The Secret City: Aaron Lange on the 1970s Cleveland Punk Scene

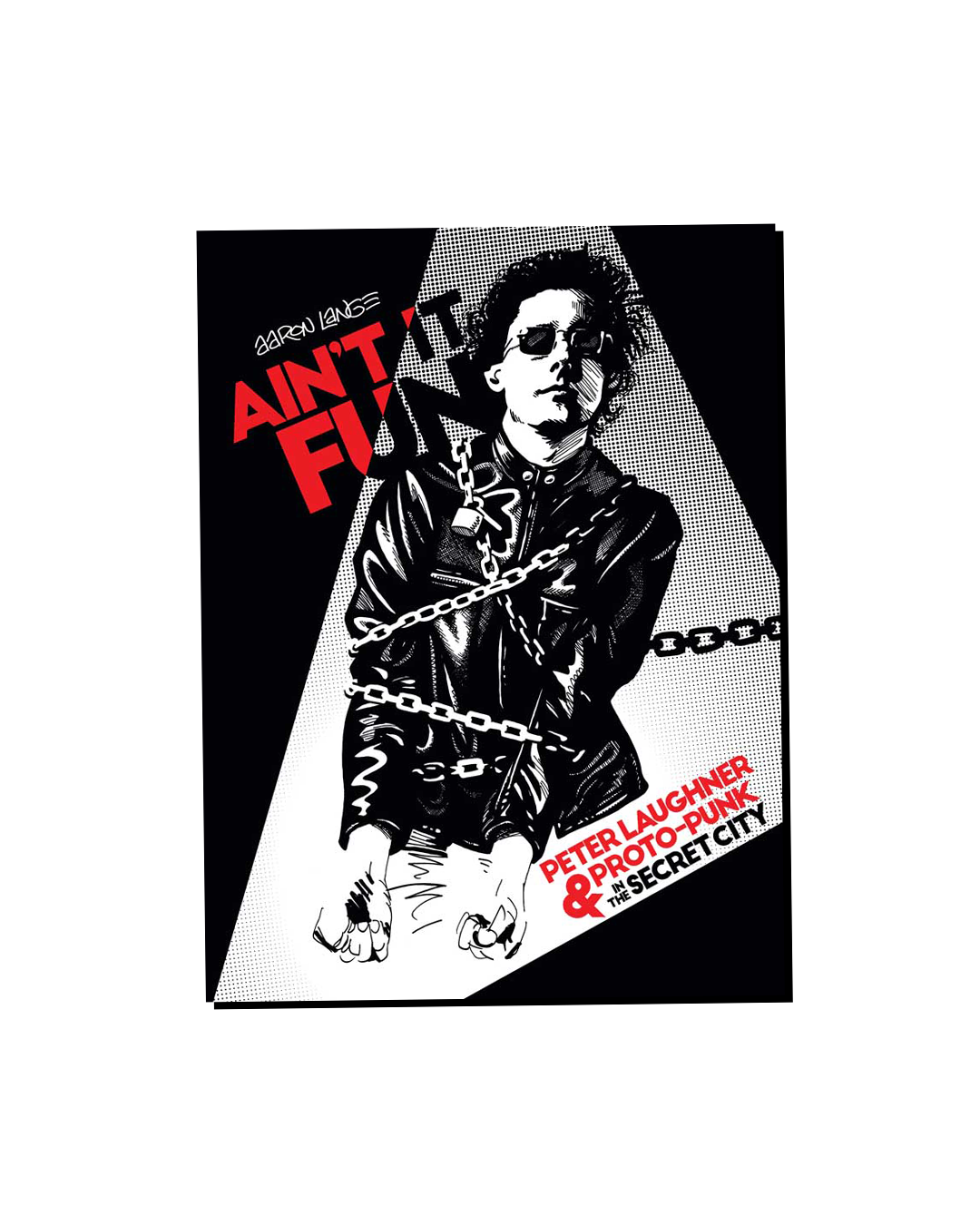

Aaron Lange | Ain’t It Fun | Stone Church Press | October 2023 | 448 Pages

Many people know the origin stories of punk rock in London and punk rock in New York City, but fewer people know the history of punk rock in Cleveland. Aaron Lange’s graphic history book, AIN’T IT FUN: Peter Laughner and Proto-Punk in the Secret City, reveals the centrality of this rust belt city in the formation of punk rock culture, along with many detours through other subcultures, violence, and class struggle. It centers on Peter Laughner, the guitarist in Rocket From the Tombs and Pere Ubu, while exploring the tensions that exist in the Cuyahoga River Valley where Cleveland was made, right at the northern tip before the river becomes Lake Erie.

Lange’s book was a no-brainer for my summer reading list this year— as a native of Akron, 40 miles down the road from Cleveland, and an avid listener of punk since adolescence, I read it right before taking a family trip to see my parents. One day, my wife and I left our baby son at home with the grandparents and went to the top of the Terminal Tower in downtown Cleveland. The tower was the highest tower in the United States – outside of New York City – until 1964, which is the same year the Cleveland Browns won their last NFL championship, thirty-two years before the original team would leave Cleveland for good. If it sounds like I am framing my narrative in the sense of what was past, that’s because I am. As we looked out at Lake Erie and the cityscape, my wife remarked that Cleveland has a lot of “promise.” While such a word usually connotes a positive meaning, in this case, knowing the history of the area, I interpreted it as “lacking.” Maybe it’s because I spent my youth hearing about how industry had left (my family had worked for Goodyear, as had many people in previous generations in the Akron area) and of course the Browns had left and Lebron had left and different punk bands–documented in Lange’s book–had left and the Black Keys had left and so on.

But Lange’s book, published by his hometown Stone Church press, made me realize the lacking wasn’t quite as profound as I’d thought. Here is Lange, born in Cleveland, showing the scope of the area from pre-Europeans to present, always pulsing, always violent. And, importantly, Lange is doing this in the present. Lange’s book puts in perspective for me that all that leaving – and the book’s core still does emphasize the postindustrial turn of the 60s and 70s when productive capital did literally start to leave – was just one part of the city’s long arch, just one movement in the awesome historical ebb and flow in which I’ve luckily gotten to swim along for a bit. In fact, Cleveland was central in the 70s punk explosion.

It is hard to classify the book; in an interview on the TrueAnon podcast, Lange said he just called it “graphic novel” as a surrender to its unclassifiable, genre-fusing approach. Black-and-white artwork on slick pages, dart from historical points to geographical points with cultural and social anecdotes sprinkled throughout, all gradually weaving together into a tapestry of the greater Cleveland area as we now know it. Set in the wider historical context from the land’s indigenous tribes and settler colonialism to robber barons like Rockefeller then to Cleveland’s late 20th century decay, Lange presents a beautiful and moving depiction of Laughner as a tragic poet amidst the end of the industrial empire of which Cleveland and Northeast Ohio were a microcosm. We see the Velvet Underground, who had a residency in Cleveland in the late 60s and inspired the punks that followed in the 70s. We see the 1970 Kent State shootings, where the band that would become Devo was born. We see the Dead Boys, formed out of the ashes of Rocket From the Tombs, while other members of that band formed Pere Ubu.

Most importantly, Lange gives us a panoramic view of a place that is constantly in struggle. The struggle is over land, materials, status, lust, love, obsessions, dreams, art, and more. At over 400 pages, it’s worth the $39.99 price of admission. After reading, I was impressed, but also had questions, so I hit up Lange and we spoke about the book, his craft, punk, Cleveland, and his literary imprint Stone Church Press. Our conversation is below.

Andrew Worthington: How did you come about the idea to write a graphic history on Peter Laughner and Cleveland?

Aaron Lang: I discovered Pere Ubu late in high school; I heard “Final Solution” on a compilation CD that Rhino released—this was the late 90s— and was really impressed by it, I’d just never heard anything like it before. Then while looking at the liner notes, I learned they were from Cleveland, which was unexpected. Growing up in Cleveland’s suburban west side, it didn’t seem like anything interesting ever happened here. It seemed like all art or culture came from NYC or London. So that made an impression, though it would be years before I had any idea who Peter Laughner was. Then in the early 2000s, when I was an art student in Columbus, Rocket From The Tombs got back together and I saw them perform. Around that time, I started to occasionally hear things from friends about Mirrors and electric eels, and I was always really curious about that old scene. It seemed so obscure and shrouded in mystery. As the years went on I’ve always kept that interest in the back of mind, and when possible I would add to my collection of Cleveland records. Eventually it became a dominating interest, and Peter Laughner stood out to me, as a personality and as someone who seemed to embody that entire zeitgeist.

AW: Although Peter grew up well over a century after Ohio was settled, there is a violent stench that hangs over everything—serial killers, riots, and suicide. How intentional was your choice to portray the histories you did in the book? In a sense, was Peter's suicide an attempt to overcome that violence?

AL: Pere Ubu and company referred to themselves as “urban pioneers,” and Devo referred to themselves as “pioneers that got scalped.” It seemed only natural to start the story early with the settling of the area. The pioneer and frontier and wild west myths still run very deep in this country. The gangster archetype was a continuation of that, and Peter was very attracted to that romantic vision of outlaws. With some exceptions, he wasn’t a violent person, but he did glamorize violence, especially in regards to guns. And just to be clear, Peter did not technically commit suicide, but rather destroyed himself slowly. His behavior may have been suicidal, but he never made a firm decision to end his life. On the contrary, shortly before dying he had been making plans and thinking about his future.

As far as some of the other historical depictions of violence, I believe that certain events leave an imprint on the psychic landscape. Not just violence— things that are ecstatic or just plain weird can also leave their mark, and I think I addressed examples of all those things in the book. In the case of the Torso Killer, he operated in the industrial valley of the Flats, an area which later played an important role in the punk scene that developed here. So that was a good way to introduce the area. Secondly, Eliot Ness was involved with the Torso case, and Ness ties into some of what I was just saying about Americans and their vision of themselves, re: the wild west, outlaws, etc. Ness’s real life was fairly distinct from the “Untouchables” legend that formed after his death, and that’s an idea that informs a lot of the book—how certain events or people enter a folklore and live on as archetypes. Given Peter Laughner’s early death and how obscure much of his recorded output was for a long time, I think Peter also somewhat entered the realm of folk legend.

AW: How do you think Laughner would perceive and interact with the music world of today? Or even circa 1980?

AL: I have no idea how Peter would feel about things today, but I do think he would have been energized by what happened between 1978 and the early 80s. I think the various strands of post-punk, including goth, death rock, and industrial would have interested him greatly.

AW: The proto punk scene of the Cuyahoga River Valley represented a rebellion against middle class stasis in postindustrial society. If you had to define the values of that rebellion, what were they? I ask because much of the book is focused on Laughner and therefore the rebellion seems unorganized, amorphous, and possibly even ineffable.

AL: Yeah, I don’t think there was any particular ideology, and in the case of the electric eels it was just pure nihilism. I think Peter was just specifically opposed to the stifling conformity of his post-war suburban childhood, and just an all-around champion of creativity and personal freedom. As far as I know, the most concrete manifestation of this outlook was his early championing of gay rights, which was not a common thing for his time and place. Peter deserves credit for that.

AW: While the people you focus on most in the book come from a highly political landscape, the politics of a lot of the Cleveland protopunks is hard to discern, especially with Laughner. While Devo is clearly politicized in obvious ways, groups like RFTT, Dead Boys, and Pere Ubu have less clearly defined or pronounced politics. Am I misreading this or would you say there is an apathy that infected young artists in the 70s, especially in Northeast Ohio? Curious what you think.

AL: Devo was definitely political, or at least born from politics. And as I just mentioned, the eels were nihilists. The Dead Boys had zero politics. As far as the Ubu crowd, it’s tempting to try and insert some sort of political reading, but there just isn’t enough there. I think it’s safe to assume though that they were all vaguely leftist, in that late counterculture kind of way, which was a bit jaded. But nobody in the Cleveland scene was expressly political in the way that certain English bands were. There is certainly a labor history here, and a Socialist-infused scene is not hard to imagine, save for the fact that much of the early CLE scene was middle-class and suburban.

AW: I’ve often thought about the difference between the Akron and Cleveland punk scenes during this time. Cleveland is grittier and more anticipatory of punk and post punk while Akron seems a bit more artsy and anticipatory of new wave and electronic music. If there is such a dichotomy, how could one explain it?

AL: There was definitely a difference between the Akron and Cleveland scenes, and I think you are right about Akron leaning more in the new wave direction. But I wouldn’t say Akron was more artsy, as Pere Ubu was hands down the most artsy group to come out of Northeast Ohio. It’s a vague description, but I think the Akron scene could be described as more “collegiate”—with Akron groups like Tin Huey, you get the sense of college kids being a bit goofy and just having a good time. That might sound like I’m belittling Huey, and I don’t mean too. They were drawing on experimental and Kraut rock influences just like Ubu were, but while Ubu could seem aloof, Huey (and Devo) weren’t afraid to look like they were having fun.

AW: Cleveland Undercovers by da levy is explicitly mentioned but also seems to be a stylistic inspiration, especially in the final stretches of parts 1 and 3, where the text seemingly speeds through a litany of allusions to different Cleveland events and people. The book seems rambling and precise at the same time. How did you go about writing it? What was your process? Do you do the words and the art together or one before the other?

AL: The early drafts were definitely more rambling, but I do like to think that the finished book has some degree of precision. I didn’t know what I was doing at first, and I basically ended up throwing out the first 100 pages and doing them over, and that’s in addition to all the other editing I did. I started out by writing chunks as a script. I’d draw those chunks, then write and draw another chunk— like maybe 10 to 20 pages. That way of working helped me get going without feeling overwhelmed, but after a while I started to realize that it felt disjointed. So I fixed all the early pages, wrote a complete script for Part 2, and a detailed outline for Part 3 (with the intention of fully writing that part after all other pages were illustrated). My “scripts” would be total gibberish to anyone else trying to decipher them. When appropriate, I’ll make notes to myself on what the illustrations will be. But the script is not written in stone, and when it is time to draw the page, I’ll often change things. I imagine it’s a bit like a movie, where the screenplay is fine on paper, but once you get rolling something feels off, so you let the actors improvise and let things happen organically. As far as da levy, I do think he was an influence in the writing and construction, at least in some subconscious way.

AW: How did you get interested in art and literature? How did growing up in NEO specifically influence you as a creative person?

AL: I was always interested in art, and always like to read. As a boy, comic books and science fiction were driving passions, and then in my teens and early 20s I went through that whole beat phase. But I don’t get stuck in ruts, and I don’t like to endlessly revisit the interests of my youth. I’m always looking out for new things and flitting from one new obsession to another.

As far as Northeast Ohio’s influence on me? I imagine the psychosphere here informed me in a broadly similar way to how Laughner, d.a. levy, Harvey Pekar, etc. experienced it. And that’s all in the book.

AW: Talk to me about Stone Church Press. How did it originate, how has it developed, and what are the goals of the press?

AL: I started SCP with Jake Kelly, another Cleveland artist, who has been working on a wide-ranging series under the banner DEATH, DESTRUCTION, VICE, & SLEAZE. In the most reductive sense, he’s doing true crime as it relates to Cleveland’s history, but it’s not like serial killer stuff, it’s more about social currents and political violence. His next installment, HARDHAT WEATHER, deals a lot with the Weather Underground’s history in the area, and from what I’ve seen so far it might be his best work yet. That should be available in 2025.

As far as our plans for the press, in addition to our own work, Jake and I want to publish things that interest us— projects that might not have happened otherwise if not for our involvement. There’s something gratifying about putting out a book and knowing that nobody else would have been crazy or stupid enough to do it. Mainstream publishing has grown very timid and bland, and in response there has been a surge in interesting small presses doing exciting things. I don’t mind saying that we are a part of that trend.

AW: What works-in-progress projects are you working on?

AL: As I mentioned, Jake’s new book should be out next year, and we’ll also be doing new printings/editions of his earlier installments from the same series. More immediately, as I write this we have two books at the printer right now, which should be available in October of this year. One is by myself, and it’s called PEPPERMINT WEREWOLF: MURKSTAVE. It’s a bit of a vanity project, much more esoteric and abstract than AIN’T IT FUN. It’s hard to summarize, but it deals with sacred geometry and Germanic runes, but through a pornographic lens. How’s that for an elevator pitch? The other book, which I had the pleasure of editing, is a collection of drawings and poetry by John Morton of the electric eels. John is very creative outside of music, and this is the first-ever publication collecting his work. It’s exactly the kind of thing that Stone Church Press was created for, and we’re excited to let it loose out into the world.