Why Do You Laugh? On Philip Metres' "Shrapnel Maps"

Philip Metres | Shrapnel Maps | Copper Canyon Press | April 2020 | 94 Pages

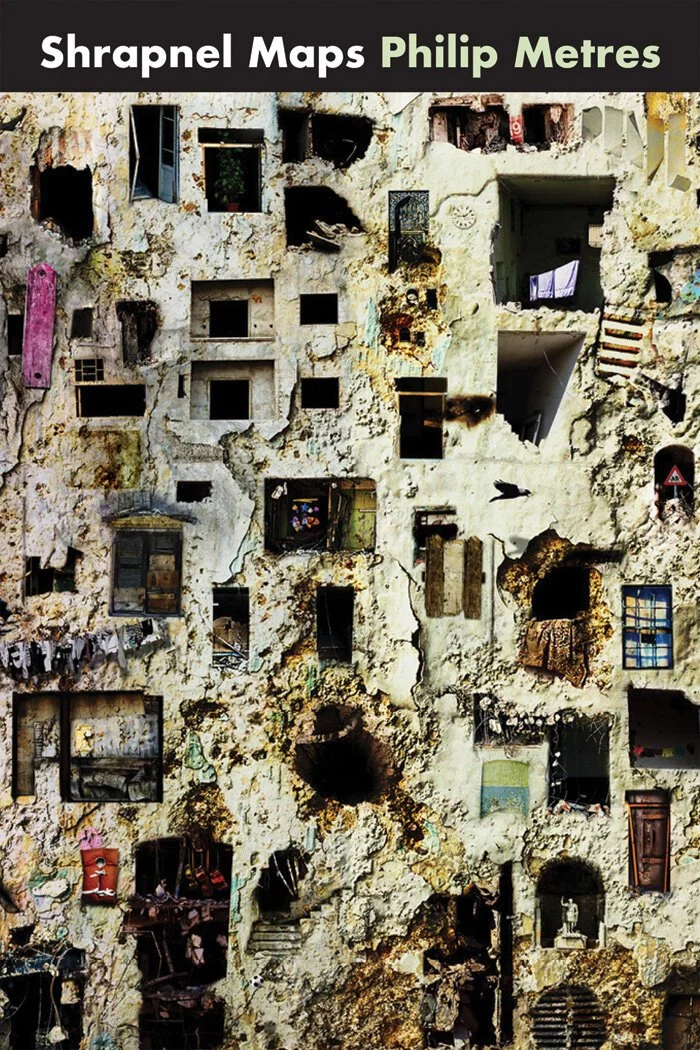

On the subject of Shrapnel Maps’ cover, Philip Metres has said, “Here it is: a building, clearly bombed, but not without life. Each dark aperture invites our eye, suggests some life that’s hard to see at first. Like the poems of Shrapnel Maps, which open into intimate worlds, almost unimaginable from the stark outside.” The immediate consideration to be entered into on these grounds is the ways in which violence effaces personhood and its properties—the fractured self in response to attrition, what life is salvageable in the aftermath, whose stories are told. However, while Shrapnel Maps does concern itself with these topics, it is more-so interested in the potential for healing. Instead of centering the violence committed against Palestine, it centers the people experiencing it while trying to catalog and excavate their history. This leads me to consider the implications belonging not only to a curated tenderness but also the ways in which it could shape a worldview; I am thinking now not of the ways revolution can incur bloodshed, but of the ways in which such a revolution can incur peace, and what it would mean for it to do so. I am of the opinion that this is precisely what Shrapnel Maps asks us—what would it mean to center peace in the solution to the Palestinian conflict?

Do not misunderstand me, I am not simply gesturing towards a peace entirely defined by a lack of war. Muriel Rukeyser, who, like Metres, was a noted documentarian poet, warns us in her book The Life of Poetry against such a narrow-minded definition—

“If we look for the definitions of peace, we will find, in history, that they are very few. The treaties never define the peace they bargain for: their premise is only the lack of war…One present meaning of peace is offered as “rest, security.” This is comparable to our “security, adjustment, peace of mind.” The other definition of peace is this: peace is completeness. It seems to me that this belief in peace as completeness belongs to the same universe as the hope for the individual as full-valued… Suffering and joy are fused in growth; and growth is the universal. A society in motion, with many overlapping groups, in their dance. And above all, a society in which peace is not lack of war, but a drive toward unity.”

Rukeyser is seeking a new definition of peace, one that eschews traditional definitions wherein the conflict is centered. Metres’ book does precisely this, using the language of violence as a secondary consideration and instead progressing as an amalgamation of voices. The very action of constructing a collection in this way fits in with Muriel Rukeyser’s ideal definition of peace. The collection is attempting completeness in the way that it endeavors to paint a picture including every vantage point. Now to be able to see a situation from all sides is truly a remarkable feat, one that would take omniscience, but while Shrapnel Maps falls short of omniscience, it does make remarkable strides towards a concordance of human perspectives and a unity of voices. However, the voices which speak loudest are those of the people belonging to the land.

Yes, belonging is a fraught term, one that asks the meaning of possession and home, but Metres foresees this predicament, and addresses it not only within the poems (Unto a Land I Will Show Thee): “As with a map, as with narrative / Any chosen detail necessarily blots out / Proximate details,” but also in the book’s afterword, quoting Palestinian poet Ghassan Zaqtan on the subject—

“We have many civilizations in this place…And if we accept that we are the conclusion of all of these histories, the narrative will be clearer. Some start history with the Battle of Ajnadayn, when the Muslims invaded Palestine 1,300 years ago, as if there is no history before that. This ignores 10,000 years. The Israelis start with the Hebrews’ journey to Palestine. They ignore what happened after and they ignored what happened before…It will never end that way. If you want to belong to this place, you have to belong to all of its history and respect 10,000 years of several civilizations.”

Metres expounds on this point, concluding that “Zaqtan calls us to a wider memory, and a wider sense of belonging, where no one is erased by another’s dream of a place.” In the collection Metres strives for this wider sense of belonging in a host of ways—observing the optics of Palestine to a visitor in the section “A Concordance of Leaves,” where the poems follow his family on a trip to Palestine for a wedding and recall the strife and militarization contrasted against staunch depictions of joy; the section “Theater of Operations” is a series of sonnets composing a monologue responding to a fictional suicide bombing and is told from twenty-one separate points of view; “Unto a Land I Will Show Thee” gives voice to the land and its cartography; “Returning to Jaffa” concerns itself with the histories and experiences of Palestinian refugees, specifically that of Nahida Halaby Gordon.

The poems themselves often take interest in humanity, its multifaceted presentations, like how sacrificial love demonstrates itself in clandestine ways and what we would give for another’s safety and happiness (One Tree): “Must I fight for my wife’s desire for yellow blooms when / my neighbor’s tomatoes will stunt and blight in shade? Always the / same story: two people, one tree, not enough land or light or love. / As with the baby brought to Solomon, someone must give. Dear / neighbor, it’s not me.”

There is a thread that runs through the collection considering how far the self can stretch and what boundaries we can inhabit (Three Books): “Yes, the sky was the sky, / and the land was the land, / but we had to find / where the book ended / and where we began.” Metres uses this to consider the intricacies of belonging to a thing greater than one person (A Concordance of Leaves): “a country is more important than one person / you’d carry its quandary ten years / around your wandering / & now this country draws you / the way olive roots welcome far water.”

The collection is long and would be impossible to encompass in all of its aims with a single review. However I would be remiss if I did not mention its scathing critiques of nationalism and colonialism—entering into a long lineage of documentary poetics by excavating maps, postcards, guidebooks, holy books, and photographs, along with the testimonies of people related to the land. He depicts the dire conditions of the new apartheid occurring in Gaza, Israel, and Palestine (5. Yael):

on a bus to Tel Aviv to protest the “peace”

my friend’s mother was shot & killed / she left seven

children / seven children / at last I understood

someone will always want to kill us / to erase

us again & now we say we will not let them

& in the mountain’s fold / touched by her blood

the foundation we shall build

I am trying now to gesture towards a certain kind of grief, which Metres demonstrates so well in the book, but I am finding myself lacking the words to describe the way in which grief fosters madness and dilapidation, the ways in which it can strange a person, which Metres recognizes. The book does recognize violence in many forms but also recognizes the systemic issues perpetrating the violence and doesn’t scapegoat individuals or groups (When It Rains in Gaza):

“There is no us.

There is no them.

That by late light

this night, you read

until you believe

the wall will fall

the siege will end

and missing walls

will rise again.”

Above all else, this collection stakes its claim in the histories of people and what shapes them. It implicates more than just nation states and groups, writing into the very heart of the individual, recognizing the many flaws that permeate each of us, often marking more similarities than differences (My Heart like a Nation): “like you, I’m half animal / and half angel, uncertain / where my tenderness ends / and cruelty begins.” This is a breathtaking collection, unrivaled in scope or execution, fit to dwell among the great collections of our time. I have not read a book this formidable and exciting since Tyehimba Jess’ Olio. Yet what sets Shrapnel Maps apart from many of its contemporaries is its insistence on reaching for the light, in reaching for unity, in reaching for new definitions of peace and new definitions of a sustainable joy. It asks how can a people and a land so embattled in history rejoice in a viable way, and it answers (A Concordance of Leaves): “why do you laugh? / because I still have my tongue / there is a song.”

This review is part of the CRB x Barnhouse Series, which was created in partnership with Cleveland press and literary collective Barnhouse in order to better highlight recent poetry releases. Learn more about Barnhouse here.