Black Enterprise Reclaimed: Comments from Don Hayner

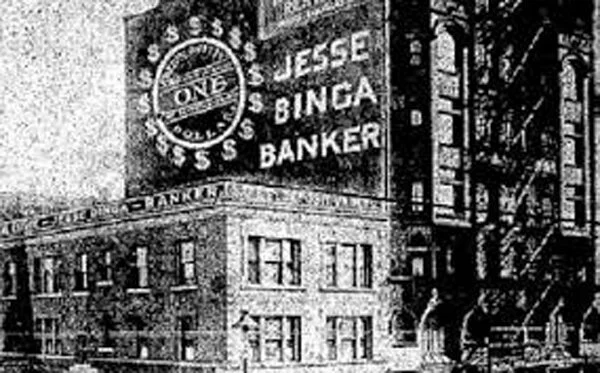

I was heartened and thankful to read Christopher A. Smith’s generous review of my book, Binga: the Rise and Fall of Chicago’s First Black Banker, in the Cleveland Review of Books, particularly in how he put it into context when he said, “the book captures how Black enterprise in America was deferred but can be reclaimed—a lesson sorely needed in this time of pandemic and protest.”

Of course, it’s also sad that this continues to be the context of America.

Binga was more than a banker; he was an agent of change. At the beginning of the twentieth century, he opened parts of the Chicago housing market to Blacks by moving Black families into white neighborhoods. He was an unapologetic capitalist, who also fought the origins of segregation in this, one of the most segregated cities in America. That fight made him a target for continuous threats and bombings, and he became a lightning rod for the deadliest race riot in Chicago history. And to think, that was the context one hundred years ago.

For Binga, his race was an issue for him every day in Chicago. Every day. As I mention in my book, a study done on the 1919 riots said the experience of “ostracism, exploitation and petty daily insults” could have a grinding impact.

I imagine that, for many Black Americans today, it seems little has changed.

Binga was a tough guy who never backed down to racial violence, nor did Black Chicagoans during the 1919 riots. But Binga always emphasized that he never let racial hatred “destroy my soul.”

Still, there’s always been a feeling of daily despair to it all. As Chicago singer and songwriter Curtis Mayfield once wrote, “When you wake up early in the morning, Feelin’ sad like so many of us do…”

As a white man from the South Side of Chicago, I’ve seen the protests, riots, and the tumult of the sixties, but I never realized that the country would watch this happen periodically and in various forms for the rest of my life. It had to end, didn’t it?

America has been witness to a constant ebb and flow of racial tension and turmoil, giant waves of outrage and protest, followed by some change, but never complete change, or maybe never real change.

So now, the question repeats itself: is this time different?

Since the death of George Floyd under the knee of a white policeman, it feels a lot like 1968, but something seems different.

We’ve seen Mississippi get rid of the Confederate flag on its state standard, NASCAR ban it from its races, and Confederate statues toppled across the South. Finally.

We’ve seen some police officers kneel with protesters, and we’ve seen some protesters form a protective ring around a cop to protect him from violent rioters. Powerful forces now appear to be assembling for reform.

Polls and studies show increased national support for the Black Lives Matter movement and a need to press for racial equality. And polls seem to indicate Millennials and the generation born after them (Gen Z) are strong advocates of that push for freedom and equality.

“That is the hope of the country,” Spike Lee recently said in an interview with the Associated Press, “this diverse younger generation of Americans who don’t want to perpetuate the same (expletive) that their parents and grandparents and great-grandparents got caught up in.”

When Miles Davis first went to Paris in 1949, he said it was when he first understood that all white people weren’t the same; some weren’t prejudiced. He called it “an illusion of possibility.”

Let’s hope the possibility we see now is not an illusion.