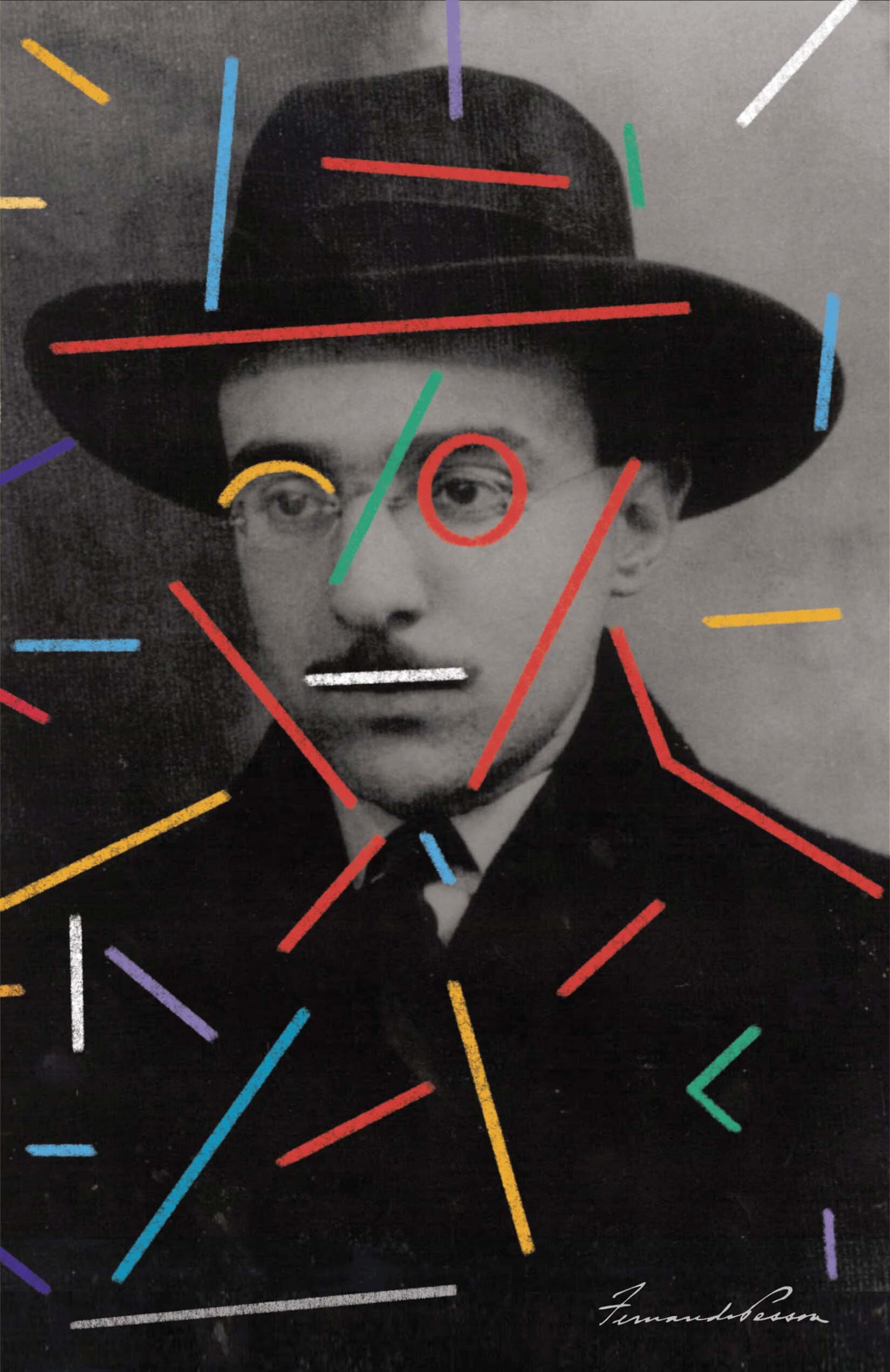

Knowing How to See Without Thinking: On Fernando Pessoa's "The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro"

Fernando Pessoa, transl. Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari; eds. Jerónimo Pizarro and Patricio Ferrari | The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro | New Directions | 2020 | 320 Pages

Growing up in Portugal, fear of Fernando Pessoa was impressed upon us early in school. I remember my sixth-grade teacher reporting on the frustration of high-school students at the chimera-like author with five different heads—all sporting different names, personalities, and bodies of work. I sat my final wondering what head I would get for the expository essay. Alberto Caeiro’s rose intimidatingly from the exam page, and I can say I was ready for the onslaught. The surprise at a mediocre result, and its significant improvement ensuing from a fair revision, showed me something—that beyond the inflexible list of interpretative angles set by the National Education Board, even Portuguese teachers shared in the general perplexity surrounding the intelligibility of Fernando Pessoa’s work.

As far as attempts to understand his work go, The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro is an excellent place to start. Translator Margaret Jull Costa’s biographical note is an accessible introduction to Pessoa, whose heteronyms warrant a conceptually decluttered explanation of their poetic function. Jull Costa’s elegant definition describes the heteronyms as

a term he chose over ‘pseudonym’ because it more accurately described their stylistic and intellectual independence from him, their creator, and from each other – for he gave them all complex biographies and […] distinctive styles and philosophies. They sometimes interacted, even criticizing or translating each other’s work.

She does not engage in scholarly expounding—the introduction by editors Jerónimo Pizarro and Patricio Ferrari, and their notes on Pessoa’s biographical material on these pseudo-authors, take care of that. Instead, Jull Costa paints a picture of the life of a poet who dabbled in odd jobs and rather concentrated in his mostly unpublished and unnoticed poetic work. Her brief list of unremarkable events fairly captures Pessoa’s public life and achievements—the drama of his lifetime would be found inside two trunks worth of thousands of unpublished pieces that documented the career of a prolific and extremely well-educated writer. His mind had developed dozens of pseudo-authors, who he called his heteronyms, and his poetic universe focusing coherently on three—Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, and Ricardo Reis.

Following Jull Costa’s clarifying biographical note, Ferrari’s and Pizarro’s introduction is now comfortably allowed to assume the reader is relatively familiar with this fictional world in which author and character intersect. It storms the reader with the chronological intricacies of the writing and publication of Pessoa’s work—an appropriate task for an edition prepared in parallel with its Portuguese scholarly counterpart, published by Tinta da China. The issue of authorship and intentionality in Pessoa raises confusing and interesting questions that take center stage in most scholarship. Hence, Caeiro’s authorial biography, unlike the real Pessoa’s, is a matter of debate to be settled by the puzzle of fictional dates and actual poetic revision. Ferrari and Pizarro pose the question, when did Caeiro die? We may be forgiven for thinking that this hardly matters if, according to Roland Barthes, the author should be playing dead. However, the fictional Caeiro’s death would be fundamental for his role as the mythical gone-too-soon master who occupies the center of Pessoa’s theatre of author-characters.

Its attention to this theatre is one of the strengths of this new English edition of Caeiro’s body of work. This volume, decked with all relevant commentary on Caeiro by Pessoa and the other heteronyms themselves, promises to shed light on the complexity of Fernando Pessoa’s work for English-speaking audiences. These heteronyms live in the same story, woven out of the poetic conversation between them. This conversation revolves around the same axis: the tragic existential conundrum arising from being made aware of the comforting illusions of our sociolinguistic existence. Pessoa and his main heteronyms all investigate the best poetic devices and philosophical positions with which to cope with this disillusionment. However, it was Caeiro who seemed to achieve the way out of this existential anxiety through his “splendid nonmysticism” as separate heteronym Thomas Crosse puts it. His disciple Álvaro de Campos calls him “the great Liberator […] from hope and hopelessness so that we neither console ourselves without reason nor grow sad without cause; co-existing unthinkingly with the objective necessity of the Universe.”

Alberto Caeiro came to be “upon opening a window” and discovering “that Nature exists”—as a function of itself, not of poetry. Thus, he is established as the outlier to the other heteronyms and their respective coping mechanisms. Pessoa was a nihilist, Campos was a self-professed “sensationist” (with a futurist streak), and Ricardo Reis was a stoic classicist. Uniquely, Caeiro was “a poet of absolute materialism,” as Pessoa himself writes: “Things are to [Caeiro] absolute realities, more real even than our sensations of them. Thought is a disease.”

In Caeiro’s first collection, Keeper of Sheep, this shepherd of “thoughts [which] are all sensations” finds that “To think a flower is to see it and smell it / And to eat a fruit is to know its meaning.” Consistently defending that “things must be felt as they are,” as Crosse puts it, Caeiro is irritated by metaphysical investigations. To think about the “inner meaning of things” is “meaningless,” a delusion borne out of having “to use human language.” In his idiosyncratic blend of materialism, pragmatism, and empiricism, Caeiro weaves such lines as

Someone sitting in the sun and closing his eyes, / Begins not to know what the sun is/ And to think many other things full of warmth. / […] The light from the sun doesn’t know what it does / Which is why it never strays and belongs to everyone and is good.

This bare clarity needs a translator who is not tempted towards the easily verbose transformation from verb-reliant Portuguese towards noun-based English. Fernando Pessoa’s work is lucky enough to be relatively unknown and yet possesses great translators. The handful of translations into English have ranged from bad (Jonathan Griffin) to very good (Richard Zenith). Only two editions focus strictly on Caeiro and his full body of work: Chris Daniels’ translation in Shearsman Books and Michael Lee Rattigan’s translation with Rufus Books. While both are good translations, only the former includes a handful of the main writings on Caeiro by the heteronymical disciples. Jull Costa and Ferrari’s new translation, however, has the supple quality found to be rare in poetry translations from Portuguese to English.

Compared to English, the Portuguese language has a heavier reliance on verb forms. This gives it a higher degree of flexibility, allowing users to creatively and unusually manipulate common phrases towards new ways of delivering ideas. Fernando Pessoa’s poetic style depends on this –heavy verb-reliant synesthesia is a regular stylistic device used by those significant enough to be studied in Portugal’s high-school classrooms. It is often his and Caeiro’s verb play that create the most evocative pictures of their meaning. He takes an idea and pokes at it with verbs from different angles. Compared with the verb-laden lines in Portuguese—“Pensar incomoda como andar à chuva/ Quando o vento cresce e parece que chove mais”—Costa and Ferrari offer an inflexibly prepositional and polite translation—“Thinking is as unpleasant as walking in the rain/ When the wind builds and makes the rain seem heavier”—that fails to capture the nagging weight with which the Portuguese words drag at each other. The rhythmic flow of the poem is often doomed to be broken by the English necessity of a regular subject.

In lines like “Who walked like one imprisoned,” like one is the usual suspect dispersing metaphors into similes. In such cases as the translation from “Ao entardecer” to “At dusk,” one can’t but reduce the Portuguese reliance on states unfolding (in which continuous verbs transform into descriptive nouns) to stationary English phrases. However, Costa and Ferrari shine whenever the impossibility of accuracy provides an opportunity for originality, moving elegantly within that threshold between the translator’s poetic sensibilities and their sense of the poetic persona’s style. Even in unnecessary diversions—such as the translation of “Era poeta d’isto, mas com tristeza” into “The sad poet of all these things”—the loss of the original style gives way to very good lines of verse.

The materials at the close of the book – a set of letters, critical commentary, interviews, and recorded conversations by the heteronyms - helps the reader navigate the three stages of Caeiro’s poetry. According to heteronym Ricardo Reis, the “lucid” meta-philosophical transparency of The Keeper of Sheep is followed by the beginning of his “thought disease” and its late stages, which are captured, respectively, in The Shepherd in Love and Uncollected Poems. Different descriptions of Caeiro’s first philosophy are attempted by most of these heteronyms. Crosse’s nonmysticism becomes Campos’ mysticism of objectivity, both stemming from Caeiro seeing “lack of meaning in all things.” Yet, the heteronymical dynamic included in these pages exposes the existential stakes Pessoa’s pseudo-authors shared. Their conflagration around Caeiro—heightened by this edition’s materials—sketches both the poetic master and the shape of his impossible existential comfort. Initially unriddled by the fear of lack of meaning, he inhabits the state of mind his disciples struggle to attain. However, the poet who deems as diseased and confused the legacy of human philosophy, also admits that its treatment “requires long study, / An apprenticeship in unlearning.” As Crosse finds, “he seems to have his intellect put into his senses” when he philosophically undermines essence: “What we see of things are the things themselves. / Why would we see one thing if there were another?”

A contradiction unto himself, Caeiro is the ironic contrast to the truth Pessoa knows. His mastery of existential detachment and observational clarity results only in intellectual improvement and disillusioned awareness. It is both Caeiro’s eventual thought disease and his contradictory characteristics that underscore the inevitability of the illusions inherent to human language and so, perception.

Ferrari and Pizarro deploy Oscar Wilde, who wrote that “Nature is no great mother who has borne us. She is our creation,” to capture the theme of this poetic theatre surrounding the character-poet who plays a “naïve and simple man who only thinks complexly […] whose spontaneity is the product of deep reflection.”

This new English edition of Alberto Caeiro’s work frames Pessoa’s poetic and philosophical investigation into the limits of language, poetry, and perception. Its complementary heteronymical materials provide the reader with a clear sense of Caeiro’s central role in this investigation. His famous line, “Nature is parts without whole,” captures his therapeutic endeavor to rescue human thought from the muddles our language binds us to. Yet, it is in his “diseased” poetry that we find the recognition of humanity as that which makes us think of the world in terms of “hope and hopelessness.” The illness does not make him optimistic—distance is a function of sight, and “to move closer is to deceive oneself.” Even so, there is a tender sentimentality in his diseased kind of pragmatic acceptance. In the end, Caeiro’s most reliable balm against hopelessness lies precisely in this acceptance of his human vulnerability:

What are the illnesses I suffer and the bad things that happen / to me / But the winter of my person and my life? […] Like everyone else, I was born subject to errors and defects [But] Never the defect of demanding from the world / That it be anything other than the world.