Talking to God Again: An Interview with Noor Hindi

Noor Hindi | Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow. | Haymarket Books | 2022 | 80 Pages

Noor Hindi’s debut poetry collection Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow. is, in her own words, a book that covers a lot of terrain: Palestine, family, queerness, grief, the many intersections of these territories and more. Beyond thematic terrain though, this is a book that seeks joy. True joy. Not out of hopeful naivete, but from a place of deep, lived grief. It’s been my pleasure to be close friends with Noor for a few years now, and I was honored to sit down with her recently to discuss this brilliant debut.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Delilah McCrea: This book opens with an epigraph, “For those on the outside of the door. Let this book be an invitation, as prayer, as love. Come in.” This quote reminds me of conversations you and I would have in our MFA program about our respective experiences writing as poets of different marginalized identities and the question of who our work is and isn’t for. I remember in one conversation you brought up the question of whether or not to translate Arabic words and phrases in your poems, and you mentioned another Arab writer bringing to your attention the idea of not wanting to unintentionally exclude members of the diaspora who may read your book that, for reasons outside of their control, couldn’t read Arabic. So my question is, in this book and all your work, how do you balance the desire to make it as accessible as possible to those whom you wrote it for, with the desire not to invite in members of the oppressive class(es) who would seek to turn not only your work, but your very being, into an object for their consumption?

Noor Hindi: I think, first of all, it's important to talk about the fact that the book has some limitations in terms of audience because I grew up very lonely—very separated from an Arab community and most importantly, very separated from a queer Arab community. The people that made up my mentors and instructors as I was emerging were predominantly white women. So naturally the voice in my head—the voice of the editor in my head—was often a white person. That being said, I did a lot of work during my MFA to find a queer Arab community and an Arab community who I was speaking to and for. For example, I made a lot of connections through RAWI (Radius of Arab American Writers), which was super integral to just having people in my life that were reading my work, that were studying my work, that were interrogating my work and interrogating me. I think in some ways the book is limited in that I don't think I was always speaking to my Arab community in every poem. But I think the poems have still resonated with that community, and with the community I hope to continue being a part of. It feels like moving to Dearborn, which is like the Arab capital of the Midwest, has been really important. It was really cool to have a book launch here and have a room full of queer Arab women in the audience who the poems really spoke to. That was a very wild experience to be able to launch that book in that space. You were there during that reading, and I feel like I left my body during that reading.

[Both laugh.]

I was like, “Holy shit!” I've been working from this place of silence and marginalization, and seeking connection my whole life and wrote this book out of so much loneliness and sadness, and then launching it in the world to an audience of these women who I felt really connected to in that moment when I was reading those poems and who were really feeling those poems. And that was so integral to the experience of writing the book. So, I think ultimately I wrote to my community through writing to myself, thinking about the life-saving poems and work that I wish I'd had growing up. Especially around 18 to 24, I wish I'd had somebody who was writing about hymens and queer Arabness and just saying that word. There was a long time that I didn't think queer Arabs existed, right? I really thought I was the only one, and I wasn't.

DM: We were in the same MFA program and obviously we have different experiences, but similarly I had a lot of mentors and editors who were white women and weren't trans. What I feel I get from your answer that I also believe is: as long as you're writing honestly about your experience—especially as a marginalized poet—because you're writing for yourself, it will resonate with the people you are ultimately wanting to write for. The people who have the same experiences as you and who wanted the same poems that you maybe weren't able to find.

NH: Yeah. And desperately seek. I think it is, in a lot of ways, life-saving work for so many of us that feel like we're walking through the world without a sense of being seen or known or heard.

But I would say every MFA program is broken. The system of an MFA is broken. Like many systems, it's built for cis straight white men. I think there's some work that needs to be done in that. But what I took from the MFA that I hope anyone who’s marginalized takes is that you get a few years of time to focus on your work and to focus on reading. That’s what’s important. And if that is the only thing that you get, well, that's pretty great, right? Just the time and the energy afforded to you. Find the community that you're writing for outside of it. Do the work of reaching out to people who are part of your specific community, because your MFA program probably is not going to have it.

DM: Hopefully you'll at least be exposed to writing and books by people that might be members of your community, and then that'll be able to start you down a path of finding more writers who are in your community.

NH: The best thing to do, I think, is read. Find somebody from the community you're writing for, find their book. Look at the places they've published, read those journals, read those other artists that they've mentioned. That's how you find your people.

I do think on some level you will benefit from having people read your work critically as well. We were both very lucky to have people on our committees that were supportive in all of the ways that they could be, and also knew where they were limited. That's really important too.

DM: I know from personal experience of being your friend while you were writing this book that it took you a while to land on a title. I really love the title you went with, even if it wasn’t my suggestion, because it highlights something in your work that I find very resonant, which is your tendency toward direct address and often address of the divine. Do you think of your poems as prayers, and/or direct addresses? And if so, who are the different figures you tend to be addressing?

NH: I love this question so much. I feel like I am often talking to God to some extent.

After my cousin died—it was such a surprising and depressing and shocking tragedy and I couldn't and still can't understand why it happened—for a couple years, I'd stopped believing in any sort of organized religion. I stopped believing in a God that existed. And the way that I found God again, is that I would journal. I would find myself coming back to speaking to God. The notebook was the only place where I felt that I connected with this being, and connected to my cousin, and connected to myself and my body. Those were really, really powerful moments that brought me back to believing in some sort of God. So yeah, I do find myself naturally talking to a god in my work. Talking to grief, to death, talking to the color yellow, which has become a symbol of death and hope and joy and grief in my life. I love the epistolary poem for that reason that you're in direct communication with this person or this thing. It feels like a private conversation, even though it is public and it's sort of communal just as you have this connection to a reader. It feels very personal. And that's the thing that I really, really love about poetry.

DM: I love something you said in that answer. That when you were journaling and finding yourself talking to God—when you weren't really believing in one anymore—you said specifically, you found that the notebook was the only place where you felt connected to God, and to your cousin, and to your own body. And that almost sums up the title of your book: Dear God, dear bones (your body) and dear yellow.

NH: That's true. Before the pandemic, you and I would go to readings and that felt sort of like a religious ceremony.

DM: Yeah, it was like a religious service.

NH: It felt like going to service every Friday or whatever. There was so much quietness in the room and beauty and silence and connectedness. Some of the quietest moments of my life have been listening to a poet recite their words around people. A very packed room of people where you're elbow to elbow with somebody and listening. I think writing is such a spiritual act, and it’s such an act of bravery.

DM: The experience of going to the reading, it really highlights what you're saying about loving the epistolary poem, where it becomes this simultaneously private and public and personal thing. Where like the reader has published the poems most of the time and is sharing them in a public space, but it's a very intimate kind of sharing. Each person in the audience feels like they're having this individual conversation with the reader.

NH: And each person picks up on different things. So many poems have been changed, for me, by hearing the voice of the poet. When you hear somebody reading it and you listen to the words that they are hanging onto and how they present the poem. I think it completely makes the life of the poem. Poetry is a shared experience. It should be a shared experience, a communal experience. It's one that brings us together.

DM: I’m a big fan of the structure of this book. I think there’s a lot of poetry happening in the flow and movement between individual pieces and sections, both intentional and serendipitous. For instance, I love when just looking at the table of contents how the placement of each Breaking [News] poem creates what feels like literal and poetic headlines: Breaking [News]: Palestine, Breaking [News]: A Day, A Life: When A Medic Was Killed in Gaza Was It and Accident, Breaking [News]: I Buried My Brother Last Winter, Breaking [News]: All My Plants Are Dead. Can you talk a bit about the structure of this book? How did you decide on sections, and how to order the poems within those sections and order the sections within the book?

NH: That is so funny. I never noticed that about the book. I'm still learning parts of the book.

Ordering the book and sequencing poems was maybe the most difficult part of this process. The collection covers so many different topics and subjects and voices and themes and questions and arguments. It was really hard actually to house it all under one roof. But I also felt adamantly that I wanted a speaker that was a full speaker. I wanted a full book that covered a lot of different terrain. I didn't just want a queer book, or a Palestine book, or a diaspora book. I wanted all those different identities to be in the book. I think that often a first book ends up being a culmination of your life and very personal and very confessional. That happens because you're young and you kind of have to get all that shit out first before you're ready to write your second book about something outside of you maybe.

I wanted all parts of me recognized and seen. So ordering it was hell. It's very much a Gemini baby book. It's very ADHD. It's a little disorganized, it's a little chaotic and I love it for that reason. That being said, I think that the first section of the book establishes maybe a little bit of the confessional, a little bit of that humor, a little bit of the politics. The second section hones in on immigration and family a bit more. Then the third section goes into a lot of womanhood and coming of age and queer womanhood specifically. It covers a lot of terrain in that way.

I remember Caryl Pagel, my MFA thesis advisor, clustering the poems into little groups, and that helped me because I think I just ended up spreading out all of the poems in a living room and I was very lost, and she was able to like hone it. If you're sequencing your book, get somebody who's not you to look at it.

DM: Have Caryl Pagel, specifically, look at it. [Both laugh.] She also did that for me with my manuscript and it was super helpful.

NH: She saw connections when I was so close to the poems that I couldn't even see them anymore. Which happens. So, yeah. Get feedback from somebody else.

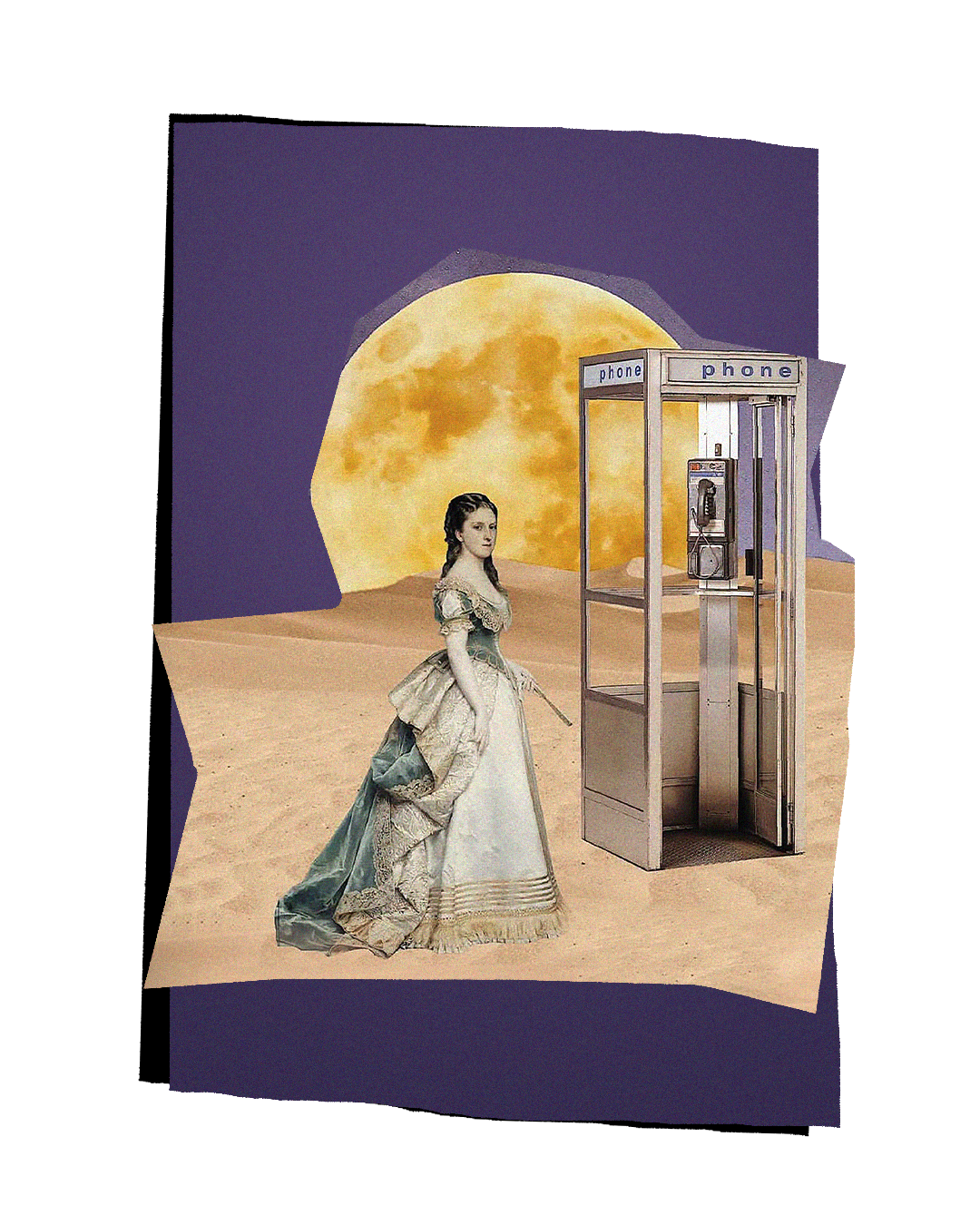

DM: Can you tell us a bit about the cover art? It feels very connected to the poem “I call my mother from the moon.” How did you come across the artist and was this piece made specifically for your book?

NH: This is so funny and I love this. So, the artist's name is Arwa Alshami. She's on Instagram as arwas.space and she creates these really interesting collages of space and time. The piece was not made specifically for the cover. It was altered for the cover. I really wanted an Arab woman to design the cover, and I was going through her Instagram one day. My cousin sent me Arwa’s page and I found this piece of this woman holding a fan standing somewhere in space with the moon behind her at a telephone pole, and I was like, “Holy shit, this is my cover!” She altered the photo a little bit. She made the moon more yellow. I love the cover because the woman is in a wedding dress—and all of the symbolism of weddings and the institution of marriage that represents. Especially the pressures for us Arab women to get married, to believe that we are to move out of our father's house into our husband's house and all of the problematic ideology that comes with that. I love that she's standing at a phone booth as if to relay this message. And in the poem, “I call my mother from the moon,” I'm talking to my mom from the moon on the phone. I love the like other-worldly element of the cover. Because I think there's a bit of strangeness in this book, too. So it was just really perfect and it was really, really cool that I found that piece and that Arwa agreed to let me use it.

DM: Last Question. You already answered this a little bit, but I still think it’s a good note to end on: What does the color yellow mean to you?

Noor Hindi: The color yellow is joy, is grief, is a persistence to continue, is community, is love, is friendship, is heartbreak. I think this color is so powerful because it embodies so much of these themes to me. Specifically, after my cousin Zina died, I got really obsessed with sunflowers. I don't know why. I think it's the sheer fact of them opening up to the sunlight every day. At night they're sort of looking downwards and like limping and then the way that they just…

[Noor looks up.]

…to the sky in the morning, I think is so beautiful. I remember my aunt asking me, “Do you love sunflowers because Zina loved sunflowers?” And I didn't even know that she did. In that way it felt as though they'd sort of been following me around. It only increased my love of them and my love of the color yellow. A lot of my life has been feeling that darkness and aloneness, and then desiring to just open up and see sunlight again and beauty and friendship and community. I think that, you know, you and I both have felt that; moving here and finding the love of just people around us and finding a queer community and feeling seen. And I feel really, really grateful for that.