Extensions of Empathy: On Alan Shapiro's "Against Translation"

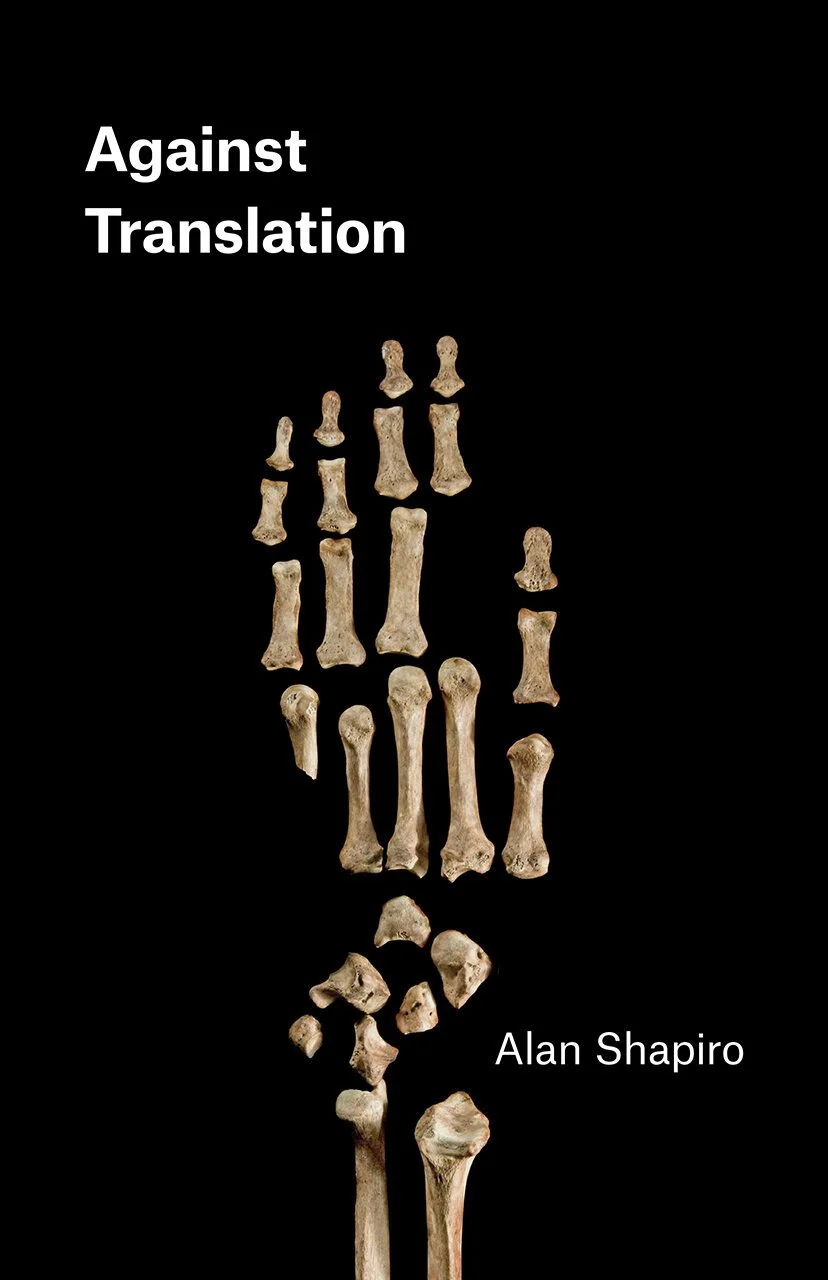

Alan Shapiro | Against Translation | Phoenix Poets/UChicago Press | 2019 | 96 Pages

When I tell you I love you, I am thinking, of course, not of what is lost in the saying of it, but rather what is gained. What loss of meaning occurs upon transmission of an idea is not often considered in the expressions of self, of which speech and language play a key role. In Against Translation, Alan Shapiro takes it upon himself to plainly present the occasions in which the intent of the communication is absent from its outcome—where what is lost becomes paramount to the investigations of self and others; and in doing so, centers not what is said, but rather what is unspoken.

Within, the book hosts a multitude of speakers, each with their own drastic textures, often taking risks in the placement of vantage point—that of a father with a potentially queer child, a husband visiting his wife in a nursing home, a cancer patient envisioning the life of her friends without her, one recursing through memory considering the suicide of a prison inmate, an ekphrasis of a neo-nazi march, and an autobiographical speaker, among others. Very frequently the shifting view-points land upon poignant narratives and thought-trails, but there are moments within the collection where the attempts fall short, as in “Justice”—whose speaker considers the suicide of a prisoner:

“…when I heard how

he had greased the floor with shampoo

before he hanged himself so when his legs

thrashed his feet would just keep slipping”

The poem itself is well crafted, with an intentionality among the line breaks reminiscent of a surgeon while being certain in their propulsion towards surprise with each jump, however, moments within read as “trauma porn” with its glorification of suffering. It is unclear regarding the relation between the speaker and inmate, and reads as one simply reimagining pain centralized on another’s being:

“it was as if I staged the suicide myself

in a godly fantasy of payback…”

The undertones the poem demonstrates are those of retribution and an attempt to implicate the inmate in deservance of this fate. The considerations verge on harsh, regardless of the suggestion that the inmate was guilty of murder. Yet, there is an important lesson to be learned about guilt from this poem, which echoes again in other poems throughout the collection. The message is this—gestures towards the ways in which shame effaces us. What this poem lacks in thoughtfulness and empathy, others in the collection make up for, overall demonstrating a listening and asking spirit, more intent on questions than presentation of answers masquerading as accepted wisdom. The collection meanders around the pitfalls certain speakers may carry in terms of stereotypes and offers unexpected moments of clear empathy that require a gentle spirit.

In the past Shapiro’s work has been regarded as narrative, often incorporating larger considerations in the poems’ placements within the collection. Where this one eschews a longer narrative, there are smaller recurring points of view within. The speakers are chosen carefully, their viewpoints acting as specific selections aiming to further the poems’ aboutness, many times acting as bystanders, an important poetry of witness. Within this vein, Shapiro will contemplate whiteness frequently, very much implicating the speakers and treading lightly over hazardous grounds. This is one of the many things the collection does well at a time when not many other white male poets have succeeded, one very fraught and unsuccessful example being Bob Hicok’s recent tirade on his “erasure.” Shapiro is cognizant and avoids overstepping his bounds when it comes to race in his poetics (from “Hurricanes”):

“…in a different kind of weather, the police on my

television screen, in black riot gear and standing shoulder to shoulder

perfectly still in a straight line, faced a crowd restlessly coming and

going in the streets…out of the maelstrom, as if both to hold it off

and to answer for it, I’m back inside that eye where all you can hear

is the laugh track, while outside in living color the windows implode”

The collection’s most moving moments are an extension of empathy towards people we may never be, almost an expansion of self into the places we are not. This comes through the poems’ attention towards utterance and who is given voice in the collection, as well as through contemplation of misunderstanding or presupposition. As a whole the collection acts as a reconsideration of the people we think we know, and everything which we purport to understand (from “Presposterous”):

“…makes me

wonder in the aftermath of

yet new carnage

if there isn’t

something of that nothing

we began as

even now inside us grown

so tired of the attempt

at waking

into something

that it wants to just

go back”

Among the many things this book can be to a reader, my favorite of them is that this book can be an opportunity to find ways to say I love you to strangers, and in doing so, teach yourself to look through another’s eyes, intent on discovering what they hear when you say it.

This review is part of the CRB x Barnhouse Series, which was created in partnership with Cleveland press and literary collective Barnhouse in order to better highlight recent poetry releases. Learn more about Barnhouse here.