A Journey through the Work and Worlds of Arthur Phillips

Arthur Phillips | Prague, The Egyptologist, Angelica, The Song is You, The Tragedy of Arthur, The King at the Edge of the World

Shakespeare introduced me to Arthur Phillips.

In the spring of 2011 I had just bought The Tragedy of Arthur, Phillips’ latest novel, the story of the discovery of a lost play by the Bard.

But why?

In high school I had hated Shakespeare—had sat in English classes trying to read Julius Caesar and Macbeth and could not. (I have the grades to prove it.)

At Hiram College, my freshman year, I once again encountered the Scottish king and once again fell beneath the Bard’s blade. Snicker-snack! Headless.

But in subsequent years—teaching secondary school English and required, one year, to do Julius Caesar and Hamlet—I found something happening to me, something far beyond mere surprise.

I was falling in love with the Bard.

Before long, I was totally ensnared, and by the time I retired, I had read all of the plays and with my wife had seen all of them onstage (yes, even Henry VI, Part Three—even King John—even Timon of Athens).

We’d been to numerous Shakespeare festivals—here and in Canada. But we’d not ever seen Richard II—not until July 12, 2013, at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Massachusetts. When the lights came up afterward, I was weeping.

This could go on. But all of this connects to Phillips this way: I was also reading contemporary novels about the Bard and his plays—or based on them. Among the myriad were Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres, John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius, Eleanor Brown’s The Weird Sisters, David Snodin’s Iago: A Novel, and that wonderful series of novelistic modernizations currently being published by Hogarth Press, novels written by, among others, Jo Nesbø, Jeanette Winterson, Anne Tyler, Margaret Atwood.

So The Tragedy of Arthur was a sensible addition to my obsession.

I just checked my Phillips file folder and discovered a clipping from the New York Times Book Review—a piece about Arthur by Shakespearean authority Stephen Greenblatt. It was the cover story on May 1, 2011.

At the time, I’d never heard of Arthur Phillips—even though, by then, I’d been a book reviewer for a dozen years. (Who can explain it? Who can tell you why? Fools give you reasons ….)

After reading that Times review I promptly bought the book, began it on May 24 (taking copious notes), and finished it on June 7. I loved it. Then I filed those notes and forgot about Phillips—behavior that is unusual for me. When I like a book, I usually dive into the author’s complete works.

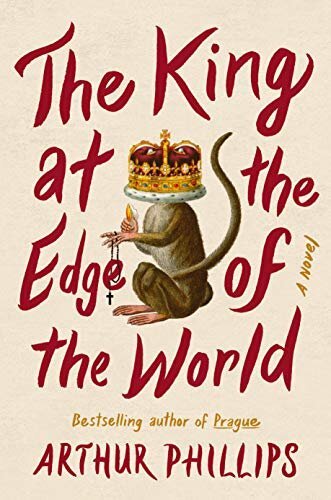

Then, this year, I saw that Phillips had a new novel—The King at the Edge at the World. Bought it. Read it. Loved it, too. And it was then that I began a journey through his others, a voyage I completed in early May this year.

I’m not going to offer detailed summaries of his novels—such things are easily accessible online—but will offer just enough to indicate his varying subject matter. I want to focus principally on Phillips’ style, his techniques, his major concerns.

But first—what about Phillips himself?

On the flyleaf of his first novel, Prague, is a note that he is a five-time Jeopardy! winner—and this is later relevant in his novel, The Song Is You (as we shall see). You can find video of Phillips’ appearances online.

Otherwise, he has had a varied and even remarkable life. Born in 1969, he attended Harvard—and, later, the Berklee School of Music (jazz saxophone). He spent some years abroad—in Budapest and Paris—and, according to Amazon and information from Random House (his publisher), he was a child actor, jazz musician, speechwriter, entrepreneur. He’s written for television (Netflix and others) and lives in New York City with his two sons.

But there’s a paucity of personal information easily available on Google about Phillips. I could not quickly find anything about his family background, for example. Just the items I mentioned above—and comments about his novels. In interviews, he prefers to focus on his work—not on his autobiography. So, let’s do what he does.

His first novel was Prague (2002). The story begins in Budapest (where most of it occurs—don’t worry: the Czech situation is key, as well). We meet four Americans in a café, and each of them has some prominence, principally John Price, a younger brother of another character, Scott. John, who has shown up in the city without warning, gets a gig as a local journalist, and we follow him around. He meets a woman, Emily, who enchants him—and off we go.

The second novel is The Egyptologist (2004), set in the 1920s and involving Ralph M. Trilipush, a young man who’s been obsessed with Ancient Egypt since boyhood; he is currently an adjunct at Harvard University and is off to Egypt to search for the tomb of Atum-hadu, a king whose existence most reputable Egyptologists dismissed. Tut’s tomb also figures in the story.

Next is Angelica (2007), a Victorian ghost story—sort of. In London, Constance Barton is a young mother of a four-year-old (the eponymous Angelica) and wife of a scientist, Joseph, who specializes in experiments on live animals—a profession she’s not at first aware of. Angelica is troubled, and Constance begins to believe there is a ghost in the house.

In 2009 Phillips published The Song Is You, a novel focusing on Julian Donahue, a successful director of TV commercials. His marriage has broken—and he has a brother who’s a Jeopardy! fanatic. Then one night, in a club, Julian witnesses a performance by a young singer, Cait O’Dwyer. He is smitten. And a journey commences—for both of them.

In 2011 Phillips stunned the literary world with The Tragedy of Arthur, a novel about the contemporary discovery of a lost work by Shakespeare, a play about King Arthur. The novel records the attendant flurry in the Shakespearean scholarly community, but Random House (Phillips’ publisher!) decides to publish it. And then … Phillips includes the actual text of the “lost play”—yes, all five acts. (The chutzpah!) Phillips says in an online interview the composition of the novel and of the play were “almost simultaneous.”

Phillips’ most recent novel is The King at the Edge of the World, 2020, a story that takes us back to the latter years of England’s Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603). A Turkish delegation arrives in the country to work out trade deals; a physician comes with them—Mahmoud Ezzedine—a skillful man who saves a courtier apparently having a stroke. The head of his delegation orders him to remain in England (his family remain in Turkey), and he does so for years, becoming involved in the plans (public and otherwise) to smooth the transition between Elizabeth and James VI of Scotland (who will become James I of England).

It’s evident in these brief summaries that Phillips is comfortable setting his stories in a wide assortment of places and times. What’s perhaps less evident is the facility with which he does so. Egypt in the 1920s—Elizabethan England—Eastern Europe in the 1990s—Victorian England? Why not? I have the feeling that although he patently enjoys the writing (and imagining), he also loves the research—the substantial research—that underlies each of his novels.

His technique varies from novel to novel, as well—another sign of a restless, creative mind—another indication that he loves playing with his fiction as much as he does working with it.

Prague is probably the most conventional—though he does use multiple characters and shifts from one to the other throughout.

The Egyptologist is a technical tour de force. There is not a conventional narrative in the novel—just a compilation of documents: interviews, letters, cables, journals, and the like—all of which advance the story in a subtle way—all of which help Phillips conceal his truth until later on.

Angelica also shifts points of view, with sections named for different characters in the novel, and it is through these several characters (the little girl, the mother, the father, the spiritualist the mother has employed) that, again, Phillips’ truth emerges.

The Song Is You—most of which we see through the eyes of Julian Donahue (in the third person)—is different in that we are not really sure if what Julian is reporting to us is what is actually happening in the world—or is perhaps alive only in his mind.

In The Tragedy of Arthur one of the voices belongs to “Arthur Phillips,” who also narrates; he’s a fictional creation, the son of the man who, so believes “Arthur,” has forged the manuscript. We learn a lot about “Arthur’s” life—and about why he has come to believe this about his father.

Finally, The King at the Edge of the World employs a more conventional third-person narration, though we do enter the mind of Mahmoud with wonderful frequency. Phillips divides the novel into parts with titles that are the names of characters who form the focus of that section (as he did in Angelica and elsewhere). The Epilogue, for instance, is “Mahmoud Ezzedine and God.”

On a somewhat more frivolous note: Phillips—despite his seriousness of purpose—can be playful in his texts. I’ve already mentioned the employment of his own name for the narrator of Arthur, and in The Egyptologist I got a surprise when, Googling to see if the surname of the principal character, Trilipush, meant anything, I learned that someone had figured out that “Ralph M. Trilipush” is an anagram for Arthur M. Phillips.

There are other sorts of playfulness, too. In The Song Is You, Julian’s brother has been on Jeopardy!—and ended his time in humiliating fashion. In Prague is a funny sentence about English majors: They have, says a character, “almost no options in the United States after graduation and were forced to become a sort of refugee themselves, deployed to the four corners of the world to teach the only skill they had, which was valuable proportionally to how far from home they wandered.” [106] Phillips sometimes inserts literary quotations, which, I suspect, are of his own creation. Shakespeare pops up now and then, sometimes amusingly so. In Angelica, for example, the ghost-fearing mother and the spiritualist go off to see a production of Hamlet. In Arthur, an actual Shakespearean scholar, David Crystal, plays a wee role.

Phillips deals with siblings, with relationships between men and women (and the hunger for love), with parents and their children, with the idea that the truth—insofar as it exists, insofar as we can know it—emerges best through multiple points of view.

But a big factor in all his stories in obsession—how it motivates us, how it can destroy us, how it can lead to madness. In this regard, some readers will surely remember some of the novels by Ian McEwan—think of The Child in Time, Enduring Love, Amsterdam, and The Children Act, all of which show, like Phillips’ work, the corrosive, implosive power of obsession.

In Egyptologist, Ralph is so smitten/obsessed with Ancient Egypt that he will allow no leash—not scholarship, not truth—to inhibit him. The mother in Angelica is absolutely convinced there is a ghost in her house, a ghost threatening her child, and she will go to extreme lengths to protect her daughter. In The Song Is You Julian pursues Cait, the singer, with a passion and determination that make the word stalker seem feeble.

A journey through the six novels of Arthur Phillips is like a voyage among a group of very different islands—each of which provides a different view of human beings—of how they are different—yet very much the same. And on each island readers see Surprise, that most riveting literary character of all, waving at them from the beach.