testament to its deep engagement with Black Studies and literary attempts at staying with, and making clearer, the need for anti-Blackness in modernity. This work demonstrates that language cannot redress ontological violence, but can, perhaps, render it.

In March I met with Baker. We discussed retribution, realizing that you’re dead, and reading Saidiya Hartman for the first time.

This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Jon Jon Moore Palacios: So you learned about the Creole revolt and were in the archive looking for material evidence. What else were you looking for?

Quenton Baker: I think the answer to that question is also the answer to another question: Why study chattel slavery at all?

In 2014 I had just finished what would become my first book, This Glittering Republic, and there was something burning inside of me. I was deep in research on the coastwise slave trade. When I first went into the archive, I really didn’t know what I was doing. I wanted to write a linear, historical telling of the Creole revolt. I don’t know what I was looking for or what I was trying to find or accomplish, but I wanted to hold something that might propel the writing forward. I wanted to find something that I could possess. What I found, though, was the absence of speech in the archive—there is no recorded speech of the slaves who revolted. What I was looking for could never be found, so in hindsight, what I was probably always looking for was confirmation. I wanted to make sure that everything that wasn’t there . . . wasn’t.

JJMP: This idea of looking for confirmation . . . it’s really fucking me up. Two years ago I found the cemetery where my great-great-great-grandmother was buried in Chicago. Her birthplace is recorded in the 1850 Slave Schedules as Africa. I went looking for her gravemarker. And I’m in the rain walking back and forth through rows of graves before it occurred to me that I would be unable to find it. Why would it be marked? Just because this was the last place she was seen? To think I would find her there . . .

QB: Yes. Because who’s gonna mark the grave of property? This is something that I had to learn, and it takes time to think through.

JJMP: You found what wasn’t there. Then what?

QB: I went to the archives before I read Scenes of Subjection (Saidiya Hartman, 1997). I was dealing with an overwhelming set of emotions—I was mad, and I immediately realized how fucking stupid and impossible my desire or ability to tell this story was. I didn’t know this when I was writing my first book, but I think that as a Black artist if you don’t have a theoretical framework, a way to orient what you’re doing, you’re probably fucking up . . . reproducing trauma, reenacting subjection. But I found Scenes while reading Fred Moten’s In the Break and I spent a year reading it. I finally had a framework for beginning to understand what slavery actually was, and is. And Saidiya led me to Christina Sharpe, Hortense Spillers, Jared Sexton, Calvin Warren, Alex Weheliye, Simone Brown, Frank B. Wilderson III, Michelle Wright. Black Studies gave me more.

JJMP: The first part of Ballast is an erasure of a U.S. congressional document from 1842. It is mostly depositions from crew members of the Creole who survived the mutiny and letters between consulates. But you’ve mentioned that before working on this erasure, you weren’t really feeling erasure as a form.

QB: I’ve never really been a poet who embraced poetics as play. Not a bad thing, I love Harryette Mullen’s serious play. But when used by non-Black poets, nine times out of ten I’m like . . . y’all just being cute. Maybe it’s visually appealing, but even when it’s striking against the authority of some imperial document, it often boils down to a hunt for fragments to spell whatever you want. But, someone told me about M. NourbeSe Philip after seeing some of my early erasures, and then I read Zong! and saw what was possible. Alongside Black theory I was reading, the poetry and the notanda helped me understand what erasure was and what it was doing. And I came to think about erasure as an allegorical form. Blacks live in an anti-Black world, right? And in the United States, we live within the country that enslaved us. Every single fucking thing in this country is going to be built on Black people. So, underneath the government and the government’s speech, all of its ledgers, there is a language under language. We may speak in a language that is the same language that obliterated and obliterates us. And, we find a way to speak English within English that isn’t related to the English that harms us.

JJMP: This language under language . . . how did you get at it or attempt to with erasure?

QB: I felt like there were rules. There are no rules, but when working with this text I felt that there were rules. For example, I’m only going to use whole words. None of the lines will be really long. It felt like a practice of being as non-indulgent as possible.

JJMP: And that’s funny to hear you say because, some people are going to read this book and be like, “This the most indulgent shit I’ve ever read!” Maybe I was one of them.

QB: Maybe.

JJMP: We do not hear from slaves in this document, and when their names appear, it is the last time we see them, really—they disappear from history. But then you get your hands on it, and you’ve described what you’ve done to this text as “retribution.” Why?

QB: I knew I could never locate or approximate speech or take up the position of the slave, and I was not interested in projecting agency backward to the slave. But I thought that if I hit this fucking text enough, something might fall out. I thought maybe I could hear something else, some type of echo that made sense to me. And if not, revisiting the same type of erasure upon this document that it enforced and enforces upon the 135 slaves that were in the Creole and Black folks everywhere—this would still make me feel better.

JJMP: Ok so, on my Christina Sharpe etymology tip, I had to look up the definitions for “retribution.” And payback is one. But I love this one: “the dispensing or receiving of reward or punishment, especially in the hereafter.” We are living in the hereafter and there’s something spooky about the intimacy of punishment and reward in this definition and in Ballast.

You wrote in the coda that you wanted to hurt this text, but you are also in the text as you are attacking it. This is the antagonism. Can you talk about how it felt to exact these erasures? What did you learn along the way?

QB: There were distinct phases in the erasure. In the middle of writing, I had an exhibition in the Frye Art Museum in Seattle. I was physically painting these redactions on ten-feet-high sections of vinyl, and in the lead-up to this, I’m experiencing rage and anger (which I think are different) and I’m feeling purpose. At this point I wasn’t blackening the text, I was using White-Out.

JJMP: Like office White-Out?

QB: The little bottle you use for documents.

JJMP: Stop.

QB: Yes. And surfacing this language in a sea of white was absurd. But also, I found that what was coming out when I was using this tiny ass brush was more narrative, it wasn’t what I was looking for. It felt like it was me doing it. Then I switched to the black sharpie to redact and it felt heavier, sort of like subterfuge and purposeful engagement for the first time. It was dogged, it was meticulous. And the anger became larger as I was installing. Again, ten-feet-high, all of a sudden this shit is physically big, and bigger than me. During a preview, these two white ladies came in and they didn’t know I was the artist, I wasn’t in front of it but I was in earshot. And one tells the other that it looks like a kindergartener did it, and that was confirmation for me.

JJMP: Confirmation of?

QB: A visible but intelligible rage. “Angry scribbles” as she put it. I was like, bet. Good.

JJMP: And what is the difference between rage and anger for you?

QB: There’s a temporal component. To me, anger is the thing that I feel before I’ve decided to act, or as I’m still deciding how I’m going to act. Rage is what carries me through my decision—it’s anger put into action, put to use. There was a planning stage for each page, each redaction. But the rage is what carried me through the physical act of erasing the text with a certain . . . thoughtlessness.

JJMP: A good kind of thoughtlessness, maybe. I spent a lot of time with this book on my first read because you’re foregrounding antagonism in a way that does not publish well. I find Ballast to be exhaustingly ambivalent and interrogative without forfeiting knowing, and that’s fucking work. I think it is hard work because for me, there is not much liminal space between the hold and the outside, the sharpie and the white-out. If you veer too much in one direction you become incapable. Or insufferable, no shade! But you are sitting with antagonism and ambivalence and taking your time. How did you get here?

QB: We’re back at Scenes. It beat my ass! That’s why it took me a year to read. Nobody wants to get their ass beat and at the end concede, “Yeah you were right.” Niggas like Friday because Deebo was wrong!

I was about thirty when I read it and by then I had my MFA. I’ve read some people, I’ve thought about some shit, I’ve been Black my whole life, so I know a thing. Scenes was like . . . No, nigga. You don’t know shit. Anti-Blackness is not an issue of education. And everything you think is working or will work—it is not, it will not. It was humbling and very difficult and a personal attack, frankly, to be told that everything I was doing in my poetics in my first book was wrong. But I was lucky to discover it when I did because the older and smarter you are, the more difficult that unmaking becomes. Nobody wants to be told that everything they think about a thing is stupid.

JJMP: And maybe it’s because you are bound to lose something when you admit to yourself that there is no solution to what has happened and will happen to us. Do you think you lost something in exchange for this clarity?

QB: The first two words that come to mind are education and chronology. It’s easy to think or feel or rationalize that this shit ain’t as big as it is—because you’re alive and other niggas are alive, right? You can chop it up, kick it. I remember thinking when I was younger and reading James Baldwin: something like freedom might not happen in my lifetime, but give the next generation the right information or the right resources and the moral arc of the universe will bend towards justice. No.

The phrase from Scenes that has stuck with me the most is “the enormity of the breach instituted by slavery.” This shit is so big. And maybe that brings us to the myth of chronology: linear time equals progression. No. There is no linear progression and we’re reproducing subjection again and again. We live in this ontological abyss, but also we exist. What the fuck does that mean? I don’t know. But I know what it means to lie about this shit, and I don’t want to do that anymore. I’m no longer interested in talking to people who, structurally, cannot hear me.

Quenton Baker is a poet, educator, and Cave Canem fellow. Their current focus is black interiority and the afterlife of slavery. Their work has appeared in The Offing, jubilat, Vinyl, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. They are the author of we pilot the blood (The 3rd Thing, 2021) and Ballast (Haymarket Books, 2023).