Rubbing Love from Silences: On Silvina López Medin's "Poem That Never Ends"

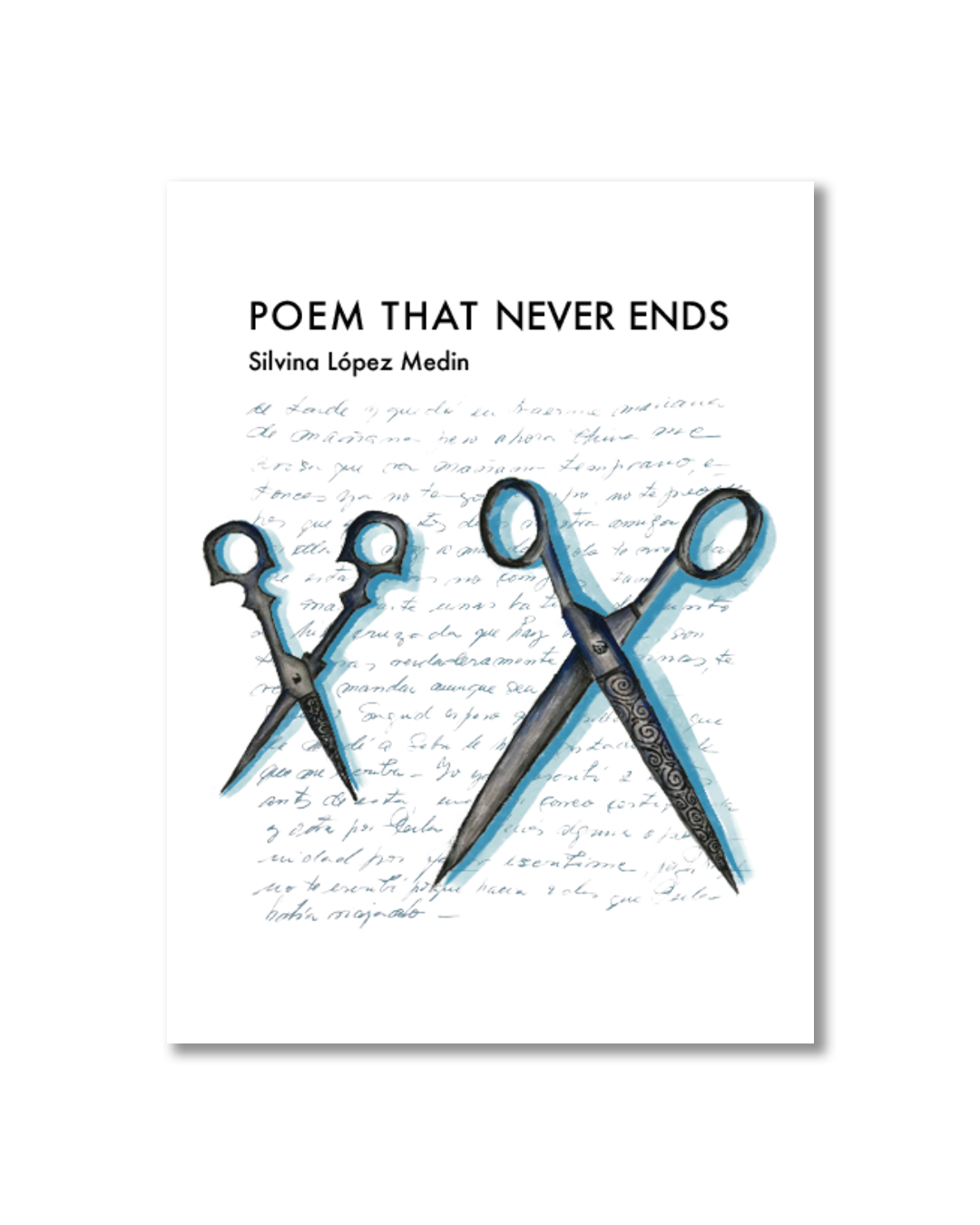

Silvina López Medin | Poem That Never Ends | Essay Press | 2021 | 85 Pages

*

Learning to sew, I discovered the choice of fabric determines what can be created from it; the textures and thread pattern of the materials determine the stitch. Silvina López Medin's Poem That Never Ends, her first collection written in English rather than in her native Spanish, brought the formal considerations of sewing to mind. Through Medin's use of fragmented materials, the connection to sewing complicates the location of edges.

Ching-In Chen, who selected this book as the winner of 2019 Bethell Book Contest, calls it “a story about linearity of edge,” though it feels closer to selvedge, which is the self-finished edge of a piece of fabric that prevents it from unraveling or fraying. A selvedge needs no hem or bias tape, no additional finishing work to prevent the fabric from coming apart. In this book, Medin works from the existing materials of family and history, chronicling an intimacy of phrases and edges, exposing the seams in silence, while also creating one “piece” composed from stitched fragments.

“In this piece, language is a necessary distance,” she writes, referring to both the book and the fragment. Continuing the cinematic and visual palettes of Excursion, her 2019 chapbook, Medin explores ontological division as its own modality, rather than a rupture which needs suturing. The poem never ends because the edge is always expectant, always waiting for something to be added to it. The scar will not heal. It will grow a new skin, a soft skin nourished by the climate, a skin marked in new words which the locals can understand. But the old words are not disappeared by the new ones. The scar is a story of seams.

*

Writing from Brooklyn, where she lives with her sons, Medin dedicates the book to her mother and sons. She begins by addressing her mother in Argentina. “The Sound of Blinds Being Pulled Up is the First Sound,” a prose poem narrated in second-person, explains the work that “mother” will do as lineage:

You cross out the word grandmother, you'll say your mother's mother. You'd rather have the word repeated—mother—build a chain with no missing ring.

The speaker lays out the process, which mimics cutting fabrics for patterns prior to stitching the parts together:

To separate the cloth just into pieces. This is not your daughter, this is not you. And yet, you are a mother, she's your mother's mother. You're pulling.

Abandonment haunts the lyrical and material text. Her mother's mother abandoned her mother for three years, from ages three to six, and Medin considers this action, this absence of a mother in her own mother's formative years, across the text, making use of diary forms in order to reflect on the intersection with her own life. In “Brooklyn, September 6, 2018,” the speaker reveals how she will expand time to accommodate the missing, the absent, the presence in the present. Remembered voices exist in dialogue with the text, as in “Brooklyn, October 20, Later”:

I look again at the letter from 1980. There my mother's mother says, “Tell Silvina to write to me.” I was barely 4, I couldn't write at all. I wonder if the voice I hear when I'm struggling is an echo of that voice: tell Silvina to write.

In bolding certain words, Medin alters the visual field but also the audible one: the bolded words sound louder than others. This bolding-sound operates at two levels: a symbolic one, which highlights the deafness on her maternal side, and a scriptural one, which posits the narrator as the amanuensis, recording words. The weighted words are critical to the final poem, constructed from these raised-stitch words.

*

Because distance demands its own time, this book fashions a temporality that limns the gaps between space, language, and silence. Rejecting assimilationist demands to stay alienated from her origins, Medin seeks an inhabitable, unfinished temporality, a whole fragment, a poem that never ends, an ongoing dialogue with her mother and history.

The tension between preservation and restoration emerges in the book’s letters and epistolary forms. Medin’s maternal grandmother wrote 126 letters to her mother, but only two of these letters remain, both of which center her work as a seamstress. Access to these letters is complicated by their destruction—Medin's mother ripped all the other letters to shreds after reading them—and the poet revisits this destruction in a visual erasure, an image at the beginning of the book which includes small wound-shaped cuts from letters (see below).

Medin texts her mother questions to learn more about her family history, but her mother skips four of them. “What's past is past,” the mother says. “What's past” is “a piece of paper inside a closed fist.” But the poet rejects this division of time, choosing to invoke “past, present,” the time signature of the photograph.

The page evokes a three-dimensional field through its inclusion of photos, erasures, and images of gallery exhibitions; the book emerges from the unerased—the only two letters her mother didn’t destroy. In dating some pieces as diary entries, and specifying where they were written, Medin creates tension between title (which is temporally determinate) and content (which speaks to indeterminacy and hunger for wholeness). “October 29” builds on the injunction, “You will forget,” by addressing it, by speaking to forgetting. “You will forget that this is you.”

Many of the images are photos of photos, taken by her mother and texted to her over the phone, and the paratext of family photos is approached with reference to Roland Barthes' punctum. “What is the wound, Mother, in this photograph?” Medin asks of overlapping gazes in a family photograph. Again: “The photograph of a photograph. Like a memory retold. Is that the wound?”

“She is a present tense person, my mother,” the poet explains in “Brooklyn, November 15, 2018”, in which we learn her mother is in Paraguay, visiting her brother, one of four siblings. A relative says the mother's mother did not keep a journal: “Four children, a husband, all her work.” Women who work “don't have time” to keep a journal, the implication being that Medin’s own life is characterized by leisure, the privilege of the artist. One feels the pain in this implication, and in the mother’s refusal to hold the past in words, thus forbidding anyone from visiting it, or growing inside it.

*

In a recent interview with JD Pluecker, Medin spoke of the inability to see our parents outside the roles they are playing, and how this limited gaze haunts mothering. Motherhood, itself, is a language Medin longs to speak with her mother, to distill the roles that motherhood gives us, the blueprints, the patterns, the challenge of creating a dress outside inherited patterns. In “Brooklyn, November 17, 2018,” the speaker meets with an “education specialist” who asks her to describe her son, and the poem ends in proximity:

How can I describe him, my son. I start, I stumble, I bump into the “He”, say “I”.

To speak of the son is to speak for him; it is to confuse the distance between the he of expectation and the I of being. Again, we see the mother, trying to find the boundary between her body and that of the child in “Brooklyn, November 5, 2018”, where her son calls for mom, not recognizing her presence in the dark room. The prose block breaks into lineated poetry:

to become

almost transparent

the kind of paper you use

only on one side

lest the words tangle

with the back of the words behind

I felt pulled into a relationship between these mother-daughter mediums, the interplay of forms, the writer's paper and seamstress' fabric, the motion of the mother flying between lands—Paraguay to Argentina and back—and the daughter tracking these motions into places left before, creating a map from the spaces and silences between them. The way we define memory followed me through Medin's book, meeting near an end-note in Michel de Certeau's The Practice of Everyday Life, in which he suggests memory “designates a presence to the plurality of times and is thus not limited to the past.” The pull of this plurality made me think of fragmentation as a formal technique in which dislocation is part of inheritance. [Medin’s inclusion of a poem in her native Portugese further invites the reader into the intimate dislocations of such inheritance and communion. “I won’t translate it,” Medin writes, “so you can at least read this, Mother.”]

Maybe the map is a house made of seams which include mother-words and mother-tongues. Like Annie Ernaux, reflecting on the manual labor of her mother's life, and its distance from her intellectual career, Medin honors her mother's labor in how the text is structured. Medin's mother is a seamstress. Her mother's mother was also a seamstress. Her illustrated dress designs form part of the paratext.

In “Brooklyn, April 21, 2019,” which convenes near Korean artist Du Ho Suh's “rubbing/loving”, Medin says “clothing is the most intimate inhabitable space that you can actually carry”. There is resonance between Do Ho Suh's exhibits which translate “architecture into fabric” and a gift from Medin's mother:

…and then one day she gave me a present I had longed for and I still keep: a tent, a stitched version of a house.

The ekphrastic object is absorbed into paratext: a photograph of Medin and her sons visiting “The Perfect Home II,” Do Ho Suh's life-sized replica of his former New York apartment, made by hand, stitched from fabric. In the blurry grayscale photo, the wall of fabric is translucent—and Medin sees her son through it. This is the final image before the concluding poem, “Coda,” which brings together the bolded text to create a single, long poem that revolves around the word mama, or the forms this word takes in varying invocations. It concludes the book without concluding the poem, for the poem, the dance between mothers and daughters, cannot end. This final poem, with its bolded repetitions, is the house that Medin builds from stitches. The loss of hearing that would affect her mother and her mother's mother exists at the level of the text in informal ways including use of visuals, repetition, reorganization, interrogation, and what she has called writing “a porous, restless gesture towards what's never fully grasped.”

We see each other through loose seams, the poet implies, and we hear each other by assembling the salient into a story, which must be incomplete, by nature. Mama carries so much, its resonances include “the reminisces of bodies lodged in ordinary language and marking its path, like white pebbles dropped through the forest of signs”. It is the poetry of what Michel de Certeau called “quoted fragments” that persists, adding the energy of incompleteness, an intimacy that gestures towards continuance and possibility so that the text, itself, evinces the “resonances” of a touched body—“enunciative gaps in a syntagmatic organization of statements.” When Medin speaks of her motherhood, and all our motherhoods, “lost in a dominant nameless motherhood,” I think of the dress we inherit as mothers, the house we step into, the fabric walls that hold us. Sometimes, we are given the opportunity to see one another through them.