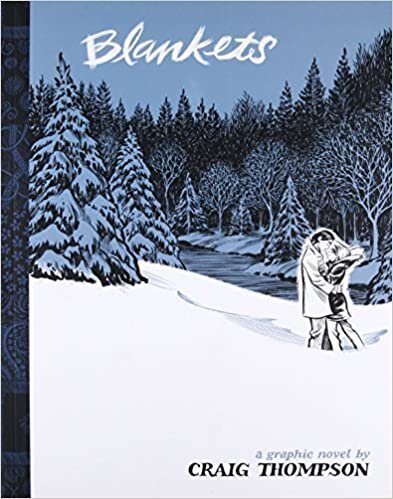

'I Think We Gain a Lot By Enduring These Winters': On Craig Thompson's "Blankets"

Craig Thompson | Blankets | Top Shelf Productions | April | July 2003 | 592 Pages

Early in Craig Thompson’s graphic memoir Blankets, a dad tells a dad joke. The four seasons of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, he says, already cracking a smile, are “early winter, mid-winter, late winter, and NEXT winter—HA!” He is driving while speaking; the panel depicts him from the back. In the rearview mirror his eyes prod his passengers for a reaction. Those expectant eyes, and that punctuating laugh, say much about Thompson’s own eye for the revealing detail. The joke itself is not very good, maybe not even a joke, but it is at least true: in the upper Midwest, winter is the default state of life—the warmer seasons are temporary departures from the norm, to be regarded with suspicion.

The dad goes on: “I think we gain a lot by enduring these winters. We experience a discomfort that may be foreign to others, but that pain opens up a world of beauty.” Here, even the most unreflective reader thinks, is an important line. It is also a fair sample of Thompson’s wooden prose—but then no one reads Blankets for the words. It is first and foremost a book of extraordinary images: across its 582 pages, Thompson employs a half-dozen drawing styles, elegant visual rhymes, and inventive page layouts with a gusto that would be exhausting, not to say pretentious, were it not so finely tuned to serve the story. Almost immediately on publication in 2003, it was enshrined as one of the classic graphic novels, the ones read even by people who don’t know the medium. Thompson worked on it for four years, without a publisher, doing odd jobs around Portland, reading Proust. He was 27 years old.

Blankets is a winter story and a Midwestern one, recounting Thompson’s coming of age among earnest evangelical Christians in rural Wisconsin and Michigan. Most of it takes place in the winter of 1993–94, when he was an artsy, grunge-inflected high school senior with requisite thrift-store cardigan and River Phoenix hair. While moping at church camp he meets Raina, a fellow misfit, and plunges into a teenage infatuation with her. Mixtapes and letters are exchanged, and finally, having assured his mother he will sleep in the guest room, Craig is allowed to stay with Raina’s family for two weeks. There they talk wide-eyed philosophy by day and spend (just barely) chaste nights in her bed before sneaking apart in the early morning.

Young Craig is an earnest evangelical himself, and Blankets depicts the tendencies of his tribe with loving accuracy—the way, for example, he thinks in Bible verses. In one beautifully executed sequence after Raina suggests spending the night together, Craig is beset by a dozen passages about sin and its consequences as he changes into pajamas. Once Raina appears in her nightshirt, his dread is swept away in a rapture that finds expression through the Song of Solomon: “You have stolen my heart, my sister, my bride” (The constant churn of lust, guilt, and jerry-built justification will be familiar to many who grew up in similar circumstances). Almost inevitably, Craig’s time with Raina sets thoughts in motion that ultimately lead him away from faith, family, and region.

We know this song. But Thompson’s rendition contains touches of uncommon grace, such that we are pleased to hear it again. Chief among these is his evocation of the long, deep northwoods winter. Snow is everywhere in Blankets: it begins falling the moment Craig meets Raina, and again when they first kiss, and is falling still when he lifts his gaze to the window from her sleeping form. It is the medium of his rare happy childhood memories (“Winter was our playground,” he says), and a means of pacing the story—panels of the winter landscape, always with bare tree limbs that resemble reaching arms, often frame the narrative beats.

Blankets captures how winter enchants not only the outdoors but the indoors too, how it provides a pretext for often-aloof people to seek intimacy. The best way to keep from freezing, after all, is to get close to someone else. One’s family and lovers become a source of real and metaphorical warmth, kindled through the solitude enforced by the weather. The blizzards Raina and Craig are perpetually caught in cut them off from the broader community and make their immediate one necessary. Occasionally Thompson removes the panels from around his lovers so they are swaddled in the whiteness of the page, as if under blankets of snow.

There is a spiritual aspect to this intimacy as well. During a worship service at church camp, the book’s camera pulls away from Craig, awkward and silent amid his peers’ singing, out of the chapel and into the snowy night, where the clamor of the service is swallowed up by the peace and silence of winter, a deft illustration of the difference between loneliness and solitude. It is the latter where Craig meets God, and where he prefers to be with Raina, alone together (he is deeply uncomfortable to learn she is popular at her school). “The PERSONAL savior concept is what appealed to me,” Thompson the narrator says, speaking of Christianity but also describing the nature of his feelings for Raina.

Through this patterning of images, Thompson equates the Midwestern winter with Raina, and both with salvation—at one point, she sings him a line from the Cure’s “Just Like Heaven.” And in Blankets, winter is heaven. This is well-marked territory in American literature. Consider Emily Dickinson, channeling the prophet Isaiah to describe the New England snow: “It makes an even Face / Of Mountain, and of Plain” (how simple to accomplish in the Midwest!). Or, to stay within the region, this moment from an Ohio winter in Dawn Powell’s My Home is Far Away:

Outside was a magic night of crisp twinkly stars, snowmuffled cottages and white trees. Aunt Lois drew the sled down the middle of the icy pavement, for the sidewalks were filled with drifts. This was indeed growing up, Marcia felt, to be out after bedtime in the dead of night and in the middle of the street.

Of course, such moments end: Dickinson’s snow “stills its Artisans - like Ghosts,” Marcia’s sled ride will end at her mother’s deathbed. Craig returns home and finds he and Raina cannot maintain the febrile heights of their visit over the phone; they grow apart. Over the rushed final act of Blankets, spring arrives and Craig leaves Raina and his faith all at once, a process framed by a retelling of Plato’s allegory of the cave. Enlisting Plato—never mind the timeworn structure of the Bildungsroman—implies this is a necessary step towards maturity. “So imprints on the snow fade in the sun,” says Dante of his own lost vision of paradise, and so Craig concludes that winter is a kind of fantasy, and so is heaven, and so was Raina.

It is difficult to determine the extent Thompson the author approves of this conclusion. Certainly pains are taken to give Raina and her family full lives, with troubles that exist before Craig arrives on the scene and persist after he leaves. These struggles on the margins of Craig’s fantasy hints at his selfishness, not less upsetting for its naivité. He comes on too strong, he objectifies Raina—his most rapturous praise is reserved for her sleeping figure. When she asks him for space, he is too wounded to reflect that she might really need it—her parents are getting divorced, she is increasingly charged with care for two siblings with developmental disabilities, her future is uncertain.

This might read as a wiser man looking back on his youth with embarrassment, if it weren’t for that carefully crafted imagery of heaven. Thompson’s decision to leave Christianity, which he is largely proud of (the reader may be less impressed with the dimestore agnosticism that has supplanted his dogmatic faith), is difficult to untwine from his breakup. It is hard to trust Thompson is merely subtle—one wonders, as in the moment (played as romantic) where Craig masturbates onto a blank sheet of paper, whether the book’s meaning has outfoxed its author.

The essayist Phil Christman has spoken of the tendency to view the rural Midwest as a “fund,” a source of raw potential ripe for extraction by (often eastern) outsiders, as opposed to a place populated by actual human beings. As an economic fact this is incontrovertible, but it may also be a cultural truth. The Midwest’s main artistic export is narratives about itself, whose most famous tellers—Fitzgerald, Cather, Hemingway—left and only revisited in writing. In Blankets’ coda, Craig returns to Wisconsin from the big city. Rummaging in his family’s crawlspace, he unearths the last momento of Raina, a blanket she sewed for him. That night he dreams of her—silent, purely physical dreams—but it never occurs to him to wonder what happened to her, where she is now. Remembering what she gave him is enough. The reader, like a proper Michigander, may find the winter is not so easily dispelled.