Refusing Erasure and Enclosure: On Lee Bey’s “Southern Exposure"

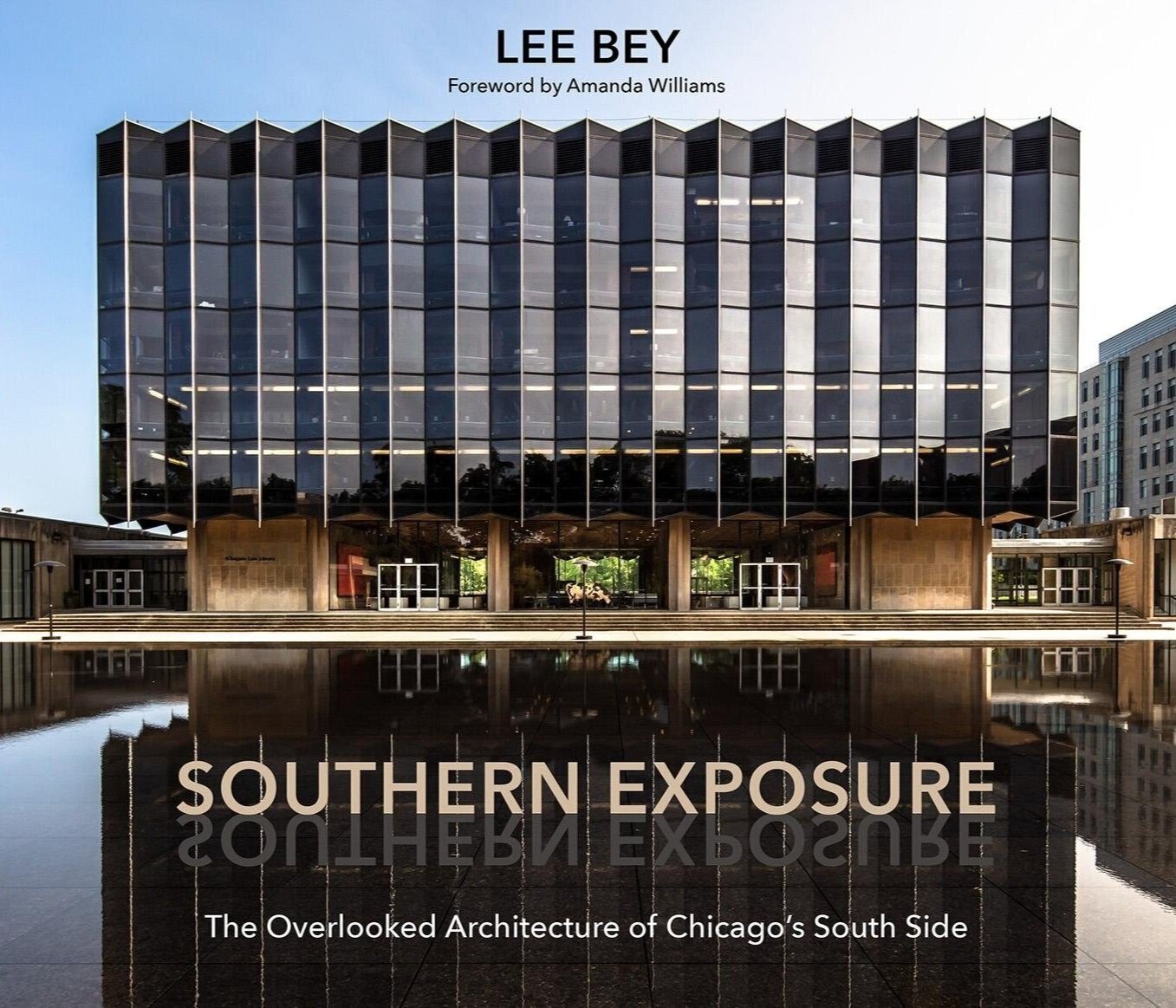

Lee Bey | Southern Exposure: The Overlooked Architecture of Chicago’s South Side | Northwestern University Press | 2019 | 172 pages

In Southern Exposure: The Overlooked Architecture of Chicago’s South Side, Lee Bey photographs the stunning architectural gems of Chicago’s South Side and pens essays that bring each frame to life. Each photograph serves as an entry point to the rich history of the South Side—a geographic area the size of Philadelphia that’s too often been pigeon-holed as low-value and crime-ridden.

Bey reinserts the inherent value of each neighborhood by focusing on the everyday experiences of its residents, both past and present. Using facades and the built-environment, Bey peels back the layers of historical systemic disinvestment. Southern Exposure thus raises the question—who is overlooking an entire side of the city, and what’s the human impact?

In 1981, a 14-year old Lee Bey hopped in the car with his father, not knowing he was about to inherit a history of innovation and resilience. Riding through the Grand Boulevard and Douglas neighborhoods of Chicago’s South Side, Bey’s father described the built environment’s rich history, clear in his memory but obscured through divestment and decay. Whatever broken buildings Bey saw from the street were made vibrant again, as his father told stories of the spaces in their prime. Passing everything from stately brick-buildings to a rusticated bell tower, Bey describes this car ride as an architectural “bequeathing.” A year later, his father passed away.

This memory frames Southern Exposure and has clearly shaped Bey’s entire architectural pedagogy. Bey—a former Chicago Sun-Times architecture critic, deputy chief of staff for urban planning under former Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley, and current photographer, writer, and lecturer—has dedicated his life to examining the political, social, and racial forces that shape spaces and places.

A born-and-raised South-Sider who works and resides in the communities he advocates for, Bey is deeply invested in the value of the place he calls home. His 20+ year career in Architecture and Urban Planning shines through every page of this book, helping to bring out the complexity and nuance behind every photograph.

Southern Exposure departs from the commonplace practice of photographing solely the disposal, demolition, and destruction of the South Side. While some photographers swoop in to snap pictures of dilapidated buildings, what they end up doing is flattening a history, fueling a master narrative, and continuing to offer up a single story of diminishing value. Bey operates from a different moral imperative. He writes, “Demolition is the end of an act—the curtain fall, if you will—that starts years earlier with civic neglect and disinvestment caused in no small part by the institutional racism that seems to always kick in when a neighborhood is predominately black.” Bey’s approach places every vacant lot or shuttered home into a continuum of disinvestment, an active timeline that allows you to see the policies that shaped the space.

Each chapter takes on new neighborhoods, and Bey begins with the historic district of Bronzeville. Often named the Black Metropolis, Bronzeville housed an influx of Black Southerners who moved to Chicago during the Great Migration in search of industrial work. Escaping one system of enclosure—enslavement—Black people believed better opportunities existed in urban, industrial areas. Originally designed for white upper-class residents as the original “Gold Coast,” Bronzeville turned into a predominantly Black area due to white flight in the 1920s and 30s. This city-within-a-city became a symbol of Black economic mobility and innovation as Black-built buildings and businesses formed Chicago’s Black Wall Street.

Today, it’s clear that the systems of enclosure only shapeshifted. Many edifices of Black Wall Street were demolished in the 80s-era of “urban redevelopment,” and after demolition, the city failed to reinvest in the neighborhood. When faced with the erasure of the built-environment, preservation groups, journalists, and activists fought for landmark status, which was granted in 1998. Since then, there have been waves of revitalization, but the city’s failure to comprehensively commit to reinvesting in the entire South Side becomes a pattern in Southern Exposure.

Bey’s book documents the various policies and practices that have shaped the contemporary landscape of the South Side, ranging from the restrictive covenants in West Pullman, where white homeowners were legally allowed to refuse to sell to black people until nearly 1950, to the 1997 demolition of a mile-long section of the CTA Green Line tracks along East Sixty-Third Street, which connected Cottage Grove to Jackson Park and the lakefront. Moreover, racist valuation, discriminatory lending practices, and redlining are all explored in depth. Photography helps make these abstract policies visual and visceral.

Bey’s work in documenting the South Side’s built-environment goes beyond the beautiful coffee-table book that it is—Bey’s work is critical in closing an archival gap. Bey refuses erasure by filling Southern Exposure with memories, movement, and stories. By centering the everyday experiences of Black people inside and around the featured space and places, Bey creates a contemporary architectural interiority that is both timely and timeless. What could have easily become still-life in the hands of another artist becomes vibrant in the hands of Bey.

This richness brings to mind the work of Torkwase Dyson, a visual artist focused on the history and future of black liberational spaces. She coined the term “Black Compositional Thought,” which hypothesizes that the energy and movement Black people bring to spatial environments can offer a path towards self-liberation. She looks at people throughout history who used interstitial spaces to self-liberate. Those histories include Harriet Jacobs, who hid in the crawl space of her grandmother’s home for eight years to escape slavery, and Chicago’s own Eugene Williams, who, in 1919, built a raft to visit an island in between two segregated beaches on the lakefront. The question at the heart of her work is this: how do Black people navigate the systems of enclosure that show up in the built environment?

What Bey manages to do with Southern Exposure is shine light on both the systems of enclosure and the self-liberation residents have practiced while living in their neighborhoods. All of this leads readers to ask, where do we go from here?

In the face of continual enclosure and disinvestment, it’s clear that exodus is a path Black people are actively taking towards self-liberation. In Chicago, neighborhoods that were once brimming with residents are drastically dwindling. And just a few weeks ago , WBEZ and City Bureau released an investigative report on the disparate mortgage lending practices in Chicago, causing activists to call for reparations for years of lost investment. Reporters found that out of the $7.5 billion in home purchase lending administered by Chase Bank between 2012 and 2018, only 1.9% went to Chicago’s Black neighborhoods.

So, the question becomes, when will the city start equitably investing in the South Side? In concluding the book, Bey puts rightful pressure on Chicago’s current mayor, Lori Lightfoot, to make a comprehensive plan for the South and West Sides of the city. Bey writes, “There is an open and ongoing discussion among black people that we are no longer welcome in Chicago and that the city’s government, civic leaders, and policymakers are purposely chasing black people out of the city by not fully reinvesting in the South and West Sides.”

Southern Exposure refuses erasure and documents the way people have created communities in the midst of systemic enclosure. Ultimately, Bey’s book is an archival insistence on acknowledgment, asserting—we are here, we’ve been here, will you see us?