A Presence Solved by Its Own Absence: On Anne Carson’s “Wrong Norma”

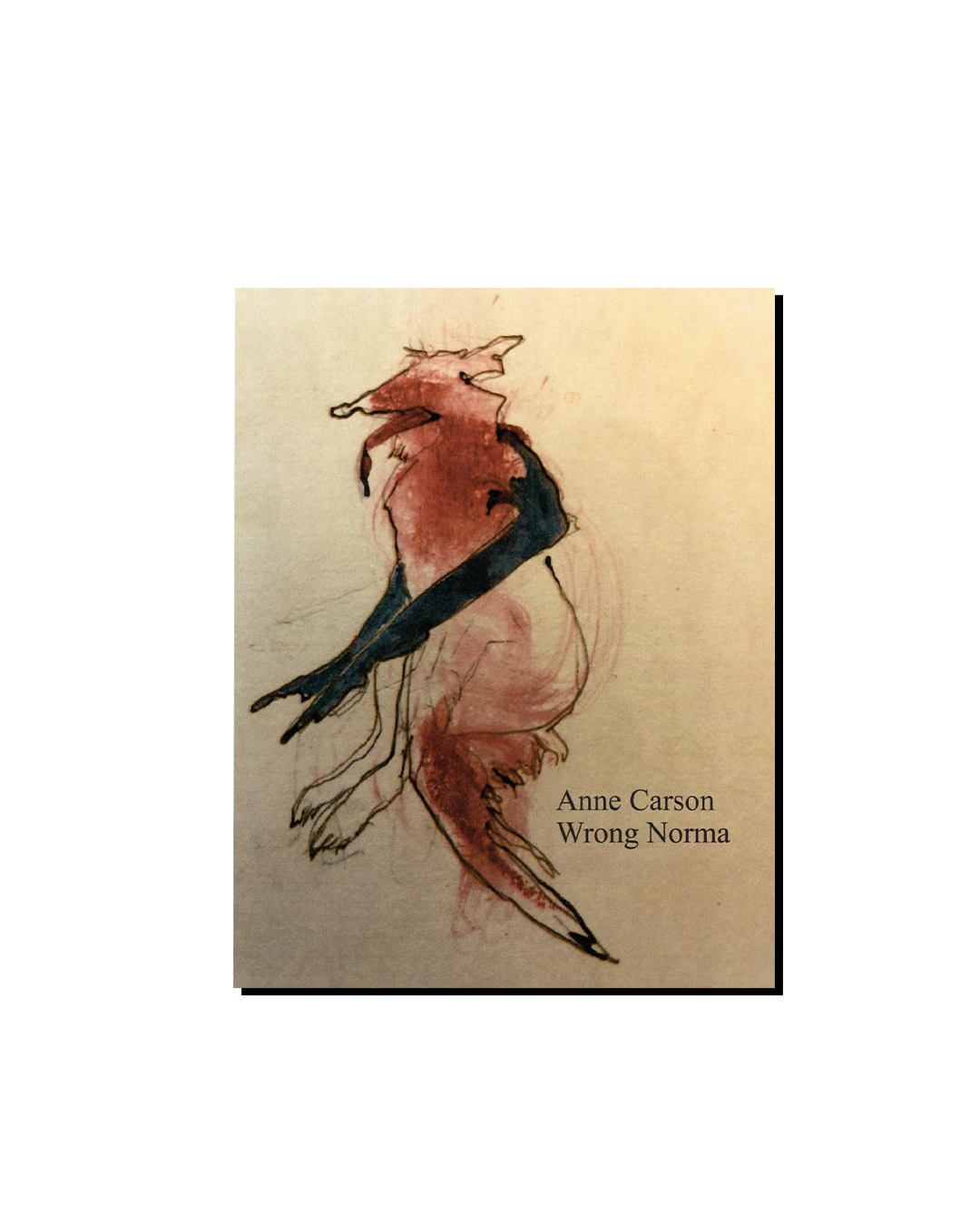

Anne Carson | Wrong Norma | New Directions | 2024 | 191 Pages

Something is rotten in the state of contemporary literature. You can smell it from a mile off—in the Poetry Foundation’s censorship of a review that espoused anti-Zionist views; in the Frankfurt Book Fair rescinding the Palestinian writer Adania Shibli’s award for her novel Minor Detail; in PEN America’s muted response to the ongoing genocide; in the canceled events for writers who have publicly criticized Israel. Reactions to such rottenness have ranged from open letters to resignations, prompting the age-old question: What is the role of art and artists in times of unrelenting political emergency?

Anne Carson offers a brutal response. “Poems don’t purify anyone,” she writes early on in her new collection, Wrong Norma. “There is a heap. It steams and stinks.”

This heap is in many ways the indirect subject of Carson’s first original work since 2016’s Float. Call it politics (crudely), the varied and various extent of human suffering (broadly), or perhaps the dim awareness that the material comforts of one’s seemingly atomized existence are inextricable from—worse, dependent upon—the routine maintenance of said suffering (slightly more precise). How to reconcile the presence of the heap?

No one would label Carson a “political” poet in any traditional sense of the word. Throughout her decades-long career, she has been characterized as a kind of oracle, both ancient and thrillingly modern (a 2016 interview in the Guardian chose the term “poetic guru”). In other words, her writing feels prophetic, in some way out of time. But what does it mean to feel out of time? Maybe the effect has something to do with Carson’s subject matter, which tends toward the scholarly and the intimate—mapping the precise contours of desire (Eros the Bittersweet) or beauty (The Beauty of the Husband) or grief (Nox). She is also genre-agnostic, if not averse, and complements her deep knowledge of antiquity—Carson is a translator of ancient Greek as well as a poet—with a freewheeling sensibility that can jump from John Cage to Emily Dickinson to the films of Michelangelo Antonioni in the space of a few lines. If political subjects do appear in her work, they come wearing the clothes of allegory.

Wrong Norma presents Carson’s first attempt to strip them bare. The results are mixed, but never uninteresting; occasionally they are sublime. Think of the collection as a synthesis, or a remix, of her classic toolbox. There are translations, short talks, dialogues, vignettes from Greek antiquity given a modern twist, and a variety of more or less narrative prose poems, in addition to literal collage. Two recurring pieces feature the typewritten questions “how do you sustain morale during a long project” and “what is your philosophy of time” over and over again, with responses that range from “Lutheran guilt” to “I feel like in a giant chestnut.”

We begin with a sort of thesis statement: “1=1”, originally published in 2016 in The New Yorker, describes an unnamed woman as she goes for a swim in a lake. “Every water has its own rules and offering,” the woman muses in close third-person. “Misuse is hard to explain.” Here we have quintessential Carson—readers may recall her lyric essay “The Anthropology of Water,” the final section of her 1995 collection Plainwater, which similarly employs the resonances and cultural significance of water as launching-off points for Carson’s meditations on (in that case) pilgrims, her father’s dementia, a temperamental lover. This time, however, the protagonist’s meditation is jarred by “front-page photos of a train car in Europe jammed floor to door with escaped victims of a war zone further south, people denied transit.” She steps outside, making awkward conversation with her neighbor, Chandler, an ex-convict who spends his days drawing on the sidewalk. When she returns upstairs, the woman once more contemplates “the failure to swim,” followed by the image of “certain refugees in a makeshift plastic boat.” What previously could not be thought (“she cannot think it”) now refuses to be un-thought. Well? The protagonist lets herself off the hook: “To be alive is just this pouring in and out. Ethics minimal. Try to swim without thinking how it looks. Beware mockery, mockery is too easy.” A pragmatist’s solution. One might also call it indifference, complicity, the desire to turn away.

•

The heap! Faced with the insurmountable fact of it—the “two mornings” of the swimmer and the refugees existing side by side—even an artist as singularly gifted as Carson may be tempted to forgo language altogether, which is after all so easily corrupted, subject to the winds and whims of history. Wrong Norma hums with anxiety about such atmospheric disturbances: “Sentences are strategic. They let you off.” “There’s fear in rules and stupidity in sentences.” “What do answers answer anyway. They fit onto questions like a stocking onto a leg but the bloodstains still refuse to evaporate.” “Flaubert Again,” a prose poem also published in The New Yorker, goes so far as to depict a writer who fantasizes about a “different kind of novel,” one that would reduce narrative to the singular and absolute—not a story, “just telling itself.”

Carson is by no means the first writer to be skeptical of her medium. Here is Susan Sontag writing about the burgeoning aesthetics of silence in 1967:

Up to a point, the community and historicity of the artist’s means are implicit in the very fact of intersubjectivity: each person is a being-in-a-world. But this normal state of affairs is felt today (particularly in the arts using language) as an extraordinary, wearying problem.

Some weariness might be forgiven when viewed through the lens of historical accountability, rather than a purely aesthetic frustration. Certainly the weariness—I would also call it self-consciousness—floating over Wrong Norma can be attributed to both. And this is where things get tricky.

Sontag goes on to describe silence in the arts as a yearning for the ahistorical, the pure, the eternal. Carson’s romance of eternity, of a language out of time, as it were, simultaneously represents Wrong Norma’s greatest weakness and its greatest potential strength. We need only look at a handful of the pieces that deal with manifestly political content.

“Clive Song,” for instance. The brief prose poem narrates breakfast with the eponymous lawyer, who represents clients detained in Guantanamo Bay. Carson’s narrator wonders how this man can worry over the fact that his son isn’t a fan of Monty Python while holding 35 years’ worth of stories from prisoners in Guantanamo or on death row. Their encounter does not end in an epiphany. No “sacred oaks” come whispering through Clive. He walks away “in his saggy-butt pants,” and the narrator remains unchanged, unmoved.

Another prose poem, “Fate, Federal Court, Moon,” recounts the story of Faisal, a Yemeni refugee pleading his case in federal court. This narrator similarly watches the drama unfold, contemplating the fate of the moon, the judge, the lawyers, Faisal’s smile, “what is or is not a political question,” al Shifa, the law. The pervasive, floating self-consciousness returns—one could view it as exculpatory at worst, merely honest at best. Whatever the case may be, the narrator once again loses the thread, baldly admitting to their own ignorance of the political situation at hand and of Faisal himself. Their linguistic maneuvering only yields more unanswerable questions: “Who can say how silvery it was? Where would he go? Sorry?”

At this point we begin to discern a pattern. There are “certain refugees.” Faisal cannot return to Yemen following “the events in question.” What refugees? What events? No one expects poetry to act as reportage, but such willful obfuscations feel like a betrayal of the very real historical wrongs being described, and the conditions that produce those wrongs.

Paradoxically, the more abstract or seemingly distanced the subject, the more precise and scalpel-like Carson’s language becomes. In “Poverty Remix (Sestina)”, for instance, she employs the French verse form to interrogate society’s need for a scapegoat—the poor, the criminal, the diseased, the homeless. Her rage is palpable (“No gloves, here’s a dollar, no hands, out!”), her syntax and imagery shocking (“Tell me, is ‘drive them out’ the same as ‘have stones for eyes’/sung in a shame-resistant extragrammatical grand-nasty mother-fig-fucker/flogged rhythm that soaks the bread/in blood and rips the cloak/off the scaped goat?”). The eight appendices that follow masterfully blend an account of the 6th century BC poet Hipponax with the speaker’s observations on shame, purity, and encountering homeless people on walks to and from the YMCA. Here we find a renewed energy, owed at least in part to the scholarly distance of the form and to the generic nature of the subject matter, generic subjects being the province of myth. By zooming outwards, Carson frees herself to swerve and dive and pinwheel around the subjects that incapacitate the speakers of more narratively straightforward pieces. For another inspired example of this we need only look at the centerpiece of Wrong Norma, “A Lecture on the History of Skywriting.”

First performed at the New York Live Ideas festival in 2016, “Skywriting” finds Carson assuming the persona of the sky itself, who narrates, in Calvino-esque fashion, the creation of the world over the course of a week. It is a candy apple filled with razor blades, and represents in miniature everything Carson does best: We have her trademark wit, replete with references to Greek mythology, Virginia Woolf, John Cage, Yoko Ono, Kant, Proust, and Beckett (a charming interlude takes the form of the sky’s conversation with Godot, whose first name turns out to be—impossibly, perfectly—Rusty). There are interviews with rocks and ruminations on the many varieties of shade. At one point Carson even quotes herself, interpolating a brief section from her 2005 collection Decreation.

Toward the end of “Skywriting,” the reader encounters a block of seemingly untranslated Arabic text. In fact, the following section, Saturday, constitutes the translation, an account of “sky as a medium of annihilation.” Modern aerial warfare has liberated its perpetrators from seeing the human faces of their victims. Without a face, the sky declares, there can be no ethics, no narrative, no communicable reality. Carson’s 2016 performance of the piece reveals that this section was translated by Faisal bin Ali Jaber, presumably the same Faisal of “Fate, Federal Court, Moon,” whose nephew and brother-in-law were killed by a US drone strike (Ali Jaber reads the section aloud in the video). Because Carson offers no citation, the section remains, for the non-Arabic speaker, a block of muteness. The overall effect is profound, a brilliant act of poetic misdirection that dramatizes what is otherwise unspeakable. Rather than resign themself to the role of an unknowing outside observer, the sky utilizes their omniscience to implicate the reader directly, rendering our complicity—and by “our,” I mean the American who reads poetry while their tax dollars fund atrocity after atrocity—unsparing and absolute.

“Skywriting” takes a stand, so to speak. The writer stands in for sky, who stands in for god(ot), who “never gave a fart for” bearing witness to the atrocities of our time. In a god’s absence, the piece seems to be saying, the writer must assume this burden. Every day we are inundated with images of the heap—mangled children, unidentifiable corpses, cities obliterated into rubble and ash. Language recoils from attempts to describe it. Language fails. If there is one duty left to the writer—to any artist using language—it is to make use of this failure to recuperate the meaning of seemingly hollowed out terms like “justice,” “morality,” or “righteousness.”

•

One thing about the heap—it spills, leaks, and contaminates. Pieces about such apparently whimsical subject matter as, say, a forensic scientist who enlists a crow to help them take down a small-town drug lord (“Thret”) or two home invaders thwarted by a snake (“We’ve Only Just Begun”) still bear a trace of its stench. It also makes the weaker pieces in the collection all the more curious and poignant. For the two mornings do exist. The small, stubborn, singular ‘I’ can never fully be dissolved. This is a meaningful contradiction, one Carson identifies herself in an essay on Marguerite Porete in Decreation:

To be a writer is to construct a big, loud, shiny centre of self from which the writing is given voice and any claim to be intent on annihilating this self while still continuing to write and give voice to writing must involve the writer in some important acts of subterfuge or contradiction.

In other words, the writer must embody “a presence (dirt) solved by its own absence.” What might such an attempt look like? Wrong Norma offers us with several options. Deviance from received forms, for one. Incompleteness. Fragmentation. An emphasis on process, in which the promise of an imagined “finished” work extends past the boundaries of the page to some other, mysterious place. Sontag again: “If written language is singled out as the culprit, what will be sought is not so much the reduction as the metamorphosis of language into something looser, more intuitive, less organized and inflected, nonlinear (in McLuhan’s terminology) and noticeably more verbose.”

Also, resignation. The issue posed by an intrusion of the political is inherent in the very notion of politics itself, which concerns the nature of our imbrication with the lives of others. The self cannot step away; it must be accountable to its own capacities and limits. Carson works over this blunt fact time and time again throughout Wrong Norma, to varying degrees of success. Hence the frequent use of rhetorical questions, invocations of purity and shame, anxieties about the limits of language. I am thinking of a line from the stream-of-consciousness title piece, the very last in the collection: “I drift to the past, even 20 years ago wasn’t it possible to be pure? To just close the door and think about one thing, the moon, curbs, Etruria. The self wins anyway.”

Twenty years ago, perhaps, there would have been an answer. Now the moon is also the sky is also the “death-bringing stuff” flying through it and the human wreckage left in its wake. But hasn’t this always been the case? a more cynical reader may interject. What’s taken her so long? Carson would be the first to agree. Here she is on feminism, from her 2004 Paris Review interview:

I think that for a long time, I was just a solipsist. It’s not really that I was not a feminist, or didn’t understand feminism—I didn’t understand masculinism either—but that I just didn’t understand being human. And it’s a problem of extended adolescence: You don’t know how to be yourself as a part of a category, so you just have to be yourself as a completely strange individual and fight off any attempt others make to define you.

Carson’s project of extended adolescence—her rejection of imposed categories—persists, for better or worse. We should be thankful for it. Even if the speakers of Wrong Norma occasionally flirt with despair, the collection as a whole does not resign itself. It is a restless, searching work, the latest attempt in a lifelong quest to find language that can express the ineffable, only the domain of that ineffability has extended beyond the realm of singular personal experience. Take the strange piece titled “Todtnauberg” nestled toward the end of the collection. It depicts the infamous 1966 meeting of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger and the Romanian-Jewish poet Paul Celan at Heidegger’s mountain hut. Heidegger was an avowed Nazi from 1933 until the end of the war. Celan, whose parents both died in a concentration camp, left strikingly little record of their encounter, save for his name in Heidegger’s guestbook and the titular poem, which Heidegger apparently loved.

Like the best pieces in Wrong Norma, “Todtnauberg” is most thrilling in the gaps where thinking takes place. The first page summarizes the bare facts of the meeting, including Celan’s death four years later by suicide. In the pages that follow, we get Carson’s own drawings of Heidegger shamelessly whistling; his shadowed hut, or “hütte”; the ghostly branches of a tree (death waiting for Celan “dressed and ready”); the mountain at night. The drawings—messy, rough-edged, cut-and-pasted into squares, like tiny windows—remain simultaneously evocative and unyielding. Whatever answers are to be found lie in the blank space around them, that looming, claustrophobic blankness. Snow. Shame. History. Monstrosity. The steaming, stinking heap of it. Carson lets it answer for itself.