Four Dead in Ohio: On Derf Backderf’s “Kent State”

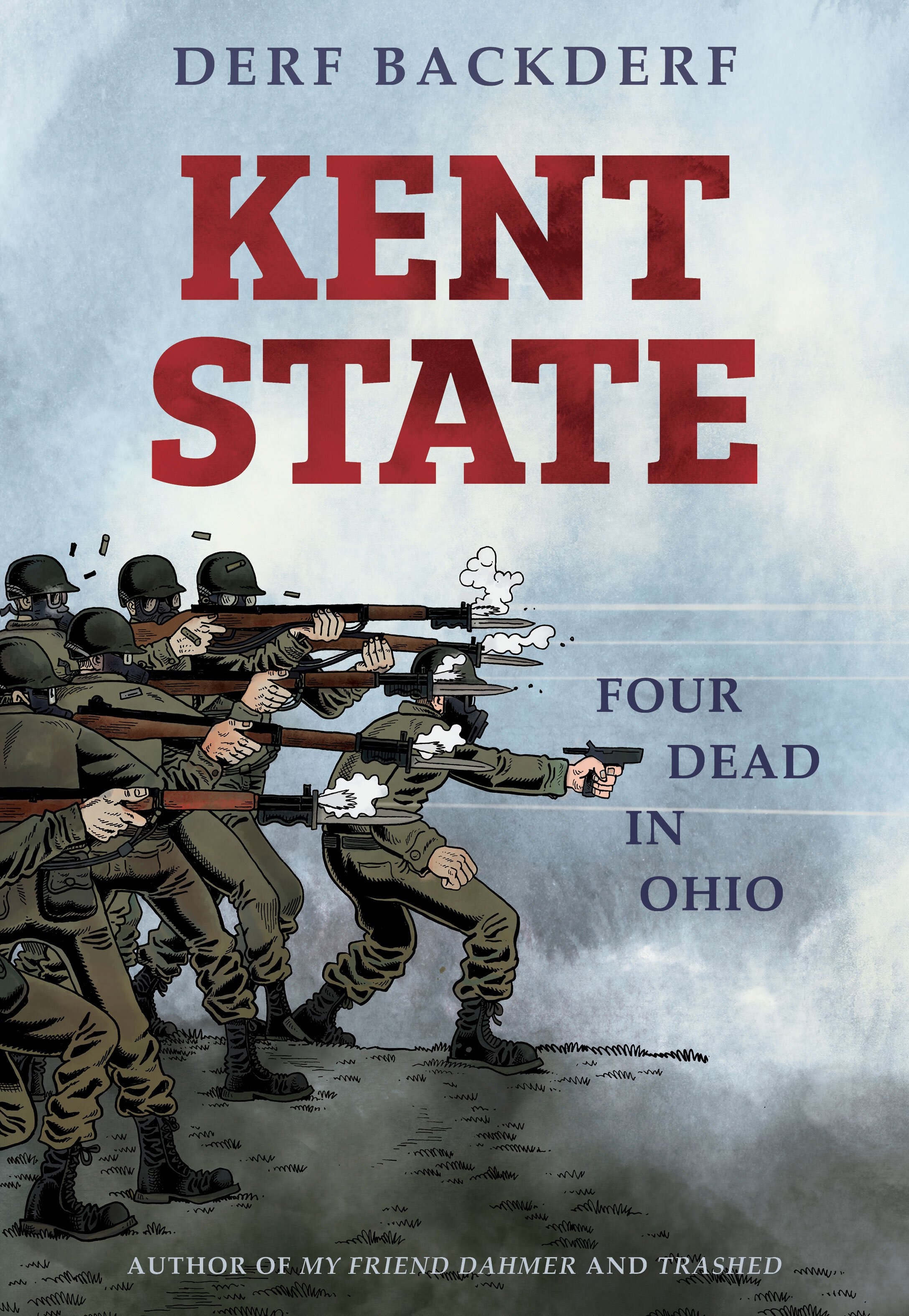

Derf Backderf | Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio | Abrams | 2020 | 280 Pages

2020 is the year, and now is the season, of a very particular remembrance. It has been roughly seventy-five years since the defeat of the Germans in Europe—marked by a White House ceremony dangerous to the surviving veterans themselves—and fifty years since the twin National Guard shootings of students at Kent State, Ohio, and Jackson State, Mississippi. The latter, a historically black college, was bloodier, yet it has not received the same publicity. The former, a slaughter of notably white kids, fostered the hit song of pop memory, “Four Dead in Ohio,” still chanted by millions who lived through those times and countless others, some generations younger. It is hard to think of another song that mirrors so effectively the campus mobilization of the moment.

Artist Derf Backderf, an Ohio native, is himself a most remarkable comics sensation. A political cartoonist most associated with a weekly strip, “The City,” that has appeared in alternative papers for more than two decades, Backderf stunned the graphic novel world with My Friend Dahmer (2010). Who would choose the life of a notorious mass murderer for close examination or the narration of a teen pal?

My Friend Dahmer was a smash hit. Comic stores ran out of copies, and eventually, a film adaptation emerged, something rare if not exactly unknown since the 1940s when funny page favorites Joe Palooka and Blondie were used for low-budget series. No doubt, a better counterpart is American Splendor (2002), the life story of Clevelander Harvey Pekar, that was made into an award-winning film. It was also, notably, about the downsides of life in the USA.

Kent State is meticulously researched, and unlike Pekar, the scriptwriter, Backderf is in total artistic control of his material. It bears the artist’s characteristic punk style. One might describe the slightly distorted, often melancholic figure as perfectly suited to hippies living in a world that they did not choose to inhabit. It also suits military officers, grunts, and cops who do not understand—cannot understand—why in the world anyone would protest a war (or for that matter, protest racism). He more or less captures the tone of the National Guardsmen, young and nervous guys who feel trapped and embittered, even their guns reminding them that they might be in Vietnam soon enough. In my memory, Guardsmen were slightly more prone than in Kent State to actually talk with demonstrators, especially coeds, who approached them and politely expressed their antiwar sentiments. But that may have been another place and a better tactical plan for the Left that went unadopted at Kent State.

The events here move swiftly, even uncontrollably. The antiwar and anti-draft rage of a minority of students catches others off guard. It inevitably upsets the campus undercurrent of miniskirts, the pill, and the first more or less casual sex among white, middle-class young people. In short, the sweeping counter-cultural impulses of the day. More influential on elite campuses with politically sophisticated students, these impulses seem to have come to the more blue-collar Kent attendees suddenly, almost unexpectedly. It would have been better, in some ways, if Backderf had captured the specialness of the Kent State scene. But this is his narrative, and it more or less accurately captures the existing scholarship.

Kent’s recently expanded campus, with many kids from Cleveland or suburbs already feeling out of place, offered a perfect spot for the antiwar movement to arrive, in force, late in the day for the national scene. At Kent, the movement was also very much bristling with hyper-militance. The tactical approach of student activists with years of training, as was common on better-known campuses, was lacking. Nor was there a slightly indulgent college administration, as in many other places, weighing its prestige against the unwanted outcomes of open conflict.

Backderf might also have worked harder to capture the conservative and avowedly racist context or vibe in parts of Ohio, linked intimately to Kentucky and the South since before the Civil War. These districts, influential in state politics, harbored Ohioans eager to see the antiwar movement put down, with extreme violence against the peaceniks offering revenge against all the disturbing developments of the 1960s.

The artist keenly observes that military intelligence experts working at the Pentagon had spies on Kent’s campus. Along with ROTC faculty reports, the efforts of agents working on campus to bring the demonstrators to (in)justice are still classified, fifty years later.

This is a comic that ends with twenty-five pages of “Notes,” marking the artist’s pursuit of accurate details, those found in newspapers, archives of all kinds, and interviews with those on the scene. Backderf is, in short, deadly serious about getting the story right.

It would be unfair to charge Backderf with any lack of accuracy or lack of sympathy for those who suffered most. What this observer of antiwar activities on three other campuses—including the University of Wisconsin at the apex of confrontations—finds limiting is the absence of a certain softness or Flower Power optimism that somehow existed on campuses of the day, along with the rage and violence.

By 1970, Martin Luther King, Jr., along with Bobby Kennedy, among others, had been murdered. Within the antiwar movement, a desperation grew to halt the accelerating destruction of Vietnam as a small jungle country—and the Vietnamese who suffered within it. And yet, “Give Peace a Chance” would be heard along with “Four Dead in Ohio,” and smaller campuses, liberal arts schools, religious, Southern schools and others, saw rising, peaceful protests against the War. This is the vibe unseen in Kent State, and perhaps Barkderf cannot find it there in 1970. I would like to think otherwise.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider making a donation.