The Art of Noticing: On Alison Townsend's "The Green Hour"

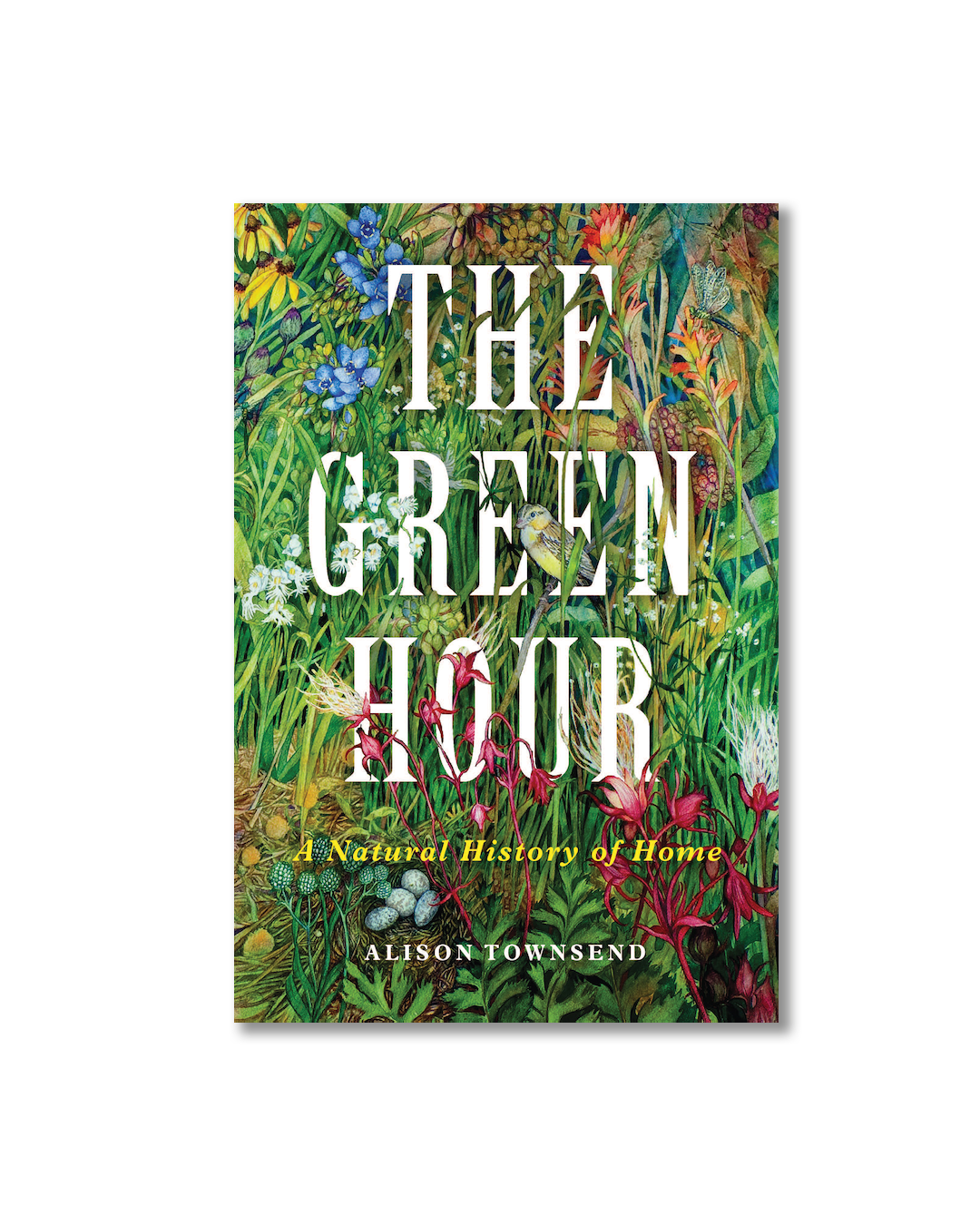

Alison Townsend | The Green Hour: A Natural History of Home | University of Wisconsin Press | 2022 | 256 Pages

The first time I saw an image of William Sommer’s “Winter Landscape” painting, I was doing something unmemorable online; but I remembered the moment I saw it perhaps even more than I remembered the painting itself because it so strongly evoked the view from my childhood bedroom window. The colors of the snow clinging to muddy fields, the barns in the distance so transporting they could have been a madeleine crumbling in Proust’s tea. I had fallen through thirty years, and I was immediately back at that bedroom window, in the house that my father had built, gazing out at a landscape I hadn’t seen in years.

Why do familiar landscapes affect us so? How do they remain a part of us no matter how many years pass? In her new book, The Green Hour: A Natural History of Home, Alison Townsend answers these questions by rendering the feeling of time’s passing in lyrical, lovely prose.

Townsend grew up in eastern Pennsylvania, but collected landscapes over the course of her life: southern California where she met her first husband, western Oregon, and Wisconsin, where she met her second husband and currently resides. Her mother, a trained zoologist and artist who died of breast cancer when the author was only nine, taught her how to appreciate nature and to notice the subtleties of the world. After her mother died, nature became a retreat. Townsend’s father, a chemist with three young children, remarried quickly, creating a blended family of five children with parents who didn’t really get along. The kids sought refuge in the woods, sleeping out next to the stream called Day Lily that ran through their property and served as backdrop to her turbulent teenage years. For Townsend, landscape has the power to humble and soothe. She writes:

In the morning we woke, cranky and stiff, the magic of our night in the Pine Forest countered by the reality of having to return to the pain and confusion in our lives. Still, we were filled with the sense of having gone somewhere special. Trooping back down the hill, we were quieter than usual, holding the sound of the stream and wind in the pines inside us, careful not to spill a drop.

The Green Hour—titled after the way the light falls on late spring evenings across her home in Wisconsin—is a lush, beautiful collection of personal essays that span Townsend’s life and reflect on the mysterious ways landscape imprints on us and makes us who we are. Her essays, each one uniquely structured, reflect a curious and poetic mind, and it is clear that she’s spent her years seeking out nature and paying attention to the world around her. The pieces cohere into a memoir told with a loose attachment to chronology, looping through time and memories, building into a lovely piece of art. But the book is not only about natural history and home, it’s also about grief, marriage, and the nature of time’s passing. Townsend uses images of flowers, her mother’s dress, landscapes to travel through time, linking her present with her past. In doing so she has created a map of a life that spans the country.

Early on in the book, Townsend introduces the lake near her home in Wisconsin, and writes about memory and slipping through time: “I am amazed and grateful at how the past, present, and future sometimes occur simultaneously, woven into that continuum Native Americans call ‘ceremonial time.’ This is the way memory works, too—our lives like drops of rain fallen into the long history contained in the lake left by a glacier.” In college, Townsend and a friend spent a summer living by a pond Thoreau-style. They stayed in a rustic cabin that used to house summer campers and rowed a boat to get to work every day. They read by the light of a Coleman kerosene lantern and bathed in the pond. When summer came to an end, Townsend emerged from the experience leaner and stronger, free of the heartbreak that had weighed on her when she arrived. When she returns years later, the cabin is gone but the pond is still there, as are its pull and power over her.

Townsend, who has published several books of poems, prefers poetry to scientific information (though she includes that too), describing the landscape in both broad strokes and intimate detail, rather than telling us how it works. She writes about her habit of planting the same flowers:

The violets in my backyard here connect me to the pansies I have planted in the front of the house, which in turn link me back through every year I’ve ever planted them. They remind me that we love flowers not just for their physical beauty, but for the way they anchor us in our lives, accompanying us through time that stretches beyond our personal history into a past that unfolded long before us, even as we bend to plant this year’s flat, the purple and yellow faces splotched with black looking up at us as if they know all this and more.

The true pleasure of reading a book about landscape and the passage of time is spending those hours in the author’s company, and Townsend’s company is wonderful. She is a poet who is well-read and has paid attention; she is the kind of person who takes a minute to fall into the pile of leaves she’s just raked and lay there for a while, watching; she marvels at the world, finds her solace there, and has painted it for us with words.

Landscapes imprint on us whether we know it or not, especially those from childhood. Townsend has a stunning ability to make landscape personal, drawing connections through time and geography and evoking all the feelings that a place, or even the image of it, holds within us.