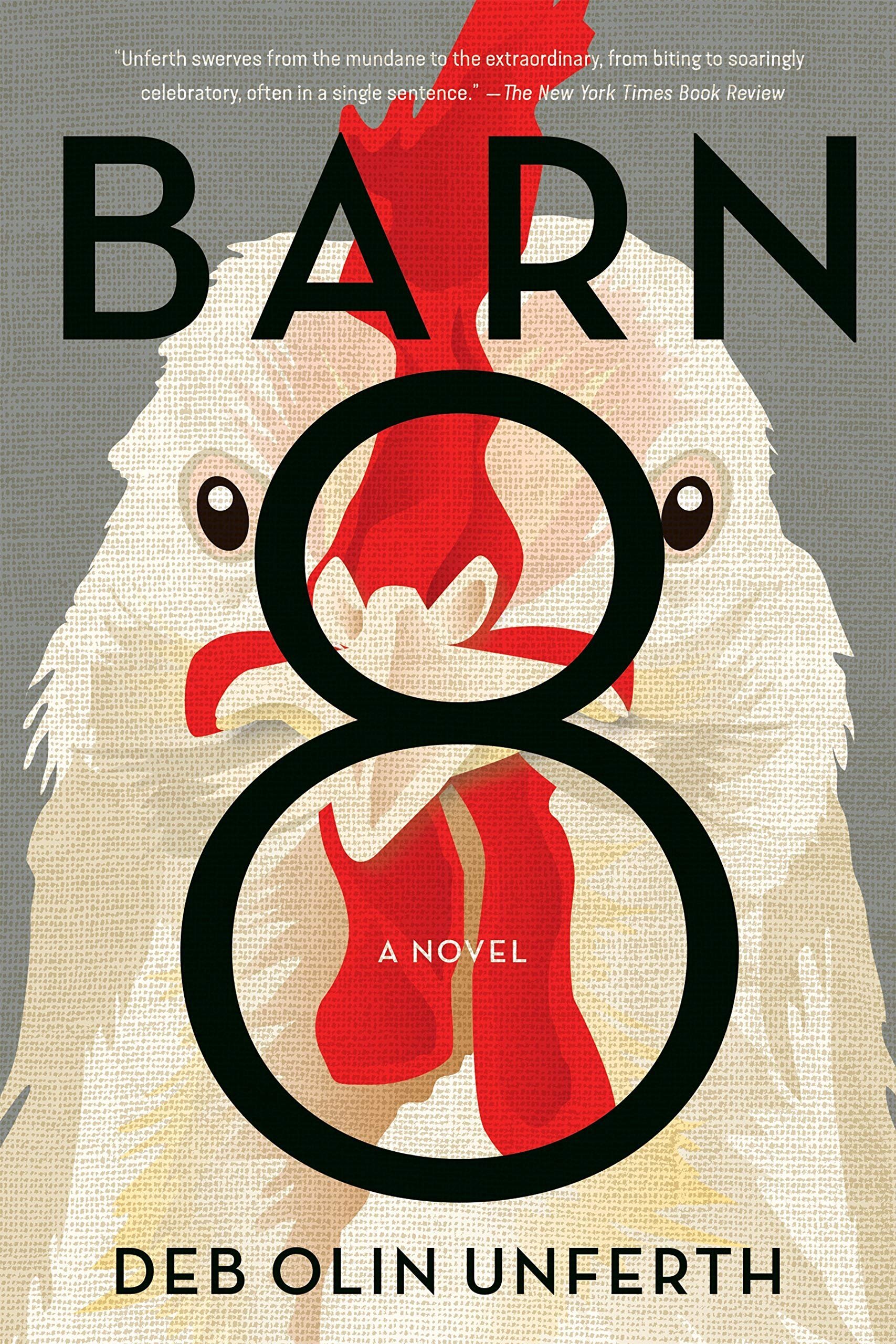

Birds of a Feather: On Deb Olin Unferth’s "Barn 8"

Deb Olin Unferth | Barn 8 | Graywolf Press | March 2020 | 296 Pages

Writing about chickens is new for Deb Olin Unferth. Writing wild fictional exploits is old hat. In this, her second novel and sixth book, the steadily rising, impressively credentialed author stares a massive foe in the face and works tirelessly—wit and incisive writing her only weapons—to vanquish it. This foe is a character of the story as much as any other: corporate egg farming. Her dedication to the topic is more than apparent, and her research speaks for itself. Here is an author so committed to her story that she spent hours in coops, listening to chickens, and giving them human voices.

The focus may be chickens, but the story begins, at first, with humans. Janey is a disillusioned teen at the starting point of a race toward a different version of herself, a “new Janey” whose first mistake begins where the book does. She’s on a bus, leaving her mother in New York to meet the father she’d believed for fifteen years was nothing more than a sperm donor (and certainly not an agricultural worker in rural Iowa). Her mistake is thrown into sharp clarity in three steps: off the bus, into her father’s home, and perhaps most of all, into the reality that the slobby, sullen man in front of her never wanted to meet her. When her chance to return to old Janey is lost, she has no choice but to carry on in the shoes of new Janey. From here, the two Janeys are split in Sliding Doors fashion; two separate lives, the old assumed to be endlessly better than the one she is left with.

The story then turns to Cleveland, a frustratingly dedicated auditor for the US egg industry whose childhood babysitter and lifelong unintended role model was Janey’s mother. Cleveland is the catalyst of the story after one hasty decision (take one chicken from Happy Green Family Farm) spirals out of her control (take more chickens from every nearby farm). When Janey and Cleveland collide, the result resembles a rural Iowan version of Ocean’s Eleven (with fewer geniuses and more vegans). Steal one million chickens--all of them, in fact--from the farm that started it all.

As things progress and move deeper into out of control territory, the focus slides away from Janey and Cleveland and onto an ever-growing, perhaps overly large collection of side characters. Annabelle (the farm’s estranged activist daughter and the new leader of the cause), her ex-husband Jonathan, and her former investigator partner, Dill are their “crack team.” Occasionally, the list of perspectives also includes the original stolen chicken, given a name—Bwwaauk—and an identity, as all Unferth’s chickens would likely receive if there were space and time to spare. The anthropomorphizing of one specific chicken is at first comical and quaint, but eventually feels somewhat unnecessary to those who prefer their narrators to be human and their character lists to be short.

At times, Unferth’s reliance of prophesying can feel heavy-handed, even for a book with animal rights and activism at its core. We expect to feel some of the tragedy of animal cruelty, or a certain level of guilt (or justification) for our own eating habits. Vegans, after all, are both the heroes and demise of the scheme here. The heist crew is made up of highly flawed but good-hearted animal activists, undercover farm investigators, and morally righteous hen warriors. But when the book dips into bleak, end-of-humanity prophecies, we’re sucked a bit too far away from the hens and farm at the heart of the story.

The trick of Unferth’s writing is the sly, almost deceptive nature of it. Portions of text are segmented into bite-size pieces illuminating the goings-on of various characters, an effective device for moving the plot forward while conveying the frenetic and chaotic energy of the characters and the story. You feel jostled about. This is intentional. You are drawn in by a keen feeling of levity, a world of humor surrounding the antics of a chicken-thieving egg auditor and her painfully uncoordinated team. You are hooked by the larger-than-life heist just in time to be caught off guard by the gravity of the facts Unferth laces in. You will learn things in these pages, things you may wish you didn’t know. And that is absolutely the point.

The language of Barn 8 is riveting and masterful. Seemingly opposed phrases are paired together in unique and telling ways: farmers are endangered species and hens are “sweet little puffs” simultaneously writhing in “hot-iron guillotines.” Lists are common fare and always begin rationally (we put eggs in our meals, batters, and sandwiches) and swerve deeply into the figurative (we build rockets to shoot yolks into the cosmos). Even pages dense with facts of chickens and eggs and the farms that tend to them feel right at home. You think, of course I needed to know this. Unferth’s impressive writing at play once again.

Your enjoyment of this book builds exponentially, the more willing you are to give up your grip on reality. While the story is nowhere near fantastical, plenty of elements are far-fetched, to speak lightly. This includes the essential premise itself; stealing a million hens without arousing suspicions seems an impossible task (though the book does admit as much). Other small elements and plot points also require a leniency for their whimsical defiance of reality. But if you’re willing to accept just a bit of fantasy, the payout is a stunning, stark, and twisted tale that defies the borders of what a heist book or a farm book or even a novel can be.