A Very Thin Atmosphere: On Hannah Brooks-Motl’s Earth

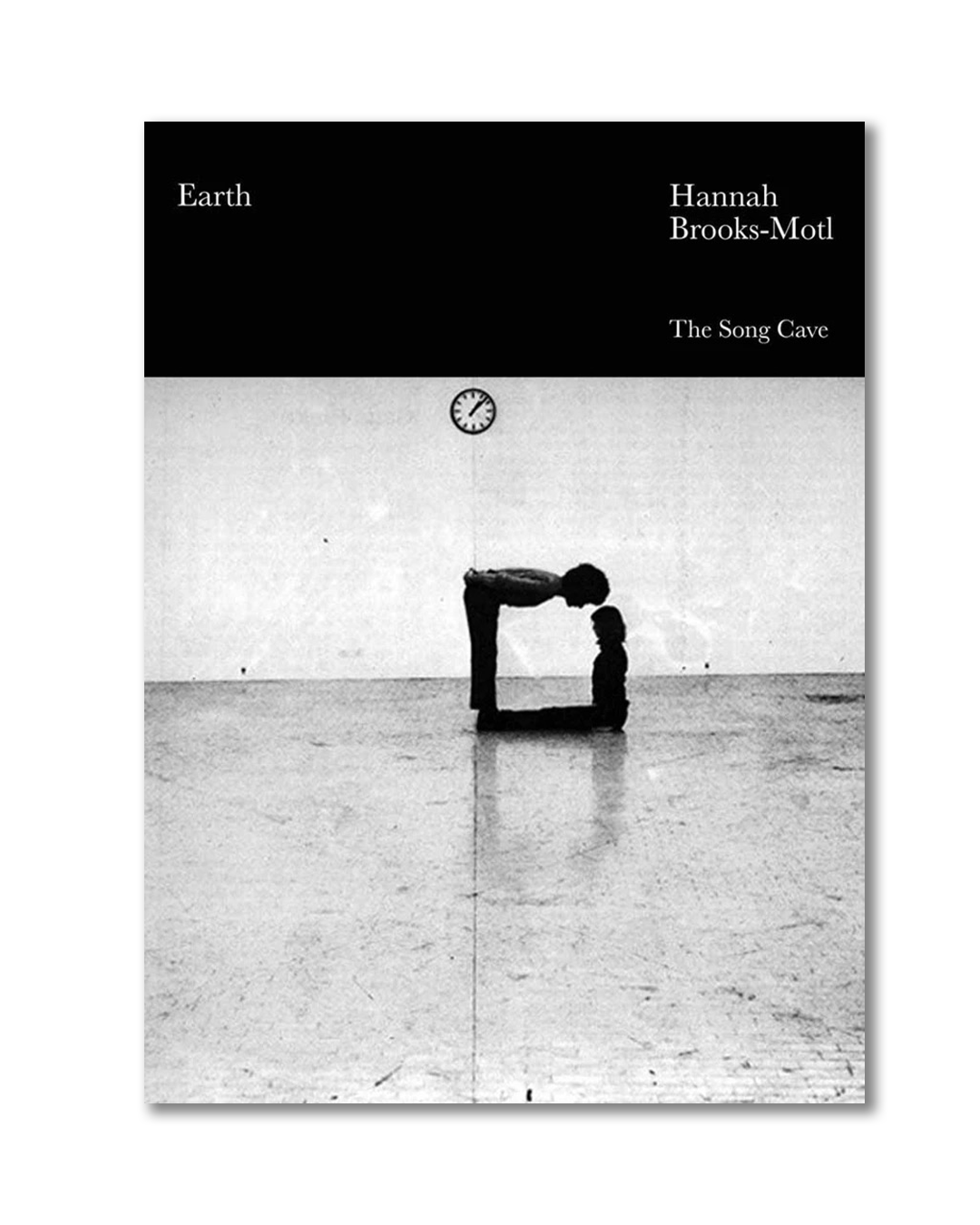

Hanna Brooks-Motl | Earth | The Song Cave | 2020 | 95 Pages

Perhaps, the problems of the moment are harder to bear because of phrases like “the problems of the moment” (see: “now more than ever,” “in these complicated times,” etc.). Such phrases cover one’s rhetorical ass, while saddling it with ambient baggage: they seem inclusive, but they evade particulars. The answer, proponents of elemental style might say, should be exactitude, rigor of thought and expression. But my mouth and the words keep changing. So does the situation I’m speaking into. I could figure things out, but by then things will be different. What will public education look like in three months? How’s my family? Do we have to have a president? Hannah Brooks-Motl’s latest collection of poetry, Earth (The Song Cave, 2020), speaks from an interregnum in which the language we have isn’t enough (“all theories of life / now breached”), and yet it’s the language that composes us. She shows the struggle for meaningful speech, which can reroute through close looking, as in this passage from “Living,” the book’s first poem:

People struggled through the ratio—

what do you remember about it?

It was a garland of lilies stitched into fabric.

There was a spirit named Impudence

to fall in love with. There were three potheads

out in the dark; a curtain tacked up as a door.

That final image has the structure of an epiphany—of a conclusion bursting from the jack-in-the-box of the poem—but it doesn’t neutralize the poem into a resolution. Rather, the closing phrase emphasizes materials, not meaning (“I had zero / ideas,” Brooks-Motl reports). This approach to imagism is tinged with allegory, or iconography, thanks both to the appearance of Impudence, that heart throb, and the bas-relief of those stoners. Throughout Earth, Brooks-Motl (who I’ve known personally since 2008) offers “little universals / But no synthesis.” This emphasizes the “local meaning” and sculptural reality of matter that ranges from the “ruffled tops / of window drapes” to a “blanket / printed w/boobs,” from a “broken orange” to a “toddler // arranged fetchingly / around the drip // candles.” In “Parable,” Brooks-Motl presents the self as a similar bricolage of “one’s cat, one’s routines, // a dullsville books, some tea.” Elsewhere, daily actions become a choreographic assemblage:

tried to get on my mitten glove combination

pushed my thumb through.

enjoyed the bad pop music

changed radio channel 4-7 times,

drove around. combed hair with hand, waited

scraped gunk from mouth corner, moved my toes

The transcription continues but grows more abstracted:

rotated feet poorly in boots, “squared” shoulders

curved fingers around opposing textures.

pushed thumb down to erase attention.

lifting chin through recent changes.

The quotes around “squared,” the generality of “textures,” the motivation to “erase attention,” the vagueness of “recent changes,” the quality of clipping in “rotated feet poorly in boots”—these point to how Earth complements its material precision with expressive smears. This kind of dissolve is similar to the wonder and ambivalence of the book’s title, which suggests, to my reading, both vastness and anticlimax, since any nature poem, any poem, anything on earth could be titled “Earth.” It also recalls the “parallel shine” that Brooks-Motl says can exist alongside “one’s conscience.” By diminishing the precision of analytical conscience, at times, and favoring that “parallel shine,” Brooks-Motl showcases “heaps of stuff” and “basic shit” and “extravagant shit” and “the New American anything.” These are phrases of a “bold stroke in blunt language.” They evoke a condition in which any “experience,” however significant, may be a mere “occurrence.” In response to the “decay of the robust / historical imagination,” she suggests that “thin states predominate”:

it’s coming from that clump of trees,

a busy irresponsible afternoon. could you tear

the socket between us reinstall

lie back let my joints open.

walked quietly it was 6:30-7:15.

I think it’s a very thin atmosphere,

the freedom of art

not fragile but thin.

In philosophy, “thin concepts” describe but don’t evaluate, or else they describe vaguely, depending on who’s philosophizing; “heaps of stuff” is a thin concept. In Brooks-Motl’s poems, the world may be “thick but uncertain,” and so emphasizing a “very thin atmosphere” can be a way of making room by “doing away // with the parts that are most.” The results may reflect “giving everyone space as an ideology,” or how “a blanket / over the windows” of a house can suggest, through its obstruction, “pure possibility.”

The extended passages above are from the book’s longest poem, “Virtue Theory.” It considers how “to inhabit / a moral philosophy w out being annoying about it.” Its engagements with landscape, family, the ballad tradition, and more are luscious, stark, rapt, fractured, and durably aphoristic. It’s heady like hard thinking, and like a low-pressure front. Perhaps, it suggests an ethics of conceptual thinness. By foregrounding perception, not perfectly integrated information, one can slouch and shrug into more supple relation. These moments also account for loss, because they emphasize a “very thin atmosphere” and its gaps, rather than the disingenuous specificity of phrases like “now more than ever.” Such acknowledgment makes room for the hope, as Brooks-Motl writes, that “it will all flash recognizably again.” This ethics of conceptual thinness, this artifice of parallel shine—they show that the mundane is active, too:

lazy cycle, wear it down.

disappear

into a little skit

called human artifice.

action in our common life,

action in bed. that’s fine.

There’s resignation and realization and appreciation in this fineness. It reminds me of George Oppen’s invocation of days that have “only the force / Of days // Most simple / Most difficult.” Now more than ever, in these complicated times, the pandemic makes it easy to feel the strain of both simple and difficult days, of both excess and lack. The news is too much, and I’m killing time at home. Catastrophe is acute, and I’m working a jigsaw puzzle. Experience is restricted; experience is intensified. Brooks-Motl’s previous collections, The New Years (Rescue Press, 2014) and M (The Song Cave, 2015), established her as a poet of spectacular insight, formal dexterity, and lucid sensory textures; her work often charts the meeting of the momentary and the momentous. And so it’s affecting that “at moments,” as Jonathan Suhr wrote in The Adroit Journal, “Earth reads like a postmortem to language.” Perhaps that postmortem is similar to the “reckoning” that Brooks-Motl suggested we’re in the midst of, in an interview with Emily Hunt shortly before the pandemic hit. “The ways we’ve organized ourselves and thought we knew how to live no longer hold,” Brooks-Motl said. She suggested that we need “new philosophies, new forms, new poetries” to help us “adjust to the now.” Earth offers that.