Laughing with Dostoevsky’s Idiot: On Lars Iver’s “Nietzsche and The Burbs”

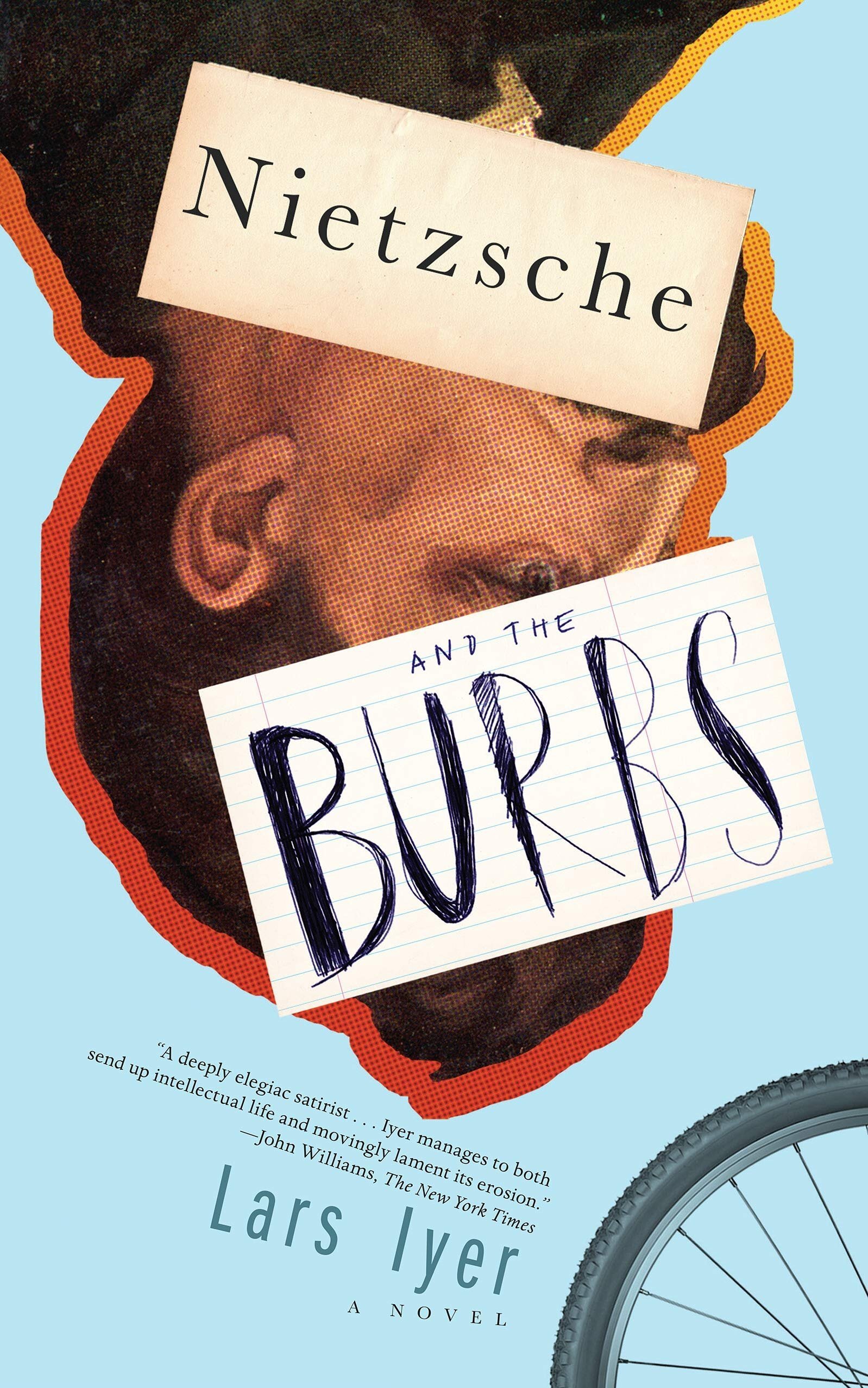

Lars Iver | Nietzsche and the Burbs | Melville House | 2019 | 352 Pages

Ok, fine, I’ll confess that I am a Bo Burnam fan. There’s just something so amusing to me about the surrealness of watching a comedian enthusiastically strike happy chords on a piano while crooning out lyrics like “Stick your tongue in a plug / Suck a pipe of exhaust / Make some toast in the tub / Nail yourself to a cross.” Some might find these lyrics of Burnam’s in the song “Kill Yourself” offensive, but that’s kind of the point. Burnam is smart enough to turn the song into a half-hearted critique of consuming pop culture as therapy. Still, he does so ironically, because the whole point is not that there’s a point but rather that violating taboos can be hilarious.

Lars Iyer’s latest novel, Nietzsche and The Burbs, features many passages situated in a Burnam-esque mode. The novel’s principal cast of characters lends itself to this absurdism. Chandra (our narrator) and his friends Paula, Art, Merv, and the new kid they’ve nicknamed Nietzsche, are a moody group of precocious British high schoolers who start a metal band and discuss nihilism and the end of history between classes and bike rides. Our protagonists wrestle with sexuality, with family relationships that have long since soured, and with all the grade-induced anxieties of contemporary schooling. But mostly, our protagonists wrestle with meaning or the lack thereof, and with the internal conflict of wanting meaning but not wanting to be duped, deceived, or domesticated. Iyer wants readers to take these characters seriously, in the sense that we grow to love them and sympathize with their interior work of becoming. But Iyer also wants us to laugh at them (and maybe by extension ourselves).

We laugh, for example, when the group gets buzzed on vodka and walks the streets “red-faced, euphoric,” yelling, “we own the fucking suburbs.” Similarly, when the group ruminates on the question of whether or not they should commit suicide, we see the humor in the following exchange:

That’s a good question, I say.

She has us there, Art says.

You do it first, Art, I say.

No, after you, Chandra, Art says.

To be clear, teens killing themselves is not a funny subject. Burnam acknowledges as much when he remarks, “suicide is an epidemic”; Nietzsche does the same when he observed that “half of our school are cutting themselves and drugging themselves and starving themselves.” Nevertheless, there is something funny about teenage melodrama and the fact that pretentious-yet-sincere reflections on suicide can resolve themselves in this kind of you-go-first banter.

Early on, our protagonists rhetorically ask themselves, “why are we so tired, at the peak of our lives? Why are we falling asleep, at the peak of our lives?” The novel plays coy, eschewing even the hint of trite answers. There are no 12 maxims for life on offer here, but specific themes do nonetheless emerge. Why are we so tired? Maybe it’s because “we’ve been overstimulated. Overprogrammed. Everything has been done for us. We’ve been grade inflated. Infotained. Our teachers have been like magicians at children’s birthday parties.” Maybe it’s because God is dead, and we have killed him: “the meaning of the world has disappeared.” Perhaps it’s the emptiness of bourgeois existence: “Do we really think it’s possible for us—a suburban romance? A suburban courtship? Do we really want to set up home in a suburban housing estate? Do we really want to send our children to suburban schools, and start the whole cycle again?” Or perhaps this is just the end state of liberalism, of classical liberalism, of neoliberalism, or of a post-liberalism that sets itself in opposition to neoliberalism only to revert to it later on: “Look—the end’s come and gone, Paula says. History’s over. History’s ended. There’s not going to be some great climax. Just entropy, just a kind of fizzling out.”

Of course, as the title would suggest, the problem is also the suburbs themselves. “You die of the suburbs,” one of the gang reflects, adding that “although you think you die of cancer, or of heart disease...The suburbs seep into you. Drip into you. It’s subtle. You don’t really notice it.” And maybe that sounds a little teenage angst-like, but then again, the literary giant Flannery O’Connor once wrote a letter to a friend in which she observed that “if you live today, you breathe in nihilism.”

Every teenager wants to feel unique (don’t we all want to feel original?); every teenager wants to feel like the world is dynamic, evolving, an invitation to sheer potentiality. The suburbs are self-enclosed, artificial, sterile: “New houses, in tiny plots of mowed grass, with no sense of where they are. With no awareness of themselves.” Our protagonists are bored and indignant and hopeful and bored again: “we’re drowning in it: the same, the same. We’re capsized by it: the same, the sameness of the same.” This observation that ultimately endless consumption is not a lasting source of meaning is the critique of liberalism embedded in the end of Fukuyama’s original essay on the End of History: life under liberalism is flat, vapid, soulless. We have our microwaves and our weighted blankets and our Pornhub, but we’re bored to tears. “The worst thing about Wokingham,” our protagonists tell us, “is that it smiles back at your despair. Wokingham hopes that you’ll have a nice day in your despair.” And again, I hear echoes of O’Connor, who wrote that ours is “an age that has domesticated despair and learned to live with it happily.”

I can feel the tone of this piece start to teeter into seriousness. Permit me an interlude to restore us to some semblance of the Burnam-esque mode of inquiry in which we began. Picture this: Nietzsche and his friends at a party, trying to talk to girls (and boys), trying to deal with the uncomfortable realities of being a high schooler with a high schooler’s hormones. Am I discarding the ascetic life of the philosopher if I drink beer instead of vodka or if I butcher some lines from one of the romantics? What if she’s not at all interested in philosophy, but I kiss her anyway? How seriously am I to take all of this? Simply put, are we philosophers, or are we just play-acting? You see this sort of playful ambivalence, a balance of earnest and overwrought, sincere and sardonic prose, in this delightful discussion:

So what actually is nihilism? I ask Nietzsche.

Nietzsche: Nothing-ism. Not believing in anything.

Sounds interesting, I say.

Nietzsche: It isn’t interesting. It’s devastating.

But no, perhaps I am too hasty in foregoing the serious. Because what if you can’t live happily with despair? Are we resigned to suicide or thoughts of suicide or attempts at suicide, or else the numbness of consumption and pop culture and designer drugs to distract us from the despair? At various points, our precocious teenagers ask themselves some variant of this same question, do the suburbs mean the impossibility of philosophy?

In one of my favorite passages in the book, the protagonists savagely dispense with three archetypal life patterns observed in the suburbs. First on the list is the hedonists, described as the “you-only-live-once types. The bucket-list types, dancing with glow-sticks at the Full Moon Party.” There is a certain lack of care in this lifestyle that immediately rules this out for our protagonists who much prefer the life of the mind. Second, there are the career-builders, described as “the Personal Challenge types. Showing signs of initiative, of get-go. Enhancing their CVs. Doing the things potential employers like to see.” The kids have learned to lie to various teachers, to say they plan on studying business at university (“business studies, specialising in marketing, sir”) because business degrees lead to jobs. But the idea of competing in the endless rat race is obviously distasteful for a group who are appalled at the circularity of suburban life. And finally, there is the worst group, aptly described as “the gap-year Do-Gooders. Smug-o-naunts who’ve voyaged halfway round the world for charity.” It is less clear to me why our protagonists should begrudge others of their idealism, except insofar as that idealism is unfounded, or perhaps out of undisclosed resentment that anyone could find it within themselves to believe in any ideals at all.

But if not any of these ways of living, then what is available to us for a meaningful life? As a metal band, maybe the proper mode of living is found in artistic creation. In playing so heavy that you can feel the mass, as the characters memorably describe it. But wait, isn’t art just artifice, another form of delusion, another numbness? And besides, isn’t artistic expression just another opportunity to perform oneself in the layers of self-conscious irony, winking at the audience winking at you for winking at them? Perhaps. But then there is this tantalizing line: “maybe we’ve got to play against our cynicism, Paula says. Break through to something.”

I think the something to which our young friends can aspire toward might be “a philosophy of The Idiot.” Dostoevsky is a recurring source of imagination for our protagonists, and particularly the kind of divine madness found in the character of Prince Myshkin in the novel The Idiot. Myshkin is a holy fool: he lives in a mode that is somewhat more sincere, less contrived, more innocent, less calculated than does the rest of us. And perhaps it is this striking simplicity that lies on the opposite side of the cynicism. “We imagine it: a philosophy of cosmic solidarity. A philosophy of resurrected life.” And of course, this cannot have the last word, or at least we can only imagine it as one among any number of plausible philosophies. We can believe it, but with half a heart and one eye winking.

There are no easy maxims, no 12 steps to your best life now. And the problems this book addresses, from mass consumption to the rise of unchecked corporate power to the hollowness of life under liberalism, are well worth our continued attention. Yet the novel encourages us to adopt a certain kind of hopefulness, so that when we have ceased our ironies and our laughter, when the Burnam-esque absurdities no longer suffice, maybe it’s Dostoevsky’s Idiot who will have the last laugh. Possibly his laugh won’t be just another expression of nihilism, a contempt for all created things. Perhaps his laughter will be more like the communal banter that endears us to Iyer’s characters, and which is itself a sympathetic affirmation that existence is good, that our individual lives are good, and good that we exist together.