Pere Ubu Understands America and I Don't

1. In the Summer of 2016

Everything was fucked up. "Unreal," if you want a more polite word. Topsy-turvy. Trump was inescapable, spewing hatred on the television, internet, and radio, and while a few of my friends here in Columbus spoke about his chances of winning in November with the bemused tone of a sedated NPR news host, certain that this, too, shall pass, most of us were freaking out. You could smell panic rising off the hot pavement on the corner of Hudson and High and fear in the cornfields north of 270 where yard signs implored us to Make America Great Again. Devoid of qualifications, Trump seemed like a mistake, or a prank. But he was also the logical endpoint of the past seventy years of capitalism, mass media, and neoliberalism: a Richard Nixon-Roy Cohn hybrid with Reaganite policies and Robin Leach's Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous taste; with Bill Clinton's sex drive and unerring belief in his own charm; with George W. Bush's goofy incompetence and tenuous grip on reality—all of it rolled into one human body with hippopotamus eyes. Casual treachery was in the air, poorly disguised as entertainment. I read the message on the back of an old postcard that summer: "In a world that really has been turned on its head, truth is a moment of falsehood."

That July, I finally heard Pere Ubu perform "Final Solution" live. It was at Ace of Cups, a rock club that used to be a bank and then a grotesque chach bar. Now it's the best live venue in the city, and the night before Independence Day, Pere Ubu was there, playing ordinary rock music.

A strange thing to say, I know. The orthodox descriptions of the Cleveland band have always been "art rock" or "experimental rock," i.e., avant-garde rock music composed of jarring structures, atonal melodies, bandleader David Thomas' loopy vocals, and, at times, the alien sonics of a Theremin. However, from where I was standing shoulder-to-shoulder with maybe three hundred other sweaty citizens in this hothouse, what struck me first was the understated manner with which Pere Ubu went about its work. Drummer Steven Mehlman, bassist Michele Temple, synths and Theremin player Robert Wheeler, and guitarist Gary Siperko took the stage first. Then Thomas climbed the steps assisted by a thick cane. Seated front and center in his customary bowler hat, eyeglasses, and red suspenders, he looked like the Stage Manager from an honest production of Our Town. The band crept into "Heart of Darkness," the B-side of its first single in 1975. The beat started heavy on the one, building, giving and taking, but there was nothing extreme put into the performance. The band just followed the song where it went, without histrionics. You could almost mistake them for any other band playing on a Sunday night.

Thomas' face was the only source of visual drama. His eyes fluttered. His head shook occasionally at something he heard in the music, as if the sound was forcing him to respond. Much thinner now than when people called him Crocus Behemoth, his presence was no less mammoth. When "On the Surface" followed "Heart of Darkness," its groovy keyboard intro transposed into a guitar lick, Thomas' voice took over the club. Greil Marcus wrote of the 1980 Pere Ubu song "Lonesome Cowboy Dave" that Thomas "[tried] on the nation as if it were a wardrobe," and this was the first time I could truly hear that ambition. In between songs, Thomas delivered what seemed like off-the-cuff monologues. One included a bit of music history. Seems that one night in Texas after a show, the Velvet Underground hopped in a hot rod ("they wouldn't be caught dead in their VW") and went to see Parliament. "When they came back to the motel after the show," said Thomas, "they wrote this song." Which was "Heaven," a Pere Ubu song.

For all of this theatricality and humor, there was still an interiority to Thomas' way of being on stage, far more centered and monkish than the gesticulating comedian you can see in their 1989 performance of "Breath" on David Sanborn's late-night music show, for example. Thomas is now the wise elder who hasn't stopped speaking in tongues. He carries on the tradition of the avant-garde, and at Ace of Cups it felt as though we'd gathered around the feet of the band to hear that story, especially since Pere Ubu's set, as it had throughout the seventeen-show Co-Ed Jail! tour, consisted entirely of songs from records and albums released between 1975 and 1982, the band's foundational years in Cleveland: a couple Rocket from the Tombs singles, The Modern Dance and Dub Housing, New Picnic Time, The Art of Walking, and Song of the Bailing Man. The show could have been an exercise in nostalgia, but Thomas' stoicism and the band's power and gravity avoided it by carrying the weight of the contradictions inherent in the notion of an avant-garde tradition.

Thomas would disagree with that. (Crocus Vehemently.) He's always preferred his own concoction: "avant-garage," a descriptor that rings true. Maybe it's actually more pretentious, but I can't help loving it. It's true that garage rock has always been the band's home. From its driveway they head out into free jazz, sea shanties, funk, musique concrète, pop, and then they pack up the van and head back to Cleveland. Sometimes in the same song. The key is usually the rhythm section. At Ace of Cups, the jarring song structures sometimes obscured how important Temple's bass bass lines were, but on "Modern Dance" and "Navvy" she drove them into my flabby guts. Mehlman, the youngest of the band, played the whole night with his head down, bulling forward with the right balance between articulation and force the early Pere Ubu songs need.

But none of this changes the fact that the audience sees and hears Pere Ubu as an avant-garde band: visionary, revolutionary, ahead of its time. Everybody in the Ace of Cups crowd knew Pere Ubu and David Thomas were Underground Legends, born from the moment when Rocket from the Tombs crawled up out of the dingy Lake Erie shoreline like frogmen and played a gig at the Viking Saloon in June 1974. The band lasted less than a year, but those months became mythical and the songs remained as proof—"Sonic Reducer," "Ain't It Fun," "Final Solution," "Life Stinks," "30 Seconds Over Tokyo"—via the Dead Boys and Pere Ubu. Everybody in the crowd knew those songs. In the cultish underground rock world, where the currency exchanged is the rarity of knowledge, Pere Ubu is rare enough. The night could have played out like we were all standing around a buffalo nickel. This form of cultural capital is how even avant-garage music can be crushed under the weight of a unique brand of nostalgia that Simon Reynolds in his book Retromania calls "record-collection rock." Applied there to bands in the 90s and 00s, it just as well applies to how an audience might hear a band like Pere Ubu today: as a cultural signifier instead of human beings. In fact, opener Lamont Thomas, a.k.a. Obnox, who's also from Cleveland and who played guitar like he was throwing sheet lighting, took a couple jabs at the "record collector" audience. A warning, really, that our knowledge could get in the way of our experience.

At the same time, Thomas positions Pere Ubu as a torch-bearing band of missionaries who adhere to an ideal, which is modernist avant-gardism par excellance. Thought before art. Theory guides making. The band's website, Ubu Projex, has a section for "Protocols." On the Facebook event page for the show, Thomas was quoted as saying, "We don't promote chaos, we preserve it." There is, in other words, an Idea. The thing is, this Idea has been forgotten. A chart on the band's website, "Schrodinger's Chart of Pop Music"—a winking allusion to the scientist Erwin Schrödinger and his thought-experiment concerning a cat and a box, though the band leaves off the umlaut, so for all we know it could be Frank Schrodinger, C.P.A.—explains Thomas' oft-quoted argument that Pere Ubu is "mainstream" music while pop stars like Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake are "experimental artists." According to the chart, Pere Ubu follows a "historical imperative, i.e., the Mainstream" which pursues greater "literacy," defined as "the ability, facility and will to pursue an accurate portrayal of the human condition with sound."

The more you think about that, the wider it spreads.

In any case, the band's mission, its stoicism, the record-collector audience's expectations, the specter of nostalgia, the craziness going on outside, and the intensity of the band's performance—all of this combined to create an interesting tension. Maybe a productive tension. You could sense during the show that the non-plussed way Thomas and his crew went about their business was a way of controlling that tension with the primary purpose of letting the music do what it could do.

Which is why the show seemed so normal. It was about the music.

As off-kilter and adventurous as the music was, it was presented so matter-of-factly that it came across as an enjoyable kind of work. Performance is work. It's normal for Pere Ubu. It's mainstream partly because it's their mainstream and we're invited. I don't think I had ever really understood Thomas' argument until I saw Robert Wheeler receding into the blips and keening whistles he drew from his homemade Theremin. How is it possible to take something so strange and make it so ordinary? Or is the question really how something so ordinary can be so strange? That's the dynamic Pere Ubu exploits.

Inside Ace of Cups, I found Pere Ubu comforting. Which was a strange reaction. Or at least, not the one I expected. Not even at their wildest, not even during the wacko spoken-word of "Rhapsody in Pink" or freeform horror matinee of "Petrified" could they match the freak show going on outside. And outside we had to go. After "Final Solution" and "West Side Story" and "Goodbye," we crept back into the world where Paul Manafort was gallivanting with pro-Russia Ukrainians and Trump Jr. may or may not have been coordinating with Julian Assange. (We didn't think this at the time, but we sorta did.) The world in which a maniac had killed forty-nine people in the Orlando gay nightclub Pulse and again Congress was doing not a goddamn thing. In fact, Left and Right were busy criticizing Representative John Lewis, a living icon of the Civil Rights movement, for staging a sit-in on the floor of the House in support of gun control legislation. (Leftists: "Too old-school!" Righties: "Too radical!") Was that world ordinary? Or was that world strange?

It was only after I left Ace of Cups that it seemed to me that Pere Ubu understood something about this country that I didn't, or couldn't, or didn't really want to.

I guess it was a couple weeks later that I saw on Twitter a photo of John Lewis smiling on a bench designed to look like the sprawling chest of Colonel Sanders, the mascot of Kentucky Fried Chicken. And then Steve Bannon was talking about how much he admired Darth Vader. And then, pussy grabbing. And Comey screwed up everything. And maybe there were Russians. And Trump won. Leonard Cohen checked out. Can't say as I blame him.

2. And Now in 2018

Everything is worse. Daily exposure to ordinary life feels like being run over by a clown car. You'd laugh if it wasn't so horrific and you'd cry if it wasn't so goddamn goofy.

For some reason which depends upon but extends beyond its music, Pere Ubu's show in 2016 has stayed with me. Its questions have stuck around. Why does it seem like Pere Ubu understands something about this country that I don't? The day after the show, I did what I do when I'm agitated: I wrote. About blackbirds and Wallace Stevens and wabi-sabi. About Trump and the working class and Cleveland, which is where I was raised. The words came out like a freight train stopped at a railroad crossing. I thought I'd forget all about it, but here I am. If you don't care about that journey, it's okay. The journey isn't the point.

"We don't promote chaos, we preserve it"—I keep coming back to that sentence. I love that sentence. But when I attach it to real life and what seems like never-ending chaos, I ask: Why? What's the point of preserving what is plentiful?

It seems to me that if I can understand that, I can know what Pere Ubu knows.

The public discourse is ample, ugly, thick, prickly, and swift. So much has already been said, so much is being said as I write this, and there's no way that you and I can keep up. The media theorist Douglas Rushkoff calls the effect of this pace and density "present shock," our persistently distracted now. Pere Ubu foretold it in 1977 with the concept of "Datapanik in the Year Zero," the name of an EP and described (later, I believe) by Thomas thusly: "[I]nformation will become a weapon to be used against us as notions of value and meaning are ridiculed in a storm of confetti." It reminds me of the way hi-def TVs fuzz out when they try to show real confetti storms. It's chaotic and unclear, mean and depressing. And heavily mediated. Rachel Maddow tells me every night that a lot is happening very quickly now and the phrase "Breaking News" is omnipresent at the bottom of the screen. This constant state of anticipation and fear—two goals of terrorism—produces numbness, even boredom, precisely because it's constant. And yet, the fact that it's so heavily mediated by television and the internet gives away that it is, in fact, not really chaotic. It isn't real anarchy. It's actually very orderly. Someone has to get paid.

In her recent book Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War, Hito Steyerl reflects on Giorgio Agamben's reading of "the Greek term stasis, which means both civil war and immutability…." Permanent conflict, she argues, is the general state of things. "A stagnant crisis is the point. It needs to be indefinite because it is an abundant source of profit: instability is a gold mine without bottom." There are multiple ways to express this stasis. The late theorist Mark Fisher called it "capitalist realism": "the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it." This is because the dominance of global capitalism is not merely an argument; it's the environment in which we live, a pervasive reality which affects everything, including art and music. In Capitalist Realism, Fisher draws from the French philosopher Alain Badiou, who has argued that the neoliberal global market presents itself as that in which everything is possible, everything is visible. Everything is already everything; there is no matter which does not already have a form. Nothing is impossible. Stasis again.

But there is a bottom: death. The end of a human life or lives, whether by bomb or cholesterol. The return of form to matter. And there are alternatives: socialism, communism, anarchy, fascism, or something else no one has yet thought of. They are hidden by the confetti storm of history (we change the channel) or the omniscience of neoliberal capitalism. And there are still invisible potentialities. They exist in real life, not in social concepts of order. What Steyerl, Fisher, and Badiou have diagnosed are the social fictions, the realisms, which affect and to some extent determine the real—and real lives. These fictions attempt to define the limits of the real; they are the barbed wire that encloses the chaos. Traditionally, order exists to prevent chaos from getting in, but the stagnant crises described by Steyerl, Fisher, and Badiou exist to keep chaos from getting out, so that it may be controlled and profitable.

This is what Pere Ubu understands about the United States that I don't, haven't, or still don't wish to understand. We are besieged and immobilized by order which enforces chaos inside the fence. Trump is only one manifestation, the figurehead, the icon: the Pere Ubu from Alfred Jarry's 1896 play Ubu Roi, a greedy, vulgar buffoon. Trump's purpose, whether he knows it or not, is to cast the shadow in which crafty men like Mitch McConnell, Paul Ryan, Jeff Sessions, and Steve Mnuchin may toil and prosper by promoting and structuring chaos.

The question then becomes, What is the source of the chaos that should be preserved?

Thinking about Pere Ubu, we might be tempted to answer, "Art," specifically avant-garde art and all it implies: anarchy, rebellion, art, collectivism, or even old-fashioned individualism. David Thomas rejects the avant-garde, though, on the basis (I'm guessing) that each of those qualities I've just listed have been easily absorbed into the social order as tolerated oppositions, e.g., "free-speech zones," and co-opted norms. The Orwells' 2013 pro-youth revolution song "Who Needs You" was used the following year to sell the iPad Air 2. It was catchy. Made me want to buy one. Then Apple discontinued the Air and replaced it with the iPad Pro, a reminder that youth is a study in obsolescence. Newness may destroy what precedes it, but today the modernist avant-garde "shock of the new" sells cars and phones.

Pere Ubu doesn't abandon all of the implications of the avant-garde, though. The question has always been, which avant-garde? In his book The Shape of Things to Come, Greil Marcus describes the band as "pre-punk, post-dada"; Jarry's play, which caused a riot at its only performance, is usually considered a dada herald. So we're on the trail of anarchists, and perhaps not so far from the avant-garde defined by Clement Greenberg in 1939 as a defense against kitsch, but Pere Ubu is neither a rejection of pop culture nor an ideological project in the political sense. Instead, the band's purpose is to join art with real life.

David Thomas once wrote, "Real life is the only worthwhile ambition for Art." Maybe you, like me, would respond today, "Really? This life? Art should strive to be like this shit?" An understandable reaction. However, read that statement in the context of the entire passage from "Chinese Whispers: The Making of Pere Ubu's Lady from Shanghai":

“The musician should be alone with his thoughts, uncertain but determined. Isolated. The goal should be to capture the unique and distinctive voice of the individual as he struggles to cobble Meaning together out of a soup of confusions, contradictions, hopes and fears, information and misinformation. Such is the nature of real life. Real life is the only worthwhile ambition for Art.”

In other words, art doesn't just represent the everyday, seemingly mundane aspects of real life. It's an attempt to think through it—and to do so through art. If this art is going to be honest, it has to be a thinking-through of the immovable blocks, the stagnant crises, the static forms and social fictions of culture and politics, and the noise and "soup of confusions" they create. That experience is real life. It's me staring at "Breaking News Breaking News Breaking News," but it's also me in traffic and listening to weird neighbors and fighting off the ghosts of old conversations and wondering what'll happen to me when I die. It's me after the Pere Ubu show. And it's what Pere Ubu puts into its music, dramatizing the storm of confetti in order to create the situation in which subjectivity works. In a winding, ambitious essay titled "Elitism for the People," the pseudonymous author Entrippy notes all of this, suggesting that the "Datapanik in the Year Zero" concept of information overload forced the band's Stockhausen-ian hand. Early albums like Dub Housing are rife with sonic confusion and anxiety, dub as method, not a genre. Voices shout at one another across a crowd. But this environment has no center except the attempt to find one.

Pere Ubu's music is an argument that art must choose real life or the social fictions given to us: experience or knowledge, ontology or ideology, real or realism, chaos or order. I would guess that the moment when pop music began conforming to social fictions instead of creating them is the precise point on "Schrodinger's Chart of Pop Music" when pop diverged from its historical imperative. It was no longer interested in accurately portraying the chaos of the human condition. Instead, it simply reiterated the orderliness of social thought. For Pere Ubu, music shouldn't be the result of thought, but rather thought in action; not wisdom arrived upon, but the performance of thought's arrival.

This effort to align art with life finds an unlikely predecessor in the avant-garde: the Russian painter Kazimir Malevich. If the Dadaists wanted to turn life into art, Malevich wanted to turn art into life. Both were hell-bent for leather to disfigure and bury the art of the past, though, and in a 1919 essay, Malevich argued that pre-revolutionary art and its museums should be allowed to die, writing, "In burning a corpse we obtain one gram of powder." But as the art historian and philosopher Boris Groys argues in In the Flow, Malevich was trying to place art on the same vulnerable footing as life, to show that it was susceptible to the destructive power of time. Malevich's Suprematist paintings like Black Square, Airplane Flying, White on White, and Black Cross reduced art to its most basic forms, frail and geometrical shapes that suggested the aftermath of an apocalypse and the rebirth of art. When Groys sums up Malevich's position, that "[t]he fate of art cannot be different from the fate of every other thing," I hear simply another way of saying,"Real life is the only worthwhile ambition for Art."

Like Pere Ubu, Malevich sided with life but not the preformed socially-mandated ideals which attempted to corral life's chaos. His response to the pragmatism of the Russian Constructivists actually sheds some light on Pere Ubu. Groys describes it as a "dialectics of imperfection." The painter argued that ideology, power, and the social realisms which they enforce aim for perfection. Purity. Order. Stasis. Essentially, the end of time—which is either utopian or apocalyptic, depending on your point of view. Or a lie. (How often do concepts and ideals attempt to hide the operation of time in real life, to obscure the degradation, slow suffering, and snuffing out of human life, for the sake of power?) Malevich believed such projects were destined to fail, and as Groys puts it, that "[p]riests and engineers…cannot accept failure at their true fate" but "artists can." Art on the side of life meant a recognition and embodiment of life's susceptibility to imperfection and time's passing—to the disease of living, to the truth that we are "infected by the bacilli of change, illness, and death," says Groys. Thus, "[a]rtists need to modify the immune system of their art in order to incorporate new aesthetic bacilli, to survive them and find a new inner balance, a new definition of health."

Isn't this what Pere Ubu has always done? The frenzied clang of real life in their music doesn't deny chaos, it ingests chaos in order to keep going, to keep responding to real life. Early songs like "Street Waves," "Non-Alignment Pact," "Modern Dance," and "30 Seconds Over Tokyo" work as recognizable rock tunes infected by social pandemonium: alarms, the din of public spaces, the shrieking of machinery, distress signals, guitars being sawed in half, a bank of televisions tuned to different channels and turned up loud. Songs like "Caligari's Mirror" and "Dub Housing" sound like the night after a pandemic has finished its business. Pere Ubu's destructiveness isn't as absolute as Malevich's Suprematist paintings. It's more reconstructive: smash-and-grab first, then a rearranging. But all of it serves this purpose of performing consciousness in modernity, including what Groys describes as the "modernist inheritance" of "the will to reveal the Other within oneself," which is the vulnerability and frailty but also the ability to adapt which Malevich championed, a "strategy of self-exclusion—of presenting oneself as infected and infectious, as being the embodiment of the dangerous or the intolerant." Rock 'n' roll is no stranger to this inheritance. Read this portion of In the Flow and tell me it isn't a punk manifesto. I mean, The Germs, right? Pere Ubu isn't as absolute, not always, but the band's firmness of purpose and stoic performance style communicated to me that night at Ace of Cups that the only thing which matters is that life and art continue. "It is precisely this self-infection by art that must go on," writes Groys, "if we don't want to let the bacilli of art die."

Infected, art becomes infectious. It might inspire chaos, which in turn might break through stasis. By its transmission people might produce themselves not according to the final solution of an ideology but according to a process and method by which they can imagine something different: change, alternatives, the invisible, the inaudible. The historical imperative followed by Pere Ubu has no endpoint, no political goal or ideological utopia, just as Malevich rejected such endings. Potential is the chaos that needs to be preserved.

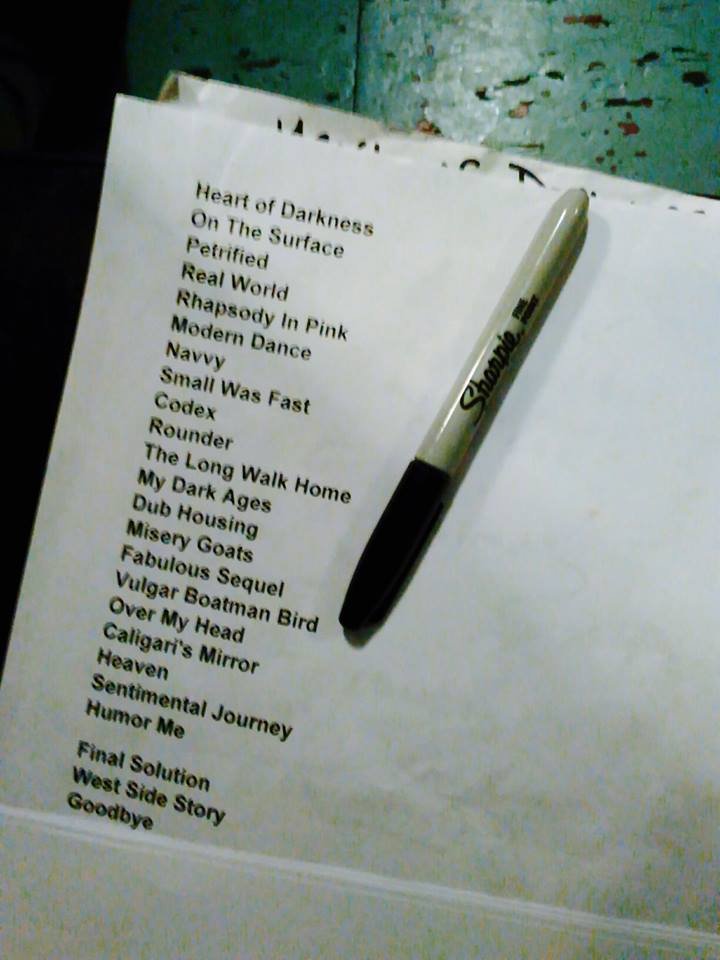

*Image: Pere Ubu set-list; courtesy of Jah Nada

This review is part of our Music and Society series, where we analyze music from a lens traditionally reserved for literature, fine art, or film.